Reducing the Carbon Footprint of Natural Diamonds

What is the natural diamond industry doing to reduce its carbon footprint and protect biodiversity?

The natural diamond industry has set out on its journey to decarbonize in line with global climate targets. As part of their carbon reduction strategies, NDC members are developing renewable energy projects, often in developing countries where it is harder to source energy, as well as engaging in carbon offsetting projects and investing in programs to sequester carbon.

Companies like De Beers Group are committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2030 and Rio Tinto has set the goal of achieving net zero emissions by 2050. NDC members are also involved in unique programs to sequester carbon such as by using kimberlite, the rock where diamonds are found or through various nature-based solutions.

The natural diamond world protects the biodiversity of an area almost four times the land they use, equivalent to the size of New York City, Chicago, Washington and Las Vegas combined. As much as 99% of the waste from diamond recovery is rock and 84% of the water used in diamond recovery is recycled. The natural diamond industry abides global environmental standards and stringent national laws.

Before a single diamond is recovered, environmental permissions must be granted by governments with a legal obligation for ongoing monitoring, reporting and closure plans.

The previous chapter sought to address misconceptions surrounding sustainability claims made about laboratory-grown diamonds. Now, we look to the natural diamond industry to explore how leading players are focusing on mapping and reducing their carbon footprint.

Factors that influence the difference in carbon emissions recorded by the industry

There are many contributing factors to the difference in carbon emissions recorded by the industry. These include mainly the availability of clean energy at mine locations, the production or yield capacity of a mine and exactly which stages of mining are included in methodologies.

It is estimated that for a 1 carat polished natural diamond, the emissions are 106.9kg CO2e in 2019 (Scope 1 and 2). This equates to driving 265 miles in a medium-sized car that runs on gasoline and driving just less than the distance between Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

How is the natural diamond industry working to decarbonize?

The natural diamond industry has set out on its journey to decarbonize in line with global climate targets. Leaders like De Beers Group have set the goal of becoming carbon neutral across their operations (Scope 1 and 2) by 2030 and are making progress, having achieved a 11% year on year reduction in energy intensity in 2021. Rio Tinto has the goal to reduce GHG emissions by 50% by 2030.

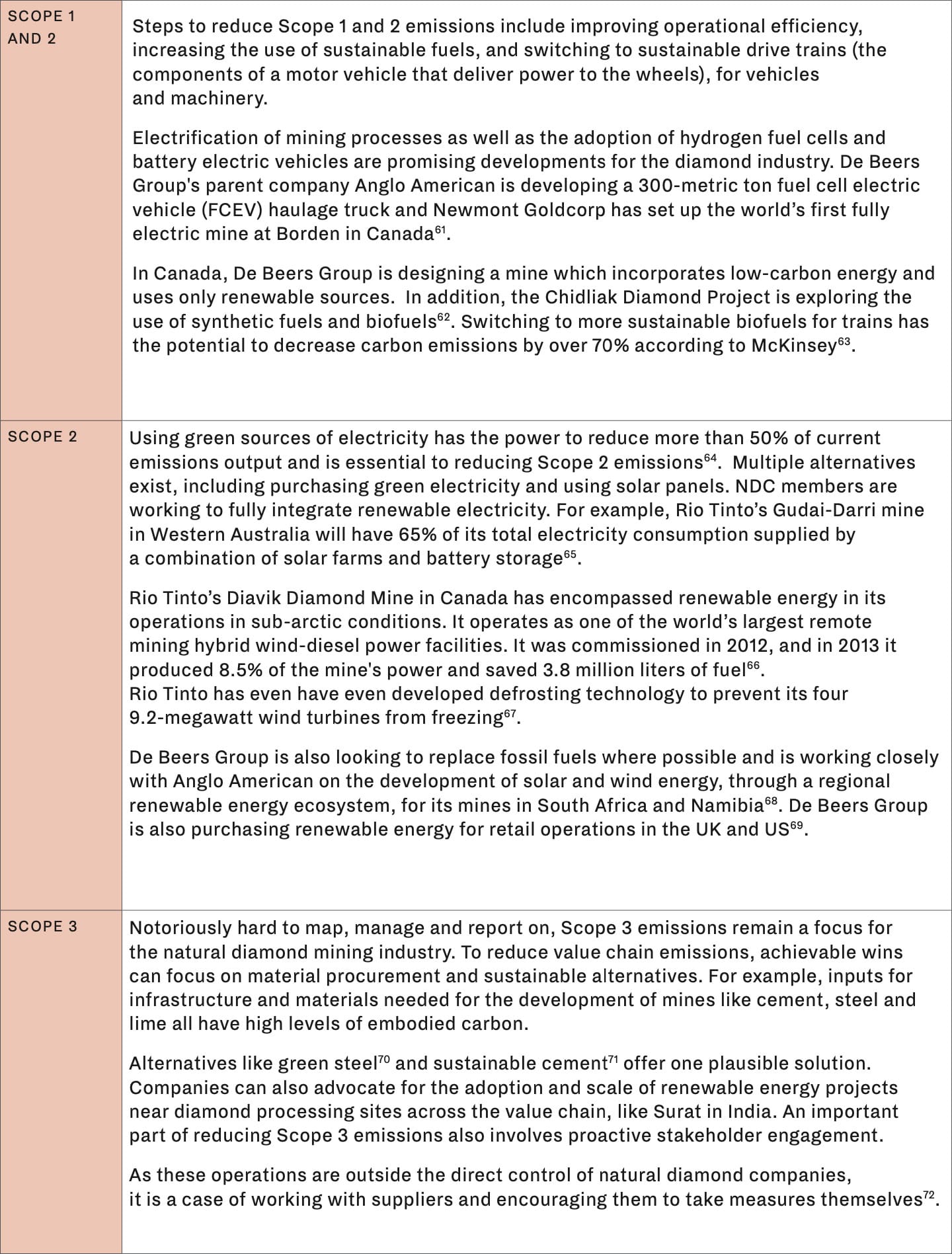

There are many opportunities for large-scale mining companies to reduce their Scope 1-3 emissions and NDC members are demonstrating progress. This section outlines how companies are working to decarbonize and where future efforts can be concentrated.

Reducing impact through carbon absorption, offsetting and conservation projects

Beyond emissions reduction strategies, NDC members are actively involved in offsetting projects and conservation efforts that help to remove carbon from the atmosphere and thus contribute to their climate goals.

Petra Diamonds is pursuing carbon sequestration initiatives. It is working with academic institutions that are exploring carbon sequestration through the mineralization of mining waste, specifically kimberlite tailings.

For the emissions that the company cannot mitigate or replace with alternative energy sources, they are engaging in offsetting projects like the Wonderbag initiative, which reinvests carbon offset financing back into communities and is verified by numerous carbon standards and protocols.

A final example is CarbonVault which is a research program supported by De Beers Group that is dedicated to exploring ways to lock away carbon in kimberlite.

What is the natural diamond industry doing to protect biodiversity?

FACTCHECK:

Members of the NDC are always working, often in partnership with governments and local communities, to reduce the impact that natural diamond mining can have on the environment. The natural diamond world protects the biodiversity of an area equivalent to the size of New York City and Los Angeles combined. NDC members protect around four times the land they use. As much as 99% of the waste from diamond recovery is rock and 84% of the water used in diamond recovery is recycled. The focus on stewardship of diamond mines by NDC members begins from the exploration phase through to the closure phase and is regulated by global environmental laws as well as national and industry regulations.

Every diamond mining operation has a different environmental impact, depending on the type of mining involved – whether it is alluvial, beach, marine or pipe mining. Equally, it is important to distinguish between artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) and modern large-scale diamond mining when discussing the environmental impact. ASM represents 10-15% of the natural diamond market and refers to mining by individuals, groups or cooperatives that often take place in the informal sector of the market. There is often less data available on details of the ASM sector’s footprint. They may be less held to account on regulations and reporting standards These smaller organizations that are publicly listed companies.

There are numerous operational measures being taken to mitigate and reduce the impact on the environment. This includes conservation efforts, rewilding projects as well as waste and water management.

Information surrounding diamond recovery processes provided by NDC members details that because no chemicals are used in the extraction process, it does not cause any irreversible damage on the environment. What it does change is the landscape as it creates waste rock piles, however these are reclaimed by the landscape as part of mine closure plans which are done under the strict supervision and approval of local communities and governments. Topography is not the same as damage. Land can be restored to land use acceptable to the local community.

In recent years, there has been an important focus on water recycling. During the diamond mining process, members consume water from sources on-site including surface water, ground water and third-party supply. As diamond recovery is reliant on a mechanical crushing process, water is more suitable for recycling and reuse. Large- scale mining companies are working to reduce their dependencies, especially in water-scarce regions, by promoting the use of water recycling. For example, in 2022 Petra recorded that their water recycling initiatives had resulted in 80% of water used being recycled on site. Lucara Diamond has also set an overarching goal of ‘zero discharge’ operations, to engage and share data with neighboring agricultural water users and to provider surplus water from their pit84.

What is the industry doing about the waste from mining?

Over 99% of waste produced by NDC members is rock, which is disposed of on-site and eventually reclaimed as part of the landscape during the mine closure and rehabilitation. De Beers Group separates waste at the source across a variety of materials ranging from metals, glass and plastic through to batteries. De Beers Group majority shareholder Anglo American has also developed a Materials Stewardship strategy to encourage waste management focused on the principles of the circular economy. Petra Diamonds recorded in 2022 that it had recycled 85% of waste from its local operations.

Large-scale mining companies recognize the value of biodiversity and ecosystem services. They employ geologists, biologists and environmental experts to develop programs and ensure all operations are in compliance with environmental regulations and that the land is managed and protected correctly. Through policy and reporting standards, the companies are committed to regular monitoring and sharing information on energy usage, air quality, vegetation and biodiversity impact.

Research conducted by environmental consultancy ERM details NDC members efforts to work towards the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 15 – Life on Land. NDC members’ protect close to four times the land they use for mining through biodiversity conservation and wildlife protection. At a significant 2,020 square km, the size of the land conserved for biodiversity is equivalent to the size of the total area of New York City and Los Angeles. It is also comparable to the size of four cities, New York City, Washington, Chicago and Las Vegas combined (1,912 square km).

Here are some examples. Each De Beers Group operation that is active has a biodiversity management plan in place. The company notes that several of their operations measure compliance against the TSM biodiversity protocol, an industry-led voluntary certification program developed by the Mining Association of Canada.

An example of successful land protection is The Diamond Route, a network of eight conservation sites established by De Beers Group. The network spans over 722 square miles of critical habitats in South Africa and Botswana. In addition to protecting endangered wildlife, The Diamond Route creates unique learning opportunities for students, scientists and academics.

Another case is the De Beers Group Moving Giants initiative, which aims to safely translocate elephants with the Peace Parks Foundation to find them safe homes and secure their future in Mozambique.

Other examples include Petra Diamonds, who have funded a four-year BirdLife Africa Secretarybird project on an endangered bird species. This resulted in the publication of a scientific article on the feeding and breeding of the bird species.

Petra Diamonds has also started a bee pollinator conservation project where bees are removed from the mining site and placed in a safe environment. Operational sites have trained beekeepers to place bees in well secured hives.

Both Rio Tinto and Arctic Canadian Diamond Company manage Wildlife Monitoring Programs. Similarly, RZM Murowa have a strict relocation program of crocodiles and pythons with the support of the local Parks and Wildlife Authority. Lucara Diamond are driving a research project with BirdLife Botswana to assess the impact of mining on insects and birds. They also have plans to drill a borehole for a plantation area where the community can cultivate plants to use in basket weaving and other projects.

Regulations and planning for a positive mining legacy

NDC members are focused on creating a sustainable legacy and going above and beyond regulatory and environmental compliance. All members have to comply with international and environmental legislation aligned with standards including ISO 14001, which provides a framework for effective environmental management systems. This runs alongside reporting requirements in line with the GRI Mining and Metals Sector Supplement and other corporate sustainability reporting guidelines and frameworks.

The stewardship of mines throughout their life cycle underscores the strict rules that mining companies must follow, related to both post- mining land use and economic plans to support the socio-economic prosperity of communities. Permits are not provided without details of impact mitigation, a sophisticated closure plan and proof of financial resources to support a sustainable exit.

A mining closure plan involves how a site would be managed at the end of its productive life, the activities to achieve closure goals and how the land can be rehabilitated.

In an interview, a representative from De Beers Group noted that “We need to be planning for closure right from the design of the mine.”, which is what the large-scale mining industry is doing.

The Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals & Sustainable Development outlines closure plans should include stakeholder engagement, risk analysis, close monitoring and maintenance as well as financial assurance and many other areas.

Varying geographies have a range of regulations pertaining to environmental mining regulations and closure plans. For example, in Canada there is the Canadian Environment Protection Act administered by the Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC).

According to Ryan Fequet, Executive Director for the Wek’èezhìi Land and Water Board, the Northwest Territories (NWT, Canada) have Land Claim Agreements and a unique, progressive and empowering piece of legislation called the Mackenzie Valley Resource Management Act. This ensures a transparent, holistic and integrated approach to renewable and non-renewable resource management. Regional Land and Water Boards of the Mackenzie Valley support in the licensing on everything from water use and wastewater management to land use. These licenses have strict reporting and monitoring requirements too. Further expansion of their policies and guidelines can be found in the Annex.

Additionally, in Canada there is the Mining Association of Canada’s Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM) standard that supports mining companies in managing key environmental and social risks. With this standard, an independent board completes an environmental assessment and also uses tools like Socio-Economic Agreements. A SEA sets out commitments and predictions made by a company regarding their impact. This is then monitored and published in a yearly report to the Government of the Northwest Territories.

In South Africa, regulations over mining begin at the scoping phase all the way through to closure. As of 2010, mining became a listed activity. The environmental provisions of the National Environmental Management Act (NEMA) No. 107 of 1998 now apply to mine closure certification resulting in mines having to comply with stipulations of this Act too before qualifying for closure. NEMA underlined that public consultation is essential at the early stages of projects.

Elsewhere in Australia, the Government of Western Australia Department of Mines and Petroleum (2017) Mining Rehabilitation Fund – Guidance and The Mining Rehabilitation Fund (MRF) Act of 2012 approach important issues related to funding the closure and rehabilitation of abandoned mines. This goes against the narrative that mining companies simply enter a region and leave with no accountability.

IN FOCUS: MINING REGULATIONS AND GUIDELINES

Whilst not an exhaustive list, the list below details initiatives, guidelines and frameworks which highlight the level of regulation on opening mines and closures:

- Australian Government (2016) Mine Closure – Leading Practice Sustainable Development Program for the Mining Industry: introduction to mine closure and current leading practices from an Australian perspective.

- ANZMEC (2000) Strategic Framework for Mine Closure

- ICMM (2008) Planning for Integrated Mine Closure – A Toolkit: provides a broadly conceived life cycle and risk-based approach to closure planning.

- Mining Association of Canada (2008) Towards Sustainable Mining – Mine Closure Framework: an industry-led initiative to articulate the commitment of member companies to promote responsible mine closure.

- NOAMI (2010) Policy Framework in Canada for mine closure and management of long- term liabilities

- World Bank Multistakeholder Initiative (2010) Towards Sustainable Decommissioning and Closure of Oil Fields and Mines:provides a policy-oriented series of toolkits related to closure for both oil fields and mines.

- Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development (IGF) (2013) The IGF Mining Policy Framework: Mining and Sustainable Development: lays out a framework which provides a comprehensive model for policy that will allow mining to make its maximum contribution to the sustainable development of developing countries.

Responsible mine restoration

With the closure of Argyle in Australia – one of the world’s most iconic natural diamond mines – responsible mine restoration has come into focus. It takes on average 10 years to open a mine. Having a closure plan is a prerequisite to opening a mine, in addition to social and environmental impact assessments which are audited, approved and monitored by governments and local community.

Source: Natural Diamond Council