Guide to Opal

History, Lore and Appreciation

The name opal likely derives from the Latin word opalus, and was mentioned in Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, though some scholars point to ancient Sanskrit descriptions, and the root word, upala. Human fascination for the gemstone is due to some of its principal features: its phenomenal nature and extraordinary range of hues. In the numerous varieties of opal, many spectral colors can be enjoyed within a single gem. It is this colorful complexity about opal that caused naturalist Pliny the Elder – in the first century CE, to write following:

“There is in them a softer fire than the ruby, there is the brilliant purple of the amethyst, and the sea green of the emerald, all shining together in incredible union. Some by their splendor rival the colors of the painters, others the flame of burning sulfur or of fire quickened by oil.”

In 1550, Italy’s brilliant mathematician and naturalist, Girolamo Cardano, noted in his monograph, De Subtilitate Rerum, (The Subtlety of Things), a study of natural phenomena, that he had once bought [an opal] for fifteen gold crowns. His enthusiastic observation was that, compared to a diamond costing him thirty-three times as much, the opal had brought him much greater pleasure. Part of his enchantment may have been that one opal never looks like another because play-of-color patterns change from gem to gem. Like the people who wear them, each opal is unique.

Other writers have invoked opal as well. Shakespeare alludes to the changeable nature of opal in his play, Twelfth Night, when he contrasts the versatile personality of one of its characters to the gem. He also described opal as “the queen of gems.”

Dark jubilee opal. Source: Smithsonian

Dark jubilee opal. Source: Smithsonian

Opal’s phenomenal nature has clearly brought enjoyment to many, but it has also evoked unwarranted superstitions. Because of a work of fiction by Sir Walter Scott, “Anne of Geierstein” written in 1829, attributing “enchanted powers” to an opal, some readers mistakenly began to think of opal as an unlucky gem. In the century elapsed since then, opal has regained its rightful reputation as an adaptable gem of beauty. In Australia, where the vast majority of the world’s opal is mined, the gem – especially black opal – is in fact perceived as lucky. Australian aborigines, for example, attributed opal’s discovery with the simultaneous, and fortuitous discovery of how fire can be tamed and utilized.

There are two broad classes of opal: precious and common. While fiery colors – and play-of-color has always been precious opal’s principal asset, common opals can be colorless, composed of a single body color, or be opaque, translucent or transparent with no play-of-color.

During opal formation, silica may substitute or replace an organic host, taking on some of its physical characteristics. As such, opal may form as fossils by replacing clam shells, snails, bones, trees or branches, and in the hollow inside joints of bamboo stalks. Here, the opal takes on the outward appearance of the item it replaced. However, most opal forms in seams or cracks within harder rocks such as sandstone, basalt, ironstone, quartzite or rhyolite.

It is not surprising that there are several dozen types or varieties of opal, not all of which can be described here. The main commercial varieties are:

White opal: Translucent to semi- translucent opal, with play-of-color against a white or light body color.

Black opal: Translucent to opaque opal, with play-of-color against black, grey, blue, green or brown body color.

Crystal opal: Transparent to semi- transparent gem opal that has an essentially colorless body color, but often shows play of color.

Fire opal: Transparent to semi- transparent opal with a range of light yellow to deep orange body color. These gems may have play-of-color or none at all.

Jelly opal: Transparent to semi- transparent light to orangey-colored opal and exhibits no play-of-color.

Contra-luz opal: Transparent opal that shows play-of-color when light is transmitted through it. Mexican opal often shows this characteristic. The Spanish words contra luz literally translate to “against light.”

Boulder opal: An opal seam in the matrix host rock where it formed, namely ironstone. These can be very thin but still exhibit extraordinary play-of-color.

Moss opal: Translucent to opaque opal with no play-of-color that contains dendrite inclusions of another mineral or of oxides that cause a moss or fern-like appearance within the gem.

Oolitic opal: Opal that contains very small dark black or brown spherical areas that looks like fish roe in appearance. This material has play-of-color.

Hydrophane: An absorbent variety of opal that may have play-of-color. Some material may appear as common opal when dry, but which develops play-of-color phenomena when immersed in liquid.

Birthstones and Anniversaries

Opal is one of the birthstones for the month of October, along with tourmaline. Opal is also considered an appropriate gift to commemorate a 14th wedding anniversary.

Description and Properties

Opal is an amorphous or poorly crystallized material, essentially composed of hydrated silica with the following composition: SiO2·nH20. Tightly packed and arranged, microscopic spheres of silica, of which opal is composed, cause play-of-color. Light reflecting off of, and passing through these packed spheres, frequently causes interference and diffraction of light, which we are able to perceive as play-of-color. This phenomenon may be compared to rainbows, which form as light passes through water droplets in air. While opal may be essentially colorless to light orange, it can still have play-of-color that is revealed as the gem catches the light.

Color(s): Many colors are seen in opal. Body colors can vary from white to dark blue and to black, with brown, red orange in between. In recent years, translucent, vivid greenish blue, as well as pink common opal varieties have been discovered in Peru, Mexico and France. A milky, green opal found in Tanzania is called prase opal due to its similarity to the chalcedony variety of prase. Because these gems have no play-of-color, but are attractive for the body color they exhibit, they are often faceted or cut as cabochon gems or beads. Opal may be transparent to opaque; most opal is translucent.

Refractive Index: 1.450 (+0.020, -0.080) Mexican opal may have lower readings, (1.37 to 1.43).

Birefringence: None

Specific Gravity: 2.15 (+0.08, -0.90).

Cause(s) of color: Diffraction-grating related interference colors, as seen as play-of-color, caused by the arrangement of tiny spheres of silica. In green opal, it is caused by nickel impurities, in blue opal by copper and chrysocolla and in pink opal by organic substances.

Mohs Hardness: 5 to 6.5

Internal identifying characteristics: Occasionally, small amounts of matrix, brown ironstone, can be seen through thin seams in boulder opal. Consequently, opal often contains elements of the environment in which they formed. Pyrite, hematite and other minerals may occur as stain plumes or tiny, included crystals. Two and three phase inclusions are rare but may occur. Cristobalite inclusions are common in Mexican opal.

Mexican opals. Source: Smithsonian

Mexican opals. Source: Smithsonian

Treatments

There are several opal treatments. Most are designed to stabilize the gem, deepen the color, or cause the play-of-color to stand out against a darker body color.

Impregnation with oils, wax or polymers: may be used to improve play-of-color and mask the effects of crazing.

Dyeing: Causes lighter opal to look like darker, more-valuable black opal.

Sugar impregnation and smoke treatment: Creates the appearance of black opal.

Black paint backing: darkens the gem improving the appearance of play-of-color.

Opal doublet or triplet: While not within the classic definition of treatments, doublets constitute an artificial product, a composite stone, taken to make thin seams of opal usable in jewelry. A doublet is a thin, natural opal slice that is glued to a strong black substrate, such as dyed black chalcedony. Some glued slices are then capped with transparent quartz cabochons in an effort to protect the thin seam of opal. Two separate materials glued together are called doublets. If a third cap is also used, it is considered a triplet. These assembled stones may also exhibit strong displays of play-of-color.

Collector quality

Collectors prize solid opal (without matrix or backing of the host rock) that displays strong play-of-color, especially in dark body colors. Collectors look for patterns such as “harlequin”, which shows large areas of different colors with straight boundaries when the gem or light source is moved; “pinfire,” which exhibits tiny flashes of multi-color patches. Many other terms apply to different color patterns (e.g. block, Chinese writing, flagstone, jigsaw, peacock tail, ribbon, straw and stripes, are but a few). White precious opal can also show the above- mentioned characteristics. Contraluz opals are also collected because of their relative rarity, and because of their dramatic reactions to light. There are collectors of ironstone-opal nodules from Yowah, an Australian locality. “Yowah nuts” are highly contrasting, large roundish opals, which formed within dark ironstone matrix.

In fact, there is a growing appreciation for boulder opals, due to their strongly contrasting hues and play-of-color. Pink, blue and green opal is rare and therefore collectible as well.

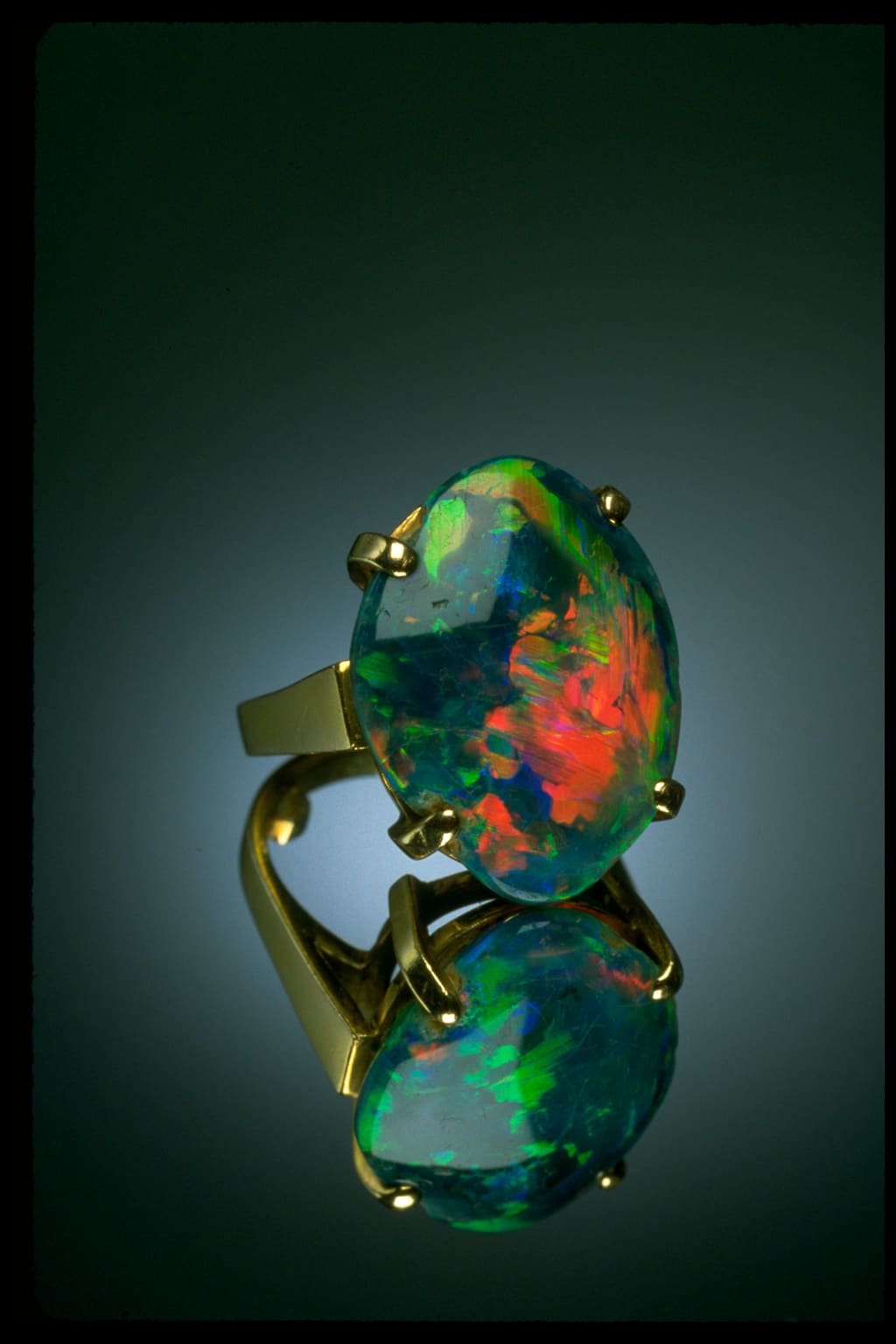

Black opal ring. Source: Smithsonian

Black opal ring. Source: Smithsonian

Localities

Australia produces most of the world’s opal, and some of the finest come from a locality called Lightning Ridge. In the 1950s L. Hudson, a postmaster for the region, wrote a poem describing the area, part of which follows:

There’s a sleepy little township, out beyond the western plains,

Lightning Ridge, the town of opal, where there’s heat and scanty rains.

The location is not scenic, just rough ridges all around

Nature sired her scenes of beauty, in black opal, underground.

Several other Australian localities: Opal is mined in Coober Pedy, Andamooka, Mintabie and many occurrences in Queensland, especially for boulder opal, notably in Yowah and Koroit. Opals have been found since early Roman times in today’s Slovakia. Today it is found also in the United States, Mexico, Brazil, Peru, Honduras, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia (especially hydrophane opal) and Indonesia.

Spiderweb opal. Source: Smithsonian

Spiderweb opal. Source: Smithsonian

Cutting, Care and Cleaning

Because of its water content, opal is sensitive to heat and temperature changes. Opal may develop a network of tiny fissures over time, or if subjected to heat or pressure. These fissures are referred to as “crazing” in the trade. Because opal is delicate, they require gentle, loving care. Opal is rarely faceted because the facet edges and junctions are prone to abrasion.

Most are cut in cabochon shapes, which avoids abrasion along sharp edges. Although some Mexican, Peruvian and crystal opal is faceted and tends to exhibit a sleepy, milky appearance on colorless or colored body color. Cabochons are the main canvas upon which to best exhibit opal’s play-of-color. Dampened soft fabrics with no abrasive or chemical additives, or a soft bristle toothbrush doused with water are the best ways to clean opal jewelry. Gemologists advise against storing opal in a dry environment to avoid crazing.

Source: CIBJO Retailers’ Reference Guide