Guide to Tourmaline

History, Lore and Appreciation

Tourmaline is a group of closely related minerals composed of several species and varieties. The celebrated gemologist and author, Eduard Gübelin, referred to it as a “crystallized kaleidoscope” because of the diversity of colors that make up this rich family. Tourmaline comprises colors of the spectrum from red to violet and practically any degree of variations

in between. Tourmaline can also be bicolored, colorless or black. Tourmaline’s variety names are often designated by these hues. However, most of the gem tourmaline used in jewelry today belongs to the elbaite, rossmanite, fluor-liddicoatite and dravite mineral species, which exhibit the strongest and brightest colors.

The name tourmaline derives from the Sinhalese word turamali, meaning gemstone with mixed colors. In the early 1700s, traders from the Netherlands brought turamali back to Europe from Ceylon (Sri Lanka). They were fascinated with the material’s apparent electrical characteristics – which later were scientifically determined as this gem’s unique piezoelectric and pyroelectric properties. When tourmaline is heated, it develops positive and negative charges at opposite ends of the crystal. Those who smoked pipes appreciated the gem’s apparent magnetic ability to draw ashes out of their pipes, which gave it the nickname aschentrecker, meaning “ash puller.”

Curiously, tourmaline had already arrived on European shores at the time of Pliny the Elder. In his famous series of books on natural history, Pliny described similar electrical properties in a gemstone he named “lychnis.” Because he also noted that it was reddish or violet in color, it is believed the gem was probably tourmaline.

Confusion was sown in the 1500s when Portuguese explorers looking for emeralds in Brazil chanced upon rich, green, emerald-looking gemstones. Swiss naturalist, Conrad Gessner, saw this material in Europe. Though he classified it as “emerald,” he also included the word “Brazilian” in front of it. Obviously, in this case, Brazilian “emerald” wasn’t quite the same as the Colombian material. It was tourmaline.

In recent years, tourmaline has witnessed a true renaissance, particularly after the discovery of a copper-rich elbaite tourmaline from the State of Paraíba, Brazil. While the locality produced a modest quantity of material for a short time, its vivid colors, (described in the trade as “neon” or “electric”) caused by copper impurities, were considered so unique that they revolutionized the tourmaline business. Demand for all varieties of tourmaline has enjoyed an increase since the late 1980s, when cuprian elbaite was first discovered. Since then, similar colored copper and/ or manganese rich tourmaline has been found elsewhere in Brazil as well as in Nigeria and Mozambique.

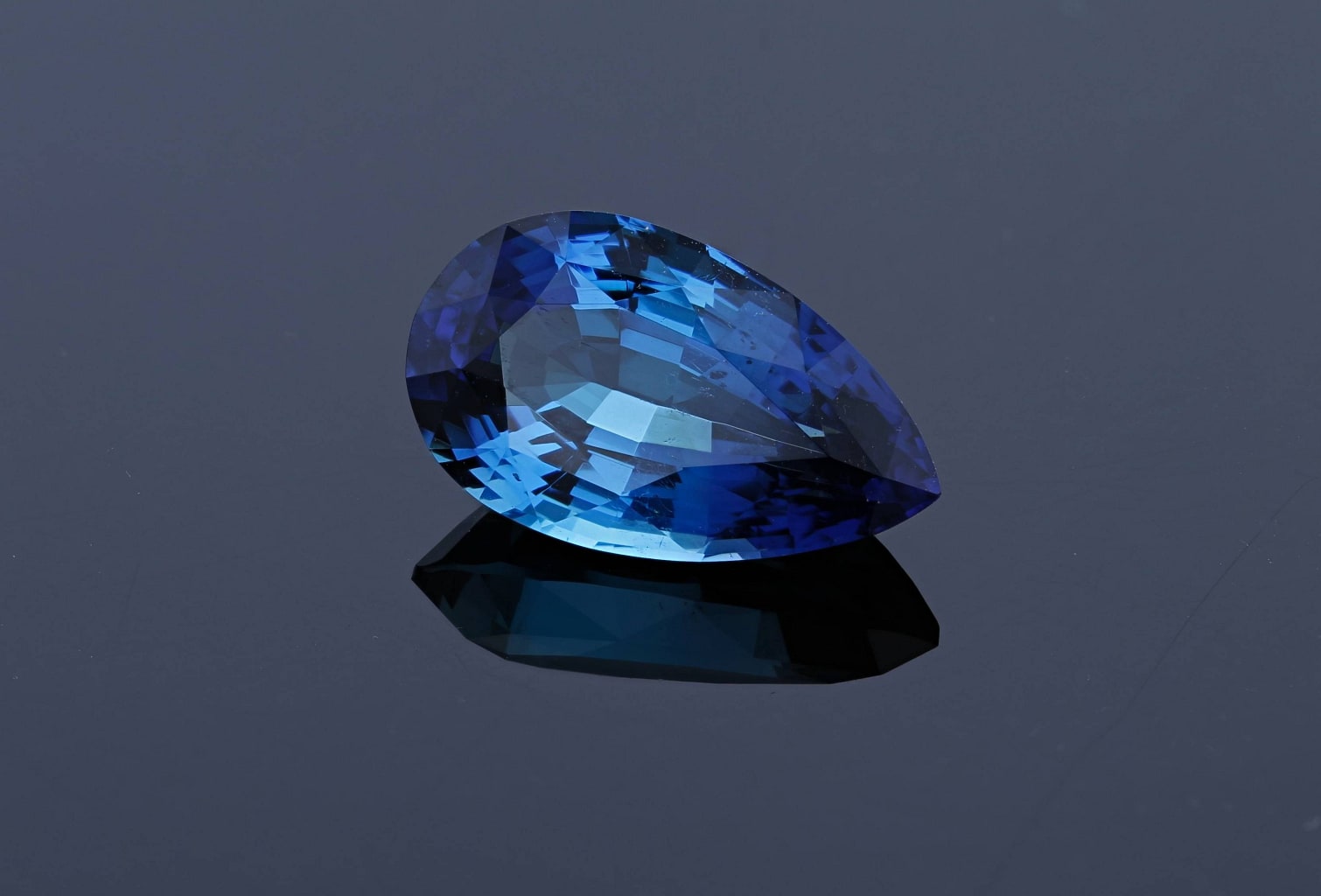

Paraiba tourmaline. Source: Smithsonian

Paraiba tourmaline. Source: Smithsonian

Birthstones and Anniversaries

Tourmaline is one of the birthstones for the month of October, along with opal.

Description and Properties

Tourmaline is a vast and complex mineral group that has many species, including the following with relevant gem varieties: dravite, uvite, rossmanite, schorl, tsilaisite, elbaite and fluor-liddicoatite. Tourmaline crystallizes in the trigonal crystal system, mostly as trigonal, prismatic crystals. Tourmalines are extremely complicated borosilicates, and the formula for many of the mineral varieties varies considerably. By way of example, International Mineralogical Association (IMA) approved formulas for some tourmalines are as follows:

Dravite: NaMg3All6(BO3)3Si6O18(OH)3(OH)

Fluor-Liddicoatite: CA(Li2Al) Al6(BO3)3Si6O18(OH)3F

Elbaite: Na(Li1.5Al1.5) Al6(BO3)3Si6O18(OH)3(OH)

Principal color varieties:

Rubellite: Pink to red range, may also be brownish, orangey, or purplish.

Verdelite: Yellow green to bluish green.

Indicolite: Violetish to greenish blue.

Paraiba tourmaline: Vividly colored blue to green gems in which the unusual hues result from traces of copper and/or manganese.

Dravite: Yellow to brown; the bright yellow color has been called “canary tourmaline” in the trade.

Achroite: Colorless

Multicolor: Two or more colors (if only two colors are seen, these gems are called bi-colored).

Watermelon: Pink centers with green around the outer margins of the stone.

Chrome tourmaline: A deep, solidly green, chromium-containing gem.

Cat’s eye tourmaline: Tiny hollow growth tubes in some cabochon-cut tourmaline cause a cat’s eye effect in direct lighting.

Liddicoatite: This is the fluor-liddicoatite species of tourmaline, a calcium-rich, lithium tourmaline that was named in 1977 in honor of one of GIA’s founding fathers, the noted gemologist, Richard T. Liddicoat. This is a usually a parti-color tourmaline par excellence and often exhibits many colors in strongly zoned, geometric patterns.

Refractive Index: 1.624 to 1.644 (+0.011, -0.009)

Birefringence: 0.018 to 0.040

Specific Gravity: 3.06 (+0.20, -0.06)

Cause(s) of color: Blue: iron. Red and pink: manganese and some titanium. Green: iron, chromium and vanadium.

Paraíba colors: copper and/or manganese.

Mohs hardness: 7 to 7.5

Internal identifying characteristics: Tourmaline has abundant fluid inclusions, which look like thin, threadlike and elongated fingerprints. Some tourmaline also contains elongated hollow tubes that form in parallel fashion during growth, and these exhibit cat’s-eye phenomena.

Treatments

Heating: This treatment aims to produce lighter green and blue green colors from overly dark gems. In cuprian elbaite, heating causes some dark manganese- bearing purple material to become strongly greenish blue or deep blue. There are some undesirable effects of heating: some pink and red tourmaline may fade to nearly colorless upon heating.

Irradiation: This treatment can be used to reportedly produce darker manganese- bearing red gems from light pink. However, it is not possible to determine treatment gemologically.

Fracture filling: This treatment is used to conceal surface reaching fractures and fissures.

Collector Quality

The term “Paraíba”, derives from the Brazilian state in which particular copper- bearing tourmalines were first found. However, it soon became a widespread descriptor for the saturated colors caused by copper and/or manganese, even those found in different localities. Later, more copper bearing tourmalines were found in the neighboring state of Rio Grande do Norte, Nigeria and Mozambique. Ultimately, copper and manganese bearing tourmaline may be called “paraiba tourmaline” in the trade. Regardless of their geographic origin, such gems highly sought after by many collectors.

Rubellite with strong color, especially from sources that produced high qualities for short times, such as Nigeria, is collectible. Indicolite, sometimes also called indigolite, that exhibits strong blues are also very popular.

Bi-color or parti-color tourmaline shows strong color zoning, parti-color gems and cat’s eye tourmaline is also collected. In rare instances when “chrome” green tourmaline is found, they are collectible, especially in larger sizes because of their vivid green color.

Paraiba tourmaline from Brazil. Source: Smithsonian

Paraiba tourmaline from Brazil. Source: Smithsonian

Localities

Brazil remains the world’s largest producer of tourmaline in all colors. The States of Paraíba and Rio Grande do Norte have produced Brazil’s most coveted cuprian (copper bearing) tourmaline. Afghanistan is known for a very bright blue green quality of tourmaline, though it also produces some green and pink material. Myanmar (Burma), India, Kenya, Mozambique, Pakistan, Nigeria, Sri Lanka, Russia, Tanzania all produce significant quantities of material in various colors. The United States – California and Maine, and particularly the Pala district in Southern California, is known for producing rich

pink tourmaline and rubellite. Madagascar primarily produces rubellite and liddicoatite tourmaline. Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe are also sources.

Cutting, Care and Cleaning

Tourmaline’s elongated, prismatic crystals dictate how the gemstones are cut, often resulting in very long, rectangular shapes. While tourmaline can be cut in all shapes and sizes, rectangular shapes predominate. Crystals often exhibit more than one color; in such cases bi-color or parti- color gemstones result. On occasion, tourmaline is also carved.

While tourmaline has adequate hardness, there may be zones of weakness in some gems, particularly those that have many inclusions. Some bi-color tourmaline is weaker along the color boundaries.

Tourmaline should not be steam cleaned or placed in an ultrasonic cleaner for these reasons. Instead, it should be cleaned with a soft damp cloth or a soft bristle toothbrush.

Source: CIBJO Retailers’ Reference Guide