The History of Tourmaline

The History of Tourmalines

The philosopher Theophrastus (371-287 BC) wrote that lyngourion, probably the mineral tourmaline, had the property of attracting straws and bits of wood. This would fit well with tourmaline’s pyroelectric properties. The problem is that until the 18th century tourmaline was often misidentified, so even though it is known to have been used for at least 2000 years, it has rarely been clearly identified and described as tourmaline. One of the oldest found tourmalines is from the 4th century BC – it shows an intaglio engraving of Alexander the Great in a tourmaline.

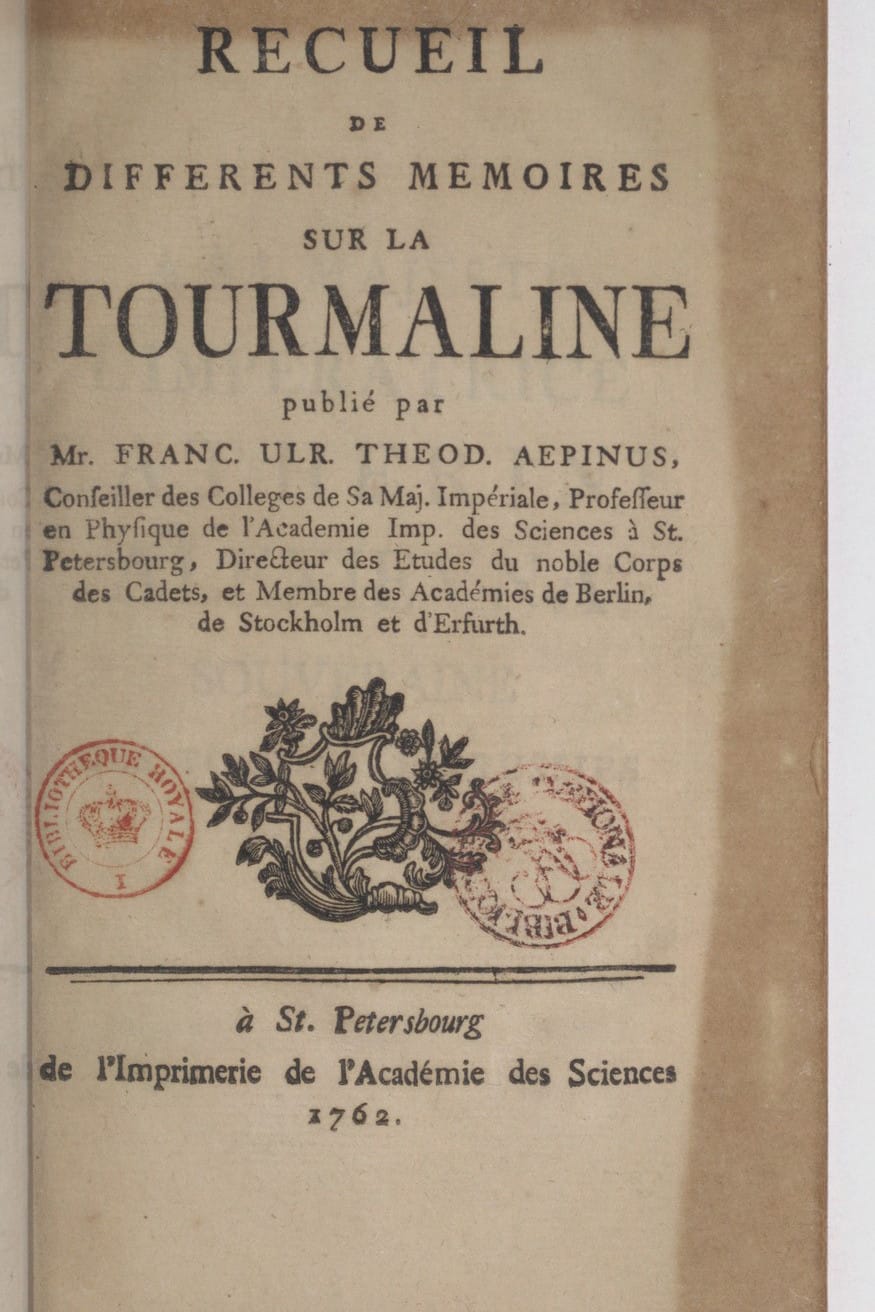

Later, in the early 1700s, Dutch traders (mostly the Dutch East India Company) imported many products from Sri Lanka, including gemstones. This is when tourmaline was first properly researched and characterized, largely because of the fascination people had with its pyroelectric effects. Numerous books were written about the gem, such as the 1762 compendium on tourmaline written by Franc Aepinus in honor of Catherine the Great.

One of the world’s oldest tourmalines: an intaglio in the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford, UK). Photo: Charles Evans (Gem-A).

1762 compendium on tourmaline written by Franc Aepinus.

However, tourmaline’s true potential as a gemstone was not fully realized until the 19th century, when new sources were discovered and more advanced cutting and polishing techniques were developed. The first tourmalines were mostly dark green in color, but, during this century, new mines were discovered in Brazil and California that produced a greater variety of colors, such as pink, red, yellow, blue and other hues. Thanks to the efforts of George Frederick Kunz (Tiffany’s chief gem expert), tourmalines gained popularity as an American gemstone.

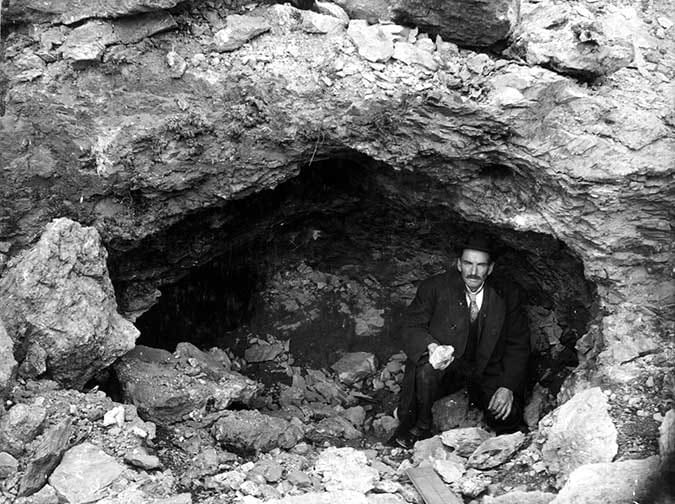

Mineral dealer Loren B. Merrill in 1911 in Mount Mica mine’s largest pocket (Maine, USA). Photo: USGS.

At the turn of the 20th century, demand for tourmaline soared as it was in great demand from the Dowager Empress Tz’u Hsi, who ruled China from 1860 to 1908. Although pink tourmaline was appreciated in China before her reign, her love of carved pink tourmaline meant she bought up the annual production of certain Californian tourmaline mines. When the Qing dynasty came to end in 1912, the US tourmaline industry was heavily impacted.

In this portrait of Empress Dowager Tz’u-Hsi (Cixi), it appears that a large pink tourmaline, along with a number of pearls, adorns her headdress. Source: Chinese School/Bridgeman Art Library/Getty.

A pink tourmaline ‘Peach and Bats’ pendant, late Qing dynasty; 1 1/8 in. (2.9 cm.) diam. Sold by Christie’s Hong Kong in 2014 for HKD 350,000. Photo: Christie’s.

In the late 1980s, a new type of tourmaline was discovered by Hector D. Barbosa in his pegmatite mine near Sao José da Batalha in the State of Paraíba, Brazil. This copper-bearing material can exhibit a vibrant blue to green color, and became known as Paraíba tourmaline; it is considered today one of the most rare and valuable varieties of tourmaline. Similar material would later be discovered in Mozambique and Nigeria. This variety of tourmaline has taken the modern jewelry world by storm, famed for its unique and beautiful vibrant blue to green colors.

A pair of Brazilian Paraíba tourmaline and diamond pendent earrings, of 2.59 ct and 2.32 ct respectively. Sold for US$ 406,000 at Sotheby’s in Hong Kong in October 2020.

Brazilian Paraíba tourmaline and diamond pendent earrings, of 2.59 ct and 2.32 ct respectively. Photo: Sotheby’s.

Famous and Record-Breaking Tourmalines

Swedish King Gustav III gave this tourmaline as a gift to Catherine The Great during his visit to St. Petersburg in 1777. It can today be found in the Kremlin’s Diamond Fund collection. The “Caesar’s Ruby” is a historical jewel that eventually turned out not to be a ruby at all, but instead a rubellite tourmaline, after it was examined by the mineralogist Aleksandr Evgenevich Fersman (1883-1945) while he was overseeing an inventory of the Russian crown jewels in 1922.

‘Caesar‘s ruby’: a 16th century carved tourmaline, reportedly from Burma. Photo: Diamond Fund of Russia, Gokhran.

The Crown of Saint Wenceslas, in Prague (1346). This was originally thought to have a central ruby but the stone was found to be in fact a red tourmaline. The other red stones are spinel.

The Crown of Saint Wenceslas, in Prague (1346). Photo: Wolfgang Sauber.

A multi-gem & diamond ‘Hedges and Rows’ necklace: J. Schlumberger and Tiffany & Co. – sold in December 2015 for USD $950,000 at Christie’s New York.

‘Hedges and Rows’ necklace: J. Schlumberger and Tiffany & Co. Photo: Christie’s.

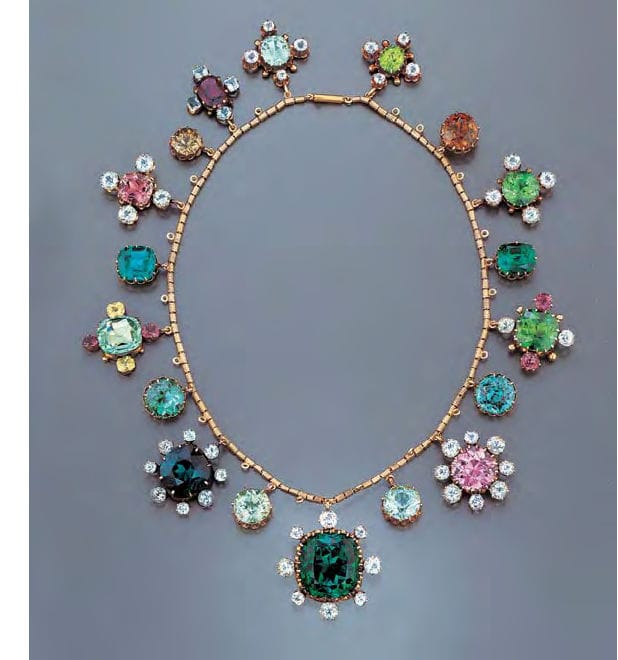

The Hamlin Necklace (at the Harvard Mineral Museum) was designed and created during the 1890s. Eighteen removable pendants with gems of varying colors, primarily tourmaline from Mount Mica, Maine, are attached to simple gold chain. In total, the seventy gemstones total 228.12 ct in weight and range in size from roughly three to thirty-four carats.

The Hamlin Necklace has seventy gemstones total 228.12 ct in weight. Photo: Tino Hammid.

A pair of heated Paraíba tourmalines from Brazil (7.46 and 6.81 ct) set in ear pendants, sold for 2.77 million US$ at Christie’s Hong Kong, May 2018.

Paraíba tourmalines from Brazil (7.46 and 6.81 ct) set in ear pendants. Photo: Christie’s.

A very rare carved green and pink tourmaline Imperial snuff bottle, palace workshops, 1760-1799. Sold in March 2013 for USD 171,750 at Christie’s New York.

Carved green and pink tourmaline Imperial snuff bottle. Photo: Christie’s.

A 21.63 carat Mozambique tourmaline set in a ring by Boodles. This stone was tested by SSEF and it is currently not possible to determine if the tourmaline has been heated or not. The color is, however, considered stable. It sold for $534,290 at Sotheby’s Geneva in May 2022.

21.63 carat Mozambique tourmaline set in a ring by Boodles. Photo: Sotheby’s.

Source: Swiss Gemmological Institute (SSEF).