History of Diamond Cutting

Since their discovery, natural diamonds have captivated humanity with their unparalleled hardness and mysterious beauty. Their extreme resistance to shaping and polishing filled them with folklore and superstition. It took thousands of years before humans devised the first successful diamond-cutting techniques.

Historical texts tell us that by the 6th century, Indian lapidary workers and 10th-century Islamic jewelers used diamond dust to polish other gems, but diamonds themselves remained uncuttable. An Indian text from the 13th century named The Agastimata is the first to mention diamond cutting, saying, “The diamond cannot be cut using metals and gems of other species, but it also resists polishing, the diamond can only be polished by means of other diamonds.” Supporting this timeline, notable jewelry historian Jack Ogden reports seeing 13th-century Islamic jewelry containing simple table-cut diamonds. These would likely be the first known cut diamonds, marking the beginning of the story of diamond cutting.

De Clercq Roman Rough Diamond Ring, 3rd – 4th Century AD. Les Enluminures

Although the Romans valued diamonds for jewelry as early as 100 BCE, they could only use uncut or rough diamonds. The Roman philosopher Pliny described diamonds as the most precious of all possessions in his book Naturalis Historia in AD 79. Despite the Romans’ obsession with the gem, historical evidence suggests they likely only had access to imperfect diamond crystals, as India, the sole source of diamonds until the 18th century, reserved the best for its native market. The decline of the Roman Empire saw diamonds vanish from European jewelry due to the lack of Roman merchants bringing them from India. However, diamonds remained popular in Indian and Islamic cultures.

European diamond cutting began in Venice around 1330, following the opening of the first trade routes to the East since the fall of the Roman Empire. Venetian merchants now had access to diamonds, and it is likely that they also learned the rudimentary cutting techniques practiced by Islamic merchants and brought them to Venice. Although perfectly shaped diamond crystals were still rare in Europe, one could argue that the lack of ‘ideal’ rough diamond crystals is why the Europeans began to cut diamonds and advance the techniques further and further.

Tudor table cut diamond ring, circa 1485-1603. (Courtesy of Berganza)

Tudor table cut diamond ring, circa 1485-1603. (Courtesy of Berganza)

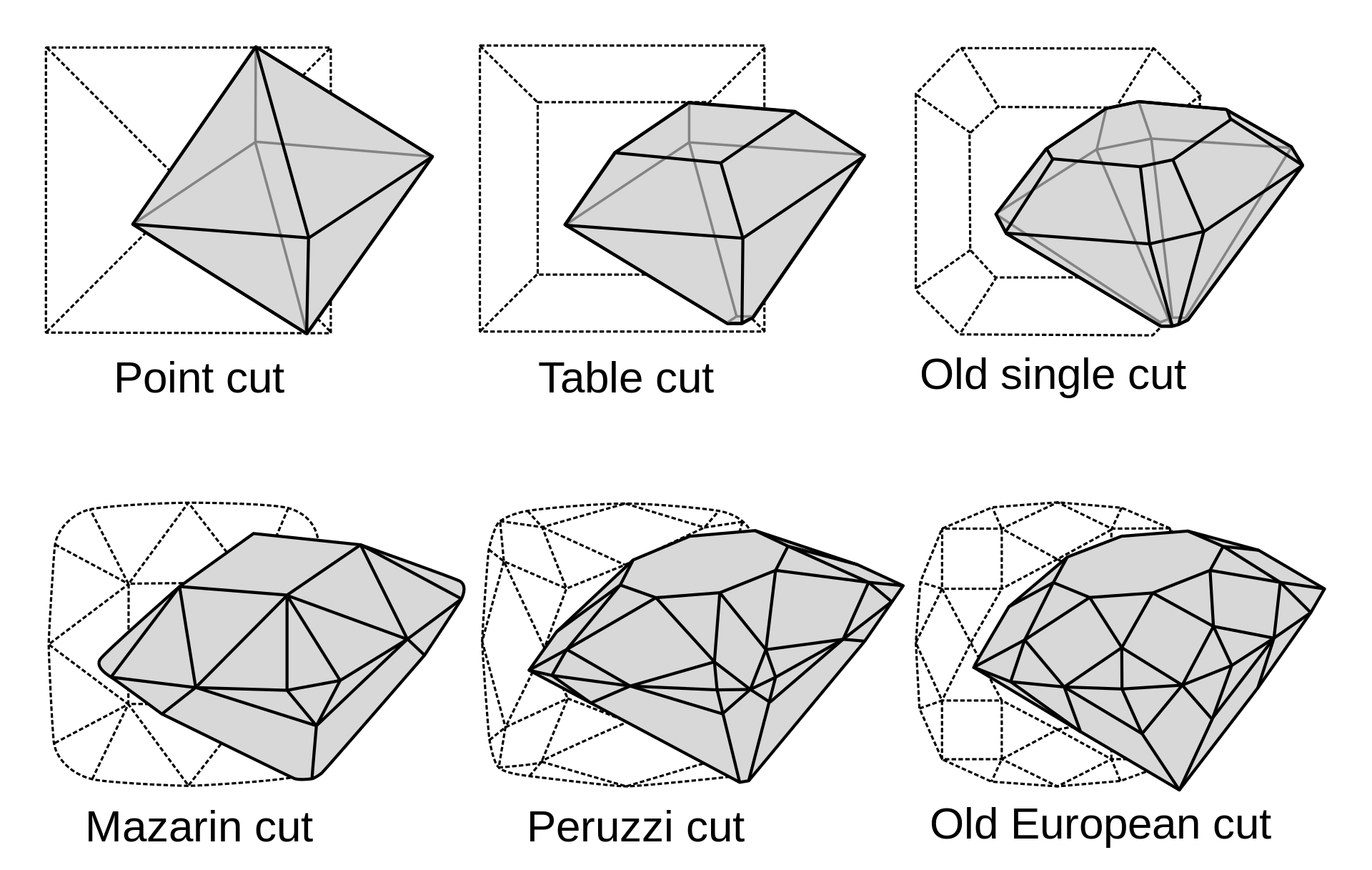

The advent of continuous rotary motion in tools during the 15th century revolutionized diamond cutting beyond just superficial polishing of the rough crystals and ‘cleaving’ or breaking the diamond along its weakest points. This innovation allowed cutters to grind facets into diamonds more efficiently, expanding the possibilities for creative designs. The Portuguese conquest of Goa in 1510, which became the main diamond port of India, increased Europe’s access to high-quality diamonds for the first time.

Europe’s economic center shifted to the North Sea, and as a result, the first diamond-cutting communities in Paris, Bruges, and Antwerp developed. The cutters were mostly Jewish, as it was one of the few professions they were not barred from participating in at the time. By the end of the 15th century, diamond cutting had advanced beyond the limitations of the rough, marking the true beginning of the art. The 16th century saw a shift from mere polishing to genuine faceting, leading to the creation of new cuts. Longer rectangular stones were forerunners to the baguette cut, and the most popular cuts were more refined versions of the table and point cuts. Many earlier cuts also received additional facets to improve their appearance.

Wedding ring with a rose-cut diamond heart clasped between two enameled hands. It is inscribed ‘Dudley and Katherine united 26 March 1706.’ (Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum)

Most importantly, the rose cut emerged during this period and gained popularity for its flat-bottomed design with a crown covered in diamond-shaped facets. Belgian and Dutch cutters specialized in this cut, turning thinner bits of rough into the new standard rose cut. As its popularity grew, the rose cut evolved, with the dome shape becoming higher to accommodate bulkier rough.

Simultaneously, India’s diamond cutting also advanced. Indian techniques, while differing in materials and methods—such as the use of wood versus steel—shared similarities with European practices. The Mughal cut became prominent here between the 16th and 18th centuries, characterized by a large flat base, organic shape, and a sloping array of smaller facets. Unlike most diamonds cut in the West, the Mughal cut followed the shape of the rough and is best understood as a style rather than a specific shape.

An early example of a Mughal cut diamond. The 189.62-carat Orlov Diamond in the Russian Imperial Sceptre. (Image Courtesy of Elkan Weinberg)

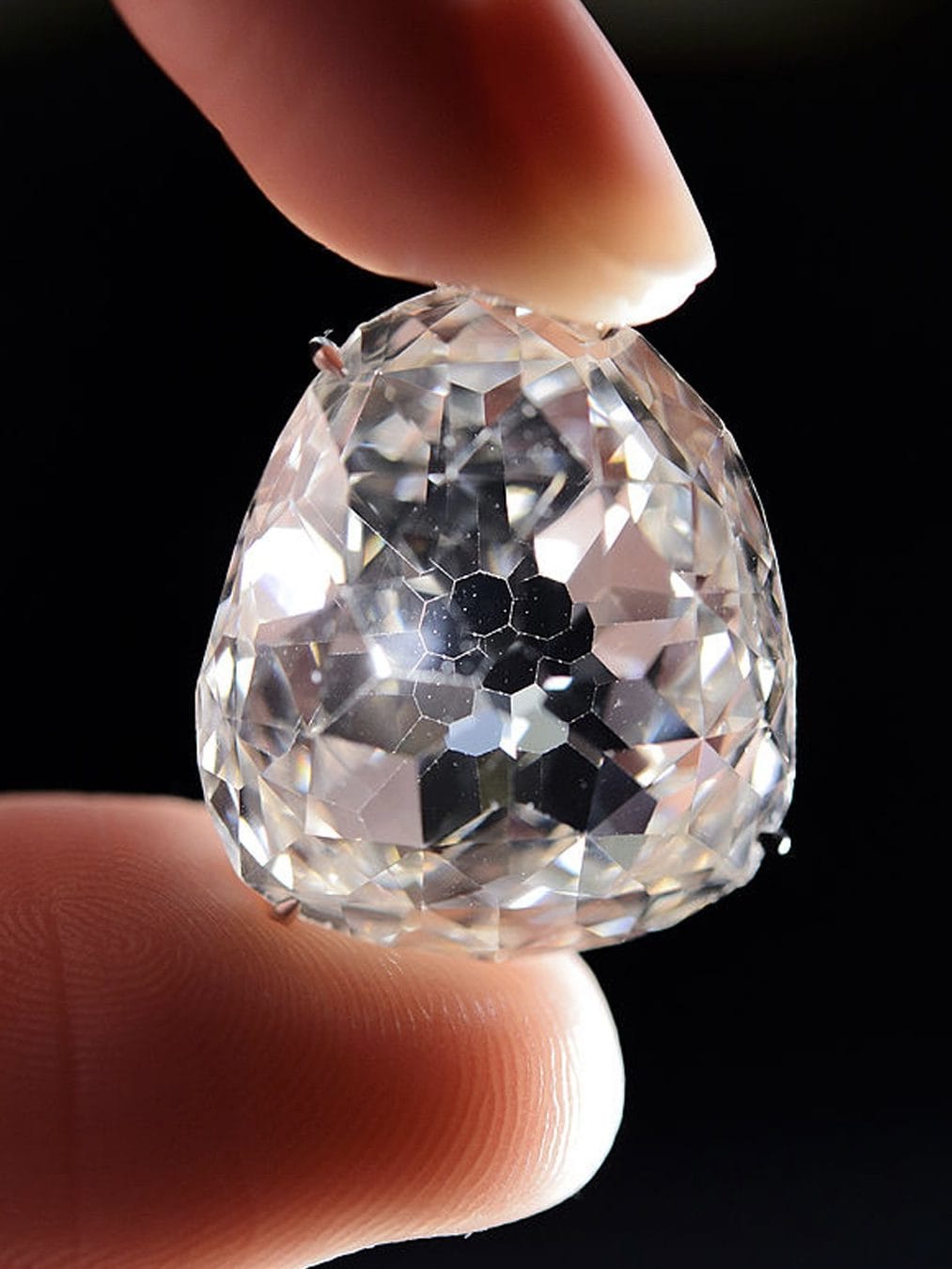

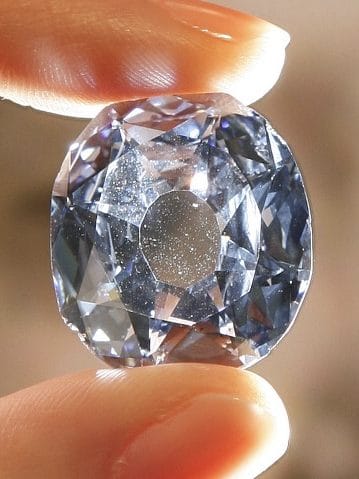

The 17th century brought a new vision of what diamonds should look like. The opulent candle-lit dinner parties of the era demanded more brilliance, leading to the development of the brilliant cut. Early brilliant cuts varied in outline depending on the rough from which they were fashioned. Most importantly, these brilliant cuts were characterized by a pavilion-based design, where the bulk of the weight was in the lower part of the stone, allowing more light to return to the top and giving the diamond the signature sparkle we know today. This pavilion-based style is now the basis for most modern cuts.

An early example of a brilliant cut, c 1600s. The 55.23-carat Sancy Diamond, located at the Louvre, Paris.

An early example of a brilliant cut, c. 1600s. The 35.56-carat Wittelsbach Diamond (Getty Images)

The Mazarin cut, invented by French Cardinal Mazarin in the mid-1600s, was the first true brilliant cut featuring 17 crown facets. The Peruzzi Cut, developed in the 1700s, improved upon the Mazarin cut with 33 crown facets and was known as the triple-cut brilliant. Like the Mazarin cut, the Peruzzi cut was cushion-shaped and served as the inspiration for the old mine cut.

King Louis XV of France commissioned the marquise cut in the mid-18th century to reflect the shape of his mistress, Marquise de Pompadour’s mouth. This cut and others represented variations of the brilliant design suited to different rough shapes. Despite these innovations, table cuts, point cuts, and rose cuts remained prevalent until well into the 18th century when diamonds from India became more scarce, and the old cuts started to be recut en masse for maximum sparkle. This recutting is why so few diamonds cut before this period still exist in their original cut form.

Diamond Cut Evolution

Just as Indian diamond mines began to exhaust, the first diamonds were discovered in Brazil in the early 18th century. The area was fittingly named Diamantina. By 1730, a steady production of Brazilian diamonds became a reality. Individual miners found many small deposits around Brazil during the 18th century, significantly boosting the global supply of diamond rough. Diamonds, once reserved for European nobility because of the miniscule supply, became available to a broader public, causing the diamond-cutting industry to grow. The old mine cut, an evolution of the Peruzzi cut, rose to prominence during this time.

The rise of a prosperous middle class in Europe and the United States during the 19th century led to a surge in diamond jewelry’s popularity. However, as Brazilian supply dwindled by the mid-19th century, diamond prices rose, and European cutting centers, particularly in London, Antwerp, and Amsterdam, faced challenges.

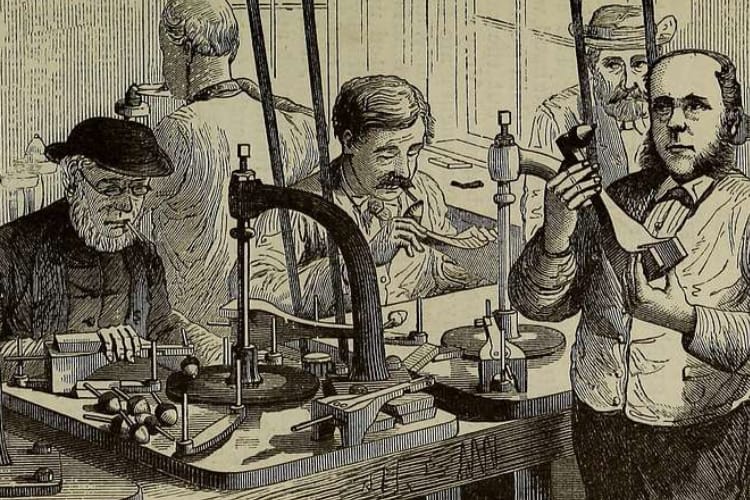

Diamond cutters in NYC 1870s

Fortuitously, the discovery of the Eureka diamond by a 15-year-old boy in South Africa in 1867 marked a pivotal moment for the diamond industry. This find sparked the South African diamond rush, revived the Dutch and Belgian diamond-cutting industries, and provided diamonds at a time when it seemed the world’s supply had come to an end.

The South African diamond rush led to significant innovations in diamond cutting. The bruting machine, invented in the early 1870s, allowed for the first truly round brilliant cuts, known as Old European cuts. The motorized diamond saw, invented by a Belgian in 1900, revolutionized the shaping of diamonds. An American cutter, Henry Morse, perfected the round brilliant cut using scientific principles of light performance. Marcel Tolkowsky later published the definitive work on diamond cutting, establishing the brilliant-cut we know today.

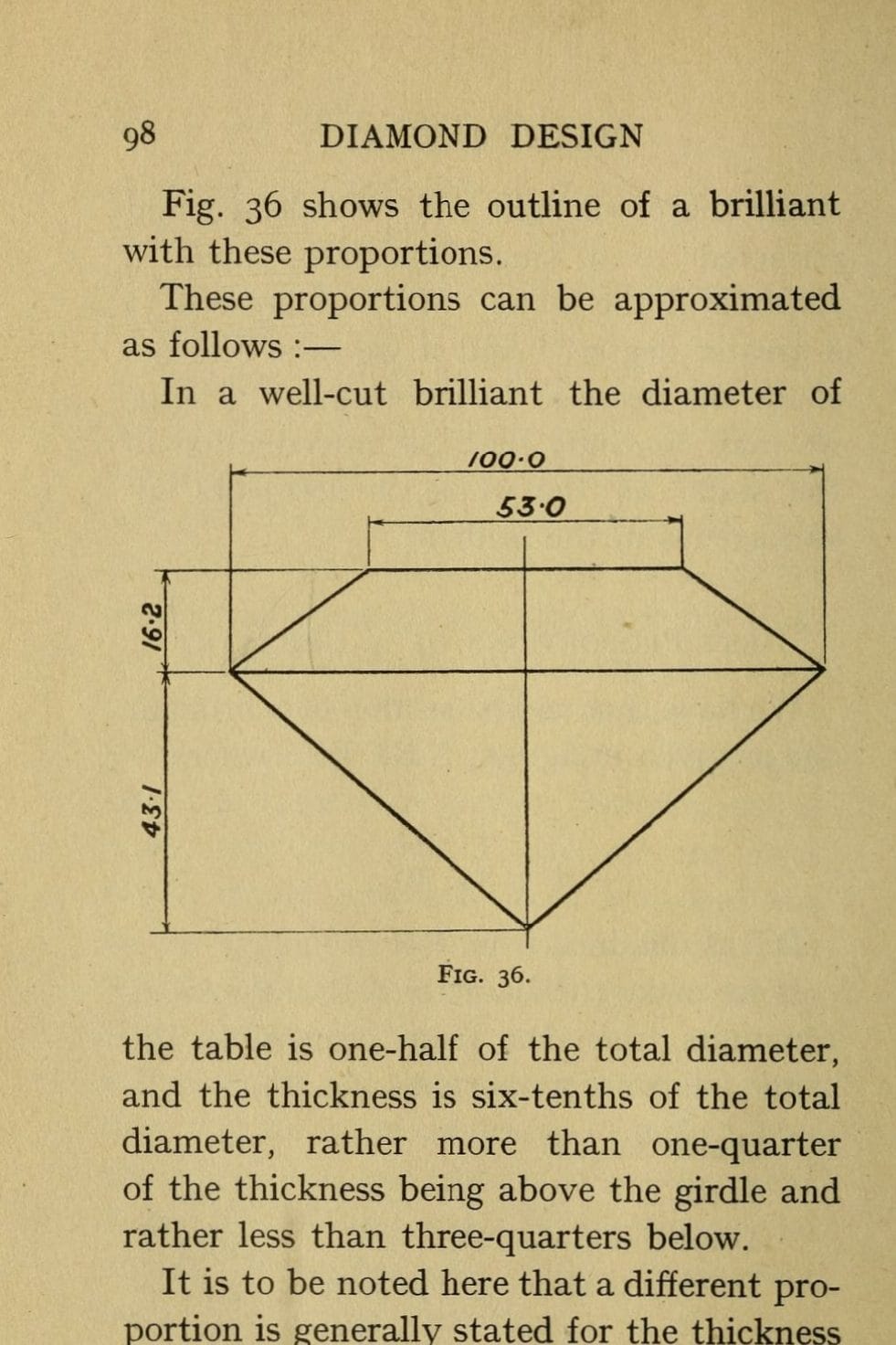

Diamond Design c. 1919

Diamond Design c. 1919

Aside from perfecting the round brilliant cut, the new technology and knowledge allowed for master cutters of the 20th century to innovate with modern cuts like the Asscher, which was created by Joseph Asscher in 1902 and is considered the first patented diamond cut. Most familiar cuts, including the emerald, oval, princess, and radiant, also came along in the mid-20th century. The diamond-cutting centers of Europe, where so much of this innovation had taken place over the last 400 years, were predominantly Jewish-owned and operated. Sadly, they experienced devastation during World War II and never fully recovered. However, with the help of Jewish immigrants and refugees, new centers emerged elsewhere, notably in Israel and India. Today, India leads the world in diamond cutting, fittingly for the country where diamonds were first discovered and likely first cut.

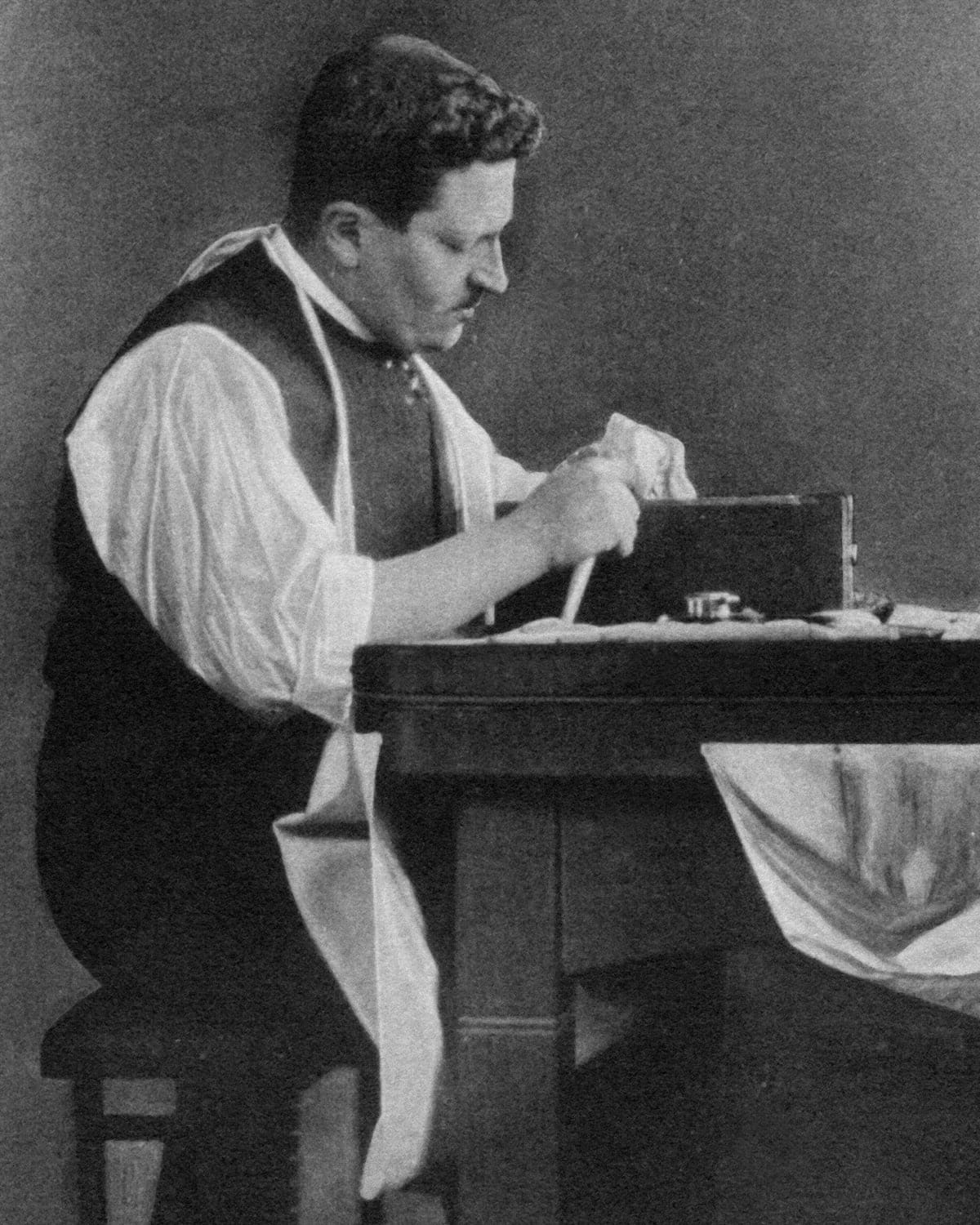

Joseph Asscher works on the Cullinan

The Royal Asscher-Cut

The history of diamond cutting is a tale of innovation, artistry, and resilience. From India to Venice and beyond, the brilliance and beauty of natural diamonds, shaped by centuries of craftsmanship, continue to captivate and provide livelihood for millions.

Source: Natural Diamond Council