How Diamonds Empower Botswana

On March 1, 1967, a team of prospectors led by Manfred Marx, a young South African geologist who had been combing the Central District of the newly independent state of Botswana, finally hit paydirt. A soil analysis indicated that they had chanced upon diamondiferous kimberlitic ore.

It was a discovery that may never had happened.

For 10 years already, De Beers had been searching for diamonds in British-ruled Bechuanaland, as Botswana was known before independence, but with little success. It had planned to end the project by the end of 1966, but a discovery that same year of two kimberlite-like intrusions – which ultimately were judged to be lamprophyres and devoid of diamonds – had provided the project leader, Dr. Gavin Lamont, with sufficient ammunition to successfully argue for an extension of the expedition for several more months.

It was a fortunate stroke of luck, because following the Marx team’s original find on March 1, further sampling produced more positive results, leading to the announcement on April 25, 1967, of the discovery of 2125A/K01, Botswana’s first confirmed kimberlite pipe.

It would eventually become the giant Orapa mine, and transform both the diamond industry and the country in which it was located.

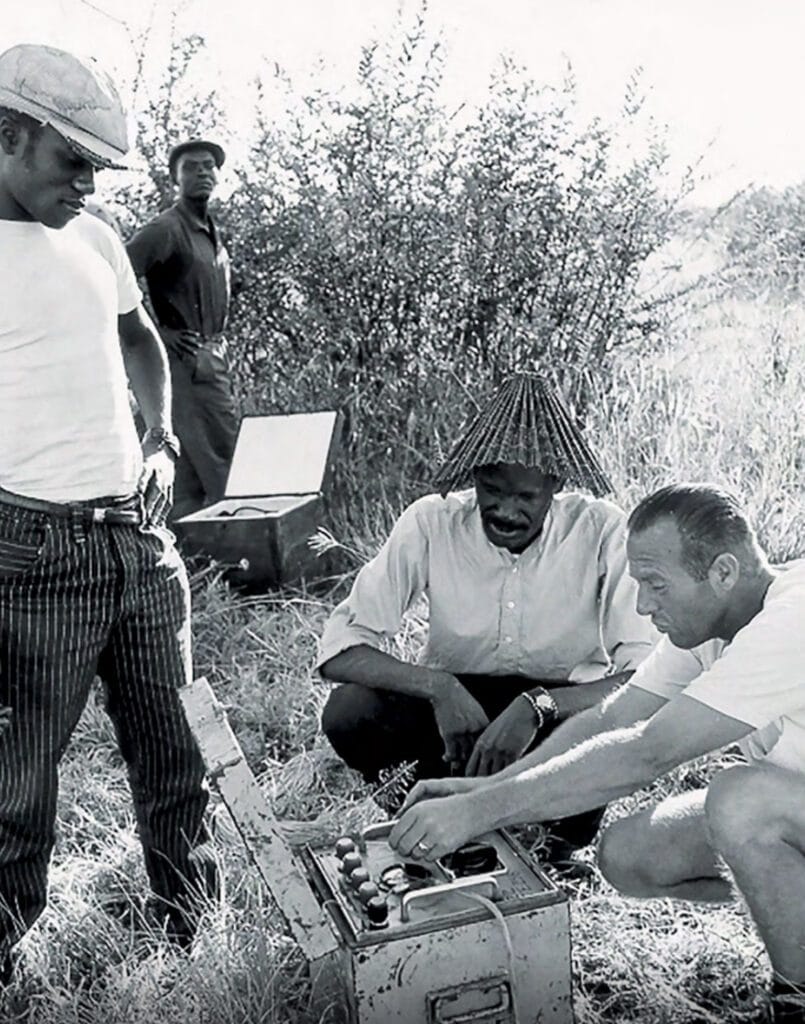

A De Beers prospecting team at work in Botswana during the 1970s. (Photo: De Beers)

A De Beers prospecting team at work in Botswana during the 1970s. (Photo: De Beers)

A dramatic transformation

Landlocked and about the size of Texas, when Botswana achieved independence from Britain on September 30, 1966, it was rated was one of the sixth poorest states in the world. The average annual income per capita then was 60 Pula, or less U.S. $80. It also was in the midst of one of the worst droughts in a century, with nearly one-fifth of its 575,000-strong population dependent on government rations.

Botswana’s economic infrastructure in 1966 was minimal. The colonial period had provided some railway lines, but only 12 kilometers of paved road. There about 40 locally born citizens who were university graduates, and about 100 with secondary school leaving certificates, of which only 16 were capable of pursuing higher education.

But 57 years later Botswana’s fortunes are dramatically different. With its population now standing at 2.36 million, it is the country with the longest democratic tradition in Africa, being the only state on the continent to have held regular free and fair elections with universal suffrage since it achieved independence.

The Botswana capital of Gaborone. Once a dusty village, construction of the city that today is one of Africa’s most important business centers began in 1964, shortly before the country gained independence.

The Botswana capital of Gaborone. Once a dusty village, construction of the city that today is one of Africa’s most important business centers began in 1964, shortly before the country gained independence.

In fewer than six decades, Botswana was transformed into an upper-middle-income country with a GDP per capita of more than $18,300, the sixth highest in Africa. It ranks at the top of the Human Development Index in Sub-Saharan Africa and has the lowest corruption ranking on the continent.

Botswana today has a road network of about 32,000 kilometers, of which 20,000 kilometers are paved, including 134 kilometers of highways. Adult literacy is close to 90 percent, among the highest rates in Africa, and some 87 percent of school-aged children are enrolled in an educational framework. The country is home to seven institutions of higher learning, of which the largest, the University of Botswana, has about 15,500 students.

Political stability and sound economic management

The serendipitous discovery of massive diamond resources, just months after achieving independence, and then the partnership that developed between the Botswana government and De Beers, were in many respects the most important factors that set the nation apart from most other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, turning it into the poster child for diamond development.

Today, while the diamond industry provides only 4 percent of direct employment, it accounts for about 30 percent of the country’s GDP and 85 percent of export income.

But Botswana’s success in managing its lucky break was never a foregone conclusion. As a former Botswana president, Festus Mogae, said in 2005: “Natural resources, no matter how lucrative, cannot develop a country without political stability, sound economic management and prudent financial husbandry.”

Botswana’s almost unparalleled rate of development was the result of a number of factors, one of which most certainly was the practical and far-sighted policies of all its governments since 1966.

Careful planning and the investment of diamond resources in infrastructure and human capital development was a feature of government policy right from the beginning. Six-year National Development Plans were fastidiously honored, and they directed revenues from diamond mining to investments in water and transport infrastructure, education, healthcare and social services.

The groundwork had already been prepared in 1967, the same year that the first diamondiferous kimberlite pipe was discovered, when the new Botswana parliament passed the Minerals and Mining Act and the Tribal Territories Act. What the two pieces of legislation did was to vest all minerals rights to the state, ensuring that the central government would maintain a degree of control over its fledgling mining sector. Before then sub-soil land rights were complicated, with some belonging to different tribes, and certain lands that had been held by Britain having already been ceded to international mining companies.

Young Botswana university graduates. Whereas at independence there were only 40 locally-born citizens with university degrees, the country is today home to seven institutions of higher learning.

Young Botswana university graduates. Whereas at independence there were only 40 locally-born citizens with university degrees, the country is today home to seven institutions of higher learning.

A diamond mining juggernaut

Following the discovery of the Orapa deposit, the Botswana government and De Beers established a joint mining company called Debswana, with the government receiving a 15 percent equity stake and a 50-50 split of profits, as well as a royalty based on production levels. All output would be sold through De Beer’s London-based Central Selling Organization (CSO), which then distributed more than 90 percent of diamonds reaching the world marketplace.

Orapa came on stream in July 1971, and would develop into the largest open-cast diamond mine in the world, with its resource consisting of one volcanic pipe that separated into two distinct pipes. Eventually producing an average of 10 million carats per year, the pit is expected to reach a depth of 350 meters by 2026.

Around the same time as the discovery of Orapa’s second pipe, two smaller kimberlite pipes were found at Letlhakane, a village about 30 kilometers to the southeast. It would come to produce only 540,000 carats per year, but contained more gem-quality diamonds than the larger mine.

The open-pit diamond mine at Orapa, with its processing plant above, on the horizon. (Photo: De Beers)

The open-pit diamond mine at Orapa, with its processing plant above, on the horizon. (Photo: De Beers)

Two Debswana employees looking over the processing facility at Jwaneng, the world’s richest producing diamond mine. (Photo: De Beers)

Two Debswana employees looking over the processing facility at Jwaneng, the world’s richest producing diamond mine. (Photo: De Beers)

When De Beers approached the government in 1974 with a request to develop the mine at Letlhakane, the state activated a clause in the previous contract that allowed it to re-open negotiations. In the agreement that followed, Botswana’s stake in Debswana rose to 50 percent, where it still stands today, and the total share of profits increased from 50 percent to 75 percent.

In 1977, De Beers discovered a massive kimberlite field at Jwaneng, about 125 kilometers west of the Botswana capital of Gaborone. It eventually would become the world’s richest diamond mine.

Becoming fully operational in August 1982, Jwaneng is Debswana’s most lucrative asset, due to the substantially higher dollar per carat rate obtained for its gems. It contributes between 60 and 70 percent of the company’s total revenue.

Mining at Jwaneng is currently at a depth of about 452 meters and its underground extension is expected to reach 816 meters by 2034.

Debswana’s fourth mining operation, Damtshaa, is made up of four small diamond pipes discovered between 1967 and 1972 in an area 20 kilometers east of Orapa. Coming on stream in October 2003, they were managed, along with Letlhakane Mine, from Orapa, and were forecast to yield 5 million carats over a 31-year projected life span.

Damtshaa is currently mothballed. The decision to halt operations was taken at the height of the COVID epidemic.

Debswana is not the diamond mining company operating in Botswana. The Canadian-headquartered Lucara Diamond Corporation owns and operates the Karowe diamond mine, less than 20 kilometers from Letlhakane. In production since 2012, it is known as one of the world’s foremost producers of large, high quality, Type IIA diamonds in excess of 10.8 carats. They include the 1,758-carat Sewelô, the 1,109-carat Lesedi La Rona and the 813-carat Constellation.

The open-pit at Debswana’s Damtshaa mine, which was mothballed during the COVID crisis. (Photo: De Beers)

The open-pit at Debswana’s Damtshaa mine, which was mothballed during the COVID crisis. (Photo: De Beers)

The 1,758-carat Sewelô diamond, extracted at Lucara Diamond Corporation’s Karowe mine. (Photo: Louis Vuitton)

The 1,758-carat Sewelô diamond, extracted at Lucara Diamond Corporation’s Karowe mine. (Photo: Louis Vuitton)

Moving the center of gravity from London to Gaborone

In July 1987, at the tail-end of a prolonged crisis in the diamond markets, De Beers purchased a large stockpile of diamonds from Debswana. In return, Botswana received a combination of stocks and cash equal to 5.2 percent of the outstanding shares of De Beers, and the ability to name two members to the world’s most important diamond corporation’s board of directors.

It was a foothold that Botswana would grow considerably in 2001, when De Beers was transformed – from a publicly listed company, with its shares traded on the New York, London and Johannesburg stock exchanges, into a privately-held concern. The new owner was an enterprise called DBI, in which Botswana held a 15 percent stake, with 45 percent being owned by the Anglo American Corporation and 40 percent by the Oppenheimer family. The Oppenheimers would eventually sell their share to Anglo American.

Thus began a process by the which the center of gravity in the rough diamond business would eventually shift, from London, where the administrative and sales headquarters of De Beer and Anglo American were located, to Gaborone in Botswana.

A student learning rough diamond sorting and evaluation skill, at the De Beers Global Sightholder Sales Academy in Gaborone. (Photo: De Beers)

A student learning rough diamond sorting and evaluation skill, at the De Beers Global Sightholder Sales Academy in Gaborone. (Photo: De Beers)

In May 2006, at a ceremony in Gaborone to mark the renewal of Debswana’s mining licenses, it was announced that De Beers and Botswana would be establishing the Diamond Trading Company Botswana (DTCB,) a 50-50 partnership, which would sort and value all Debswana’s diamond production in the country, part of which would be cut and polished locally.

A little more than five years later, in September 2011, the government of Botswana and the De Beers Group declared that, as part of a new 10-year contract for the sorting, valuing and sales of Debswana’s diamond production, De Beers would transfer by 2013 its London-based rough diamond sales activity to Botswana, transforming the African country into one of the world’s leading diamond trading and manufacturing hubs.

The 2011 agreement also provided for an independent sales outlet for the Botswana Government. To manage the sale of this supply, the parastatal Okavango Diamond Company (ODC) was set up in Gaborone in 2012. Its first chairman was Jacob Thamage, who in 2022 would serve as Chair of the Kimberley Process.

ODC kicked off operations with a 12 percent allocation from Debswana production, and started receiving 15 percent in 2016. In 2020 its allocation was increased to 25 percent.

This was increased further in July 2023, when De Beers and the Botswana Government reached an agreement in principle on renewing their rough diamond sales agreement for another 10 years through to 2033. As part of the agreement, the share of Debswana supply sold through ODC would be increased immediately to 30 percent of run of mine production, and that share would grow progressively to 50 percent by the final year of the contract. The parties also agreed to a 25-year extension of Debswana mining licenses until 2054.

Delivering the benefits of a diamond economy

Speaking after the signing of the 2023 sales agreement, De Beers CEO Al Cook said that the new deal “represents our commitment to deliver investments in Botswana’s diamond production, Botswana’s diamond value chain, Botswana’s knowledge-based economy and, above all, the people of Botswana.”

The country is a now very much a powerful and independent force in the diamond sector, and a leader in its own right.

That status was further enhanced in 2022, when the Kimberley Process Plenary, meeting in the Botswana capital, approved the candidacy of Gaborone to be the host of the KP Permanent Secretariat. Terms of reference and a country-host agreement, negotiated by a special task force chaired the World Diamond Council, were approved at the 2023 KP Plenary at Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe.

The KP Permanent Secretariat is to begin operations in Gaborone during 2024.

But the government is determined to leverage the country’s diamond wealth so as to expand its economic base beyond rough diamond mining. In fact, a feature of the 2023 sales agreement with De Beers was a commitment by the company to invest up to U.S. $750 million over the coming decade in a fund designed to accelerate the diversification of Botswana’s economy.

It’s a process well illustrated by the Diamond Technology Park, which has sprung up nearby Gaborone’s international airport, adjacent to De Beers’ headquarters in the city. It houses a growing community of diamond manufacturers, gem labs and other service providers. It’s also home to the Botswana Innovation Hub, which is intended to be the cornerstone of a national program supporting the growth of technology-driven research and entrepreneurship.

Gaborone’s Diamond Technology Park, providing facilities to the city’s growing community of diamond manufacturers, gem labs and other service providers.

Gaborone’s Diamond Technology Park, providing facilities to the city’s growing community of diamond manufacturers, gem labs and other service providers.

Source: World Diamond Council