Understanding Metal Hardness

Learn to use the correct hardness of sheet and wire metals for your jewelry-making techniques.

Knowing how to choose the correct hardness of sheet and wire metals for your jewelry techniques and designs helps you achieve the good-looking, long-lasting results you want. Below, we share some of what we know about metal hardness and we hope it enriches your experience at the bench.

Metal hardness is one of the trickiest things to try to explain—the term is relative to the particular metal or alloy, for starters; depending on the elements that make up each particular alloy, what’s called “hard” in one metal won’t bend, form, works or feel the same as a material designated as “hard” in another metal.

The Hardness Relativity

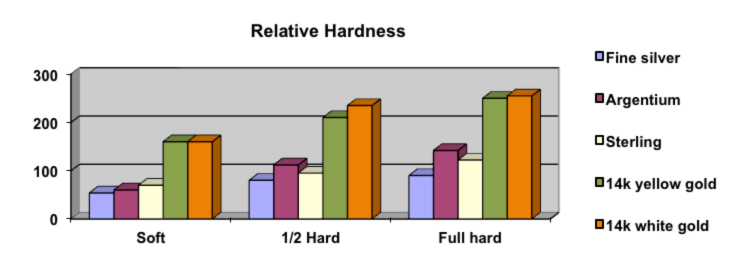

Metal is composed of individual crystals arranged in a pattern and density specific to that type of metal. Because of this, the range of hardness from soft to hard will be relative to each metal (see the Vickers hardness chart below). Dead-soft sterling silver, for example, does not feel or behave the same as dead-soft white gold.

If you will be soldering on the piece you’re making, you may as well start with dead soft because it’s easy to work with and any hardness the metal may have will be lost when you apply heat to solder. If you will be cold-working the metal (manipulating, forging, twisting, folding, etc.), you may want to start with dead-soft metal and anneal it every so often as needed to resolve the work-hardening and return the metal to a dead-soft state. Jewelers who wire-wrap usually use 1/2-hard wire because it holds its form well in the finished design—as the wire is bent to wrap it, the working hardens the wire further so that the finished jewelry is stronger.

Any kind of cold working such as rolling, drawing, bending—even uncoiling and coiling wire—increases the hardness incrementally. Annealing can return the metal to dead soft, and further work will again begin to harden it. Mills that make sheet and wire typically measure the hardness of their products based on how much the product has been worked (a percentage of reduction, for example, in rolled sheet or drawn wire) since they were last annealed to dead soft.

The descriptions below offer, in general, what you can expect from the various hardnesses, but remember that these will vary in degree depending on the metal you’re working with, what you’re making and how you work.

Dead Soft

Metal that is dead soft is in a relaxed state at its molecular level, so it is easy to bend, shape and hammer. The act of bending or shaping will gradually work-harden the metal—right up to the breaking point. Dead-soft metal will not hold its shape if put under stress in structures such as hinges or clasps.

1/2-Hard

Metal that is 1/2-hard has been worked a bit, tightening the grain at the molecular level. This metal is harder to bend and hammer, but it is still possible in some cases to shape the metal—it just takes more force. While still malleable, it will also hold its shape under a certain amount of stress; it is ideal for wire wrapped structures that will support other components. If you are fabricating an item that needs both strength and a thinner gauge, you would probably choose 1/2-hard.

Full-Hard

Metal that is tempered (or significantly work-hardened) will be difficult to bend but will hold whatever bend you put into it pretty stubbornly. This hardness is ideal for clasps or hinges.

Spring-Hard

Metal thoroughly hardened will lose pretty much all of its malleability and will actually spring back into its original shape when bent by hand. This hardness is ideal for ear wires, jump rings head pins and pin components.

More About Hardness

It is important to remember that metal hardness is changeable. Metal alloys will harden and soften in a number of ways. Most metal alloys used to make jewelry become harder from cold-working (stressing) them and can be made softer by a process called annealing.

Work-hardening can be pictured easily if you imagine bending a paper clip. Keep bending the paper clip back and forth, and eventually it breaks. With each bend the wire has become “work hardened” and more difficult to bend until it simply can’t bend anymore and breaks instead. The same thing happens to sheet metal passing through a rolling mill or to wire pulled through a draw plate—each pass makes the metal a bit harder. Twisting wire will work-harden it, too; this is great to know for making ear posts—by adding a twist, you can keep the wire round while giving it more strength. When hammered into shape on a steel plate, sheet and wire become work-hardened (and they take on a nice hammered texture, too). Basically, anything done to the metal (without heat or abrasives) that changes the shape of the metal—such as bending, forming, twisting, stretching and so on—work-hardens it.

The point here is, if you start with dead soft metal and work it or stress it, it will get harder. If you heat and cool alloyed metal in a very specific process, you can harden it. On the other hand, if you take a harder metal and heat it either by soldering on it or by deliberately annealing it, you can soften the metal—all the way back to dead soft, if that’s what you want.

So What Hardness Should I Use?

For our customers, we tend to start by asking questions that can help narrow the options—starting with “How do you want to use your metal?” and “What metal are you using?”

If you will NOT be wire-wrapping:

- Will you be applying any heat to your metal?

- Do you plan to acid-etch the metal?

- What type of jewelry are you making?

If you will NOT apply heat to the metal, we tend to recommend a dead-soft hardness and let the work harden the material in the finished piece. For items such as cuff bracelets, we tend to recommend 1/2-hard because they will further work harden, and you want the finished piece to be stronger than, for example, a pair of earrings. If you WILL be applying heat, start with dead soft because the heat will remove any hardness anyway. You can harden the finished piece as needed (see heat-hardening link below). If you plan to acid-etch the metal, we tend to recommend 1/2-hard or spring-hard varieties.

If you WILL be wire-wrapping, we tend to recommend:

- For sterling or Argentium®Silver, use 1/2-hard. (Argentium tends to work-harden more readily than traditional sterling, so you may want to try a dead soft in that metal to see how it suits your work.)

- For 14-karat white gold, use dead-soft.

- For yellow gold, use 1/2-hard for 19–22 gauge; use dead-soft for 18 gauge and heavier.

- For base metals, dead soft is the starting point for just about everything and can be work-hardened if needed.

If your finished silver or gold pieces will take some stress when worn (rings or bracelets, for example), you can harden the finished piece by heating it to increase its hardness. See our handy how to heat-harden silver tip for more information about this.

We hope this helps unravel the mysteries of metal hardness. At least it may be a good start. Nothing teaches better than experience, so I encourage you to experiment with hardness. Push the envelope and try different things with different hardnesses. See what works best for the work you’re doing and pieces you’re creating. And let us know what you discover—we love learning from your experience, too!

Source: Rio Grande