Responsibly Closing Diamond Mines

Life After Diamonds: The Closure of a Mine

How exhausted diamond mines are transformed into fertile sources for communities and wildlife for generations to come.

The mere mention of a Golconda diamond conjures images of a magnificent pure white stone, a rare jewel that originated from India’s legendary mines in the Golconda region. It’s been over a century since the mines were depleted yet a Golconda provenance still has gravitas. It signifies a diamond’s character, quality, and its journey. Natural diamonds are finite, and like the Golconda source, every mine has a limited lifecycle.

Today we expect our diamonds were responsibly recovered from the earth, and that they benefited the local communities where they originated. But what happens after the mine is exhausted? That is another chapter in a diamond’s story with a far-reaching impact for generations to come.

Over the past 30 years, as the diamond mining industry improved and evolved, it has made the process of the mine’s closure an integral part of the activity, one that is baked into the site’s development even before a single diamond is extracted. Mining companies have taken a progressive approach to rehabilitating the land and protecting wildlife in remote regions in Canada, Africa, and Australia, as well as partnering with Indigenous and local communities, and governments to create sustainable ecosystems, employment and business opportunities.

Planting stakes at De Beers’ Victor mine in Canada as part of the award winning post-closure reclamation program. (Courtesy of De Beers)

It Takes a Village to Close a Diamond Mine

If it sounds too good to be true, consider what’s happening in Canada’s Northwest Territories, a remote, sometimes inhospitable region where some of the most beautiful, pristine diamonds are unearthed.

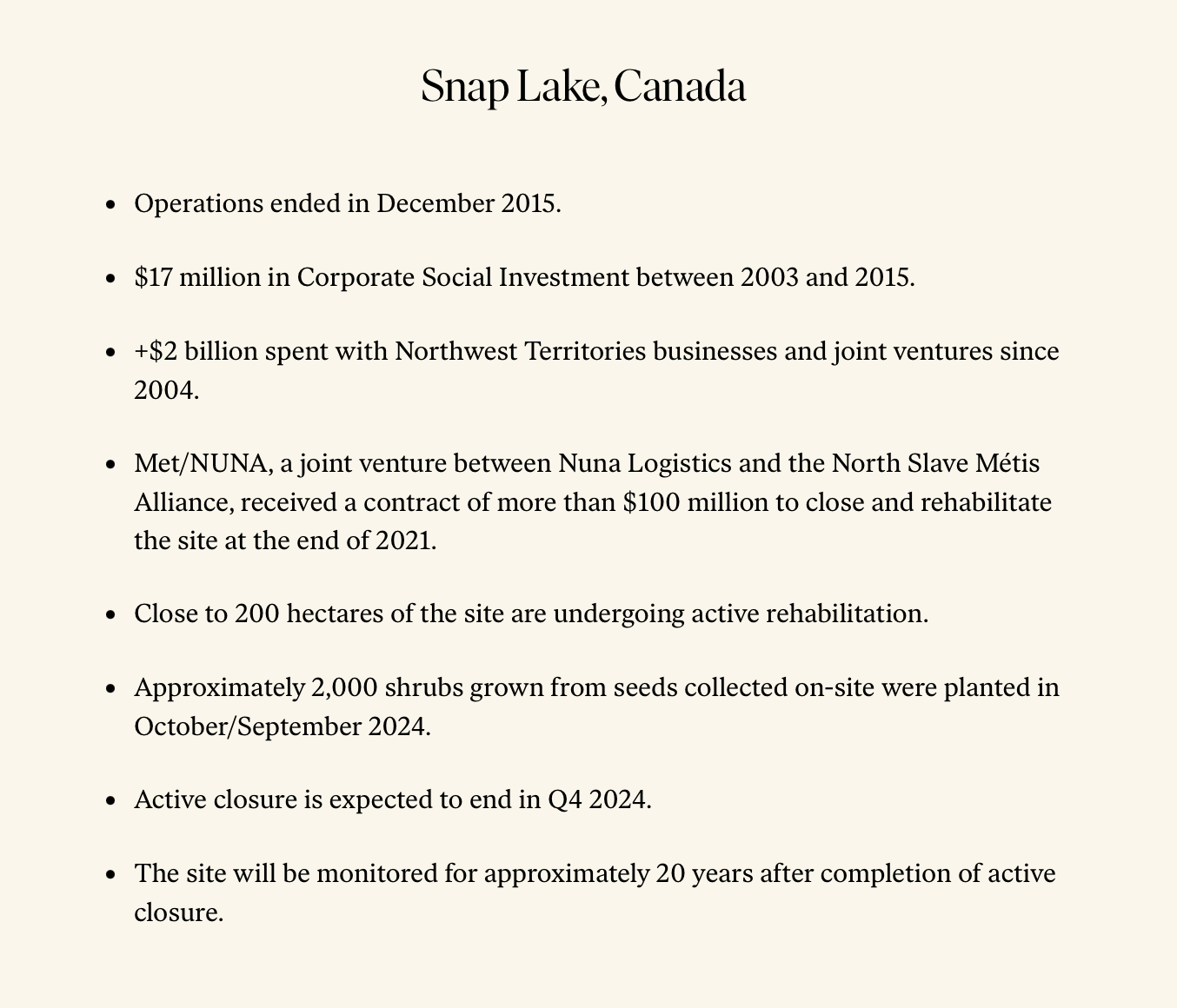

When De Beers Group prepared to close its Snap Lake Mine, it issued a $100 million plus contract to MET/Nuna, an Indigenous community-led joint venture between the North Slave Métis Alliance and Nuna Logistics, to manage the site’s closure and rehabilitation. The partnership ensures that Indigenous communities can prosper for years to come, says Marc Whitford, president of the North Slave Métis Alliance. The project, he says, “will equip us to meet the challenges of tomorrow while still maintaining our strong ties to our lands and customs.”

Beyond delivering training, jobs, and resources to the region, the objective, says Whitford, “is to take a meaningful part in development and share our voice in equality alongside our other aboriginal governments.”

This was not always the case in the remote Northwest Territories. Back in the 1990s, after the gold mines were depleted, the Yellowknife community was left with two massive, abandoned mines and a lack of support, said Michelle Peters, the De Beers Group’s Closure Manager, Canadian Operations. When diamonds were discovered a few years later, she said the greatest obstacle was to build trust in the community. A native of South Africa, Peters has worked for De Beers for 21 years and moved to Yellowknife in 2013.

Employee at the Diavik Diamond Mine in Northwest Territories of Canada. (Courtesy of Rio Tinto)

Even before the mining began, she said, “We started by soliciting the input from the elders to make sure their needs were met. They wanted to make sure that the water was clean, the fish edible, and know they could safely traverse the land. Those are the very simple needs that we are meeting today through very complex solutions.”

The fact is nobody knows the land better than the First Nations people who have inhabited the region for countless generations. Local leaders are working side by side with mining companies to ensure their plants, wildlife, and traditional ways of life are preserved. Still, Peters admits closing a mine is a complicated endeavor that requires resources, innovative thinking, and, most importantly, collaboration.

Five years before the Victor Mine in Northern Ontario ended mining operations in 2019, reclamation of the land began with the newly established Attawapiskat First Nation youth-based seed collection program to harvest and cultivate seeds from the region for future planting. The result: More than 1.4 million trees and shrubs were planted on the mine’s site.

From massive initiatives, such as filling the Victor Mine pit with water using bioengineering to create an expansive lake, down to the small details, like recycling and reusing every piece of mine equipment, De Beers Group has partnered with stakeholders to adhere to the environmental standards while listening to the local needs.

Nature surrounding the Argyle Diamond Mine in Western Australia. (Courtesy of Rio Tinto)

Victor Mine’s new fishpond, for instance, is critical to returning the land’s natural resources. Teams worked together to create a robust habitat and spawning grounds for all types of fish native to the area, including Brook Stickleback, Northern Pike, and White Sucker.

Once systems are put in place, De Beers will continue to monitor the Victor Mine activations and support the community’s efforts for the next 20 years until at least 2039.

Life After The Argyle Diamond Mine Closure

Like a Golconda provenance, a diamond unearthed at the renowned Argyle mine in the remote east Kimberly region of Western Australia has a coveted legacy. The Rio Tinto-owned mine, which after nearly 40 years ended production, has been the world’s only consistent source of rare pink diamonds, and the even more rarified Argyle red diamonds.

As with the Snap Lake and Victor Mines, Rio Tinto began planning the mine’s closure even before it excavated the first diamonds. Located on the traditional lands of the Miriwoong, Gija, Malgnin, and Wularr people, the mining company enlisted their support to plan for life after the mine. It took into consideration water usage, biodiversity, and research into native plants and vegetation. This included the development of resources for those who will continue to live on the land long after the mine is closed. Argyle is working with Traditional Owners (groups who have an historical relationship to the land) to rehabilitate the area around the mine, undertaking revegetation activities to enable the re-establishment of a self-sustaining ecosystem that resembles the surrounding landscape, and returning it to the people who have occupied the land for tens of thousands of years.

The mine’s ‘Life after Argyle’ program is an innovative initiative that provides job training, and education, and helps nurture business start-ups. The closure process is expected to take some five years to decommission and dismantle the mine and rehabilitate the land, followed by another decade of monitoring.

This crucial initiative began in the years leading up to the mine’s final production and will be replicated when Rio Tinto closes its Diavik mine in Canada’s Northwest Territories in 2026.

By The Numbers

A Diamond’s Legacy

What happens after a mine closes also speaks to today’s conscientious consumers who want to know that their natural diamond purchase contributed to a positive and lasting impact.

Mine closings aren’t often discussed, explained Peters. “People get excited about diamond exploration and diamond discoveries, but mine closings are also something to get excited about,” says Peters. “It’s an opportunity to shape the future.”

What’s happening on the ground in the Northwest Territories, she says, sets new standards and shows what’s possible with capital and when people work together.

“This isn’t our story to tell,” said Peters, “but years from now, it will be the community’s story to share. They will be able to tell future generations that we didn’t walk away from the community, the land, and the water, and that we set aside the resources to restore and rehabilitate the land for the people and future projects. In the process, we invested billions in education, healthcare, and more.”

“We hope the diamond’s legacy will be one of collaboration, innovation, and opening opportunities for a better future.”

Source: Natural Diamond Council