History of Diamonds In Engagement Rings

Jack Ogden FGA takes a look at the history of diamonds being used in engagement rings. You might be a little surprised at how far the custom dates back.

Here is a question for you. Read this sentence about engagement rings: “As for the engagement ring, modern fashion prescribes a diamond solitaire, which may range in price from two hundred and fifty to two thousand dollars.” When do you estimate that was written? Before or after World War II?

A casual drift around the internet or a glance through the glossies might give you the idea that De Beers somehow invented the diamond engagement ring back in the mid-1900s, or, if they didn’t invent it, then they put their marketing muscle behind an existing but not common practice. The truth is that the sentence above appeared in the book Manners and Social Usages written by Mary Elizabeth Wilson Sherwood, published in New York in the 1880s. There are plenty of other references to diamond engagement rings in that era.

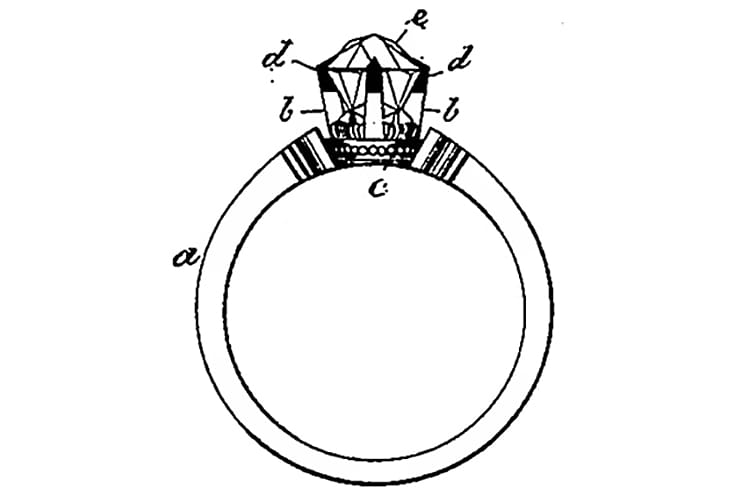

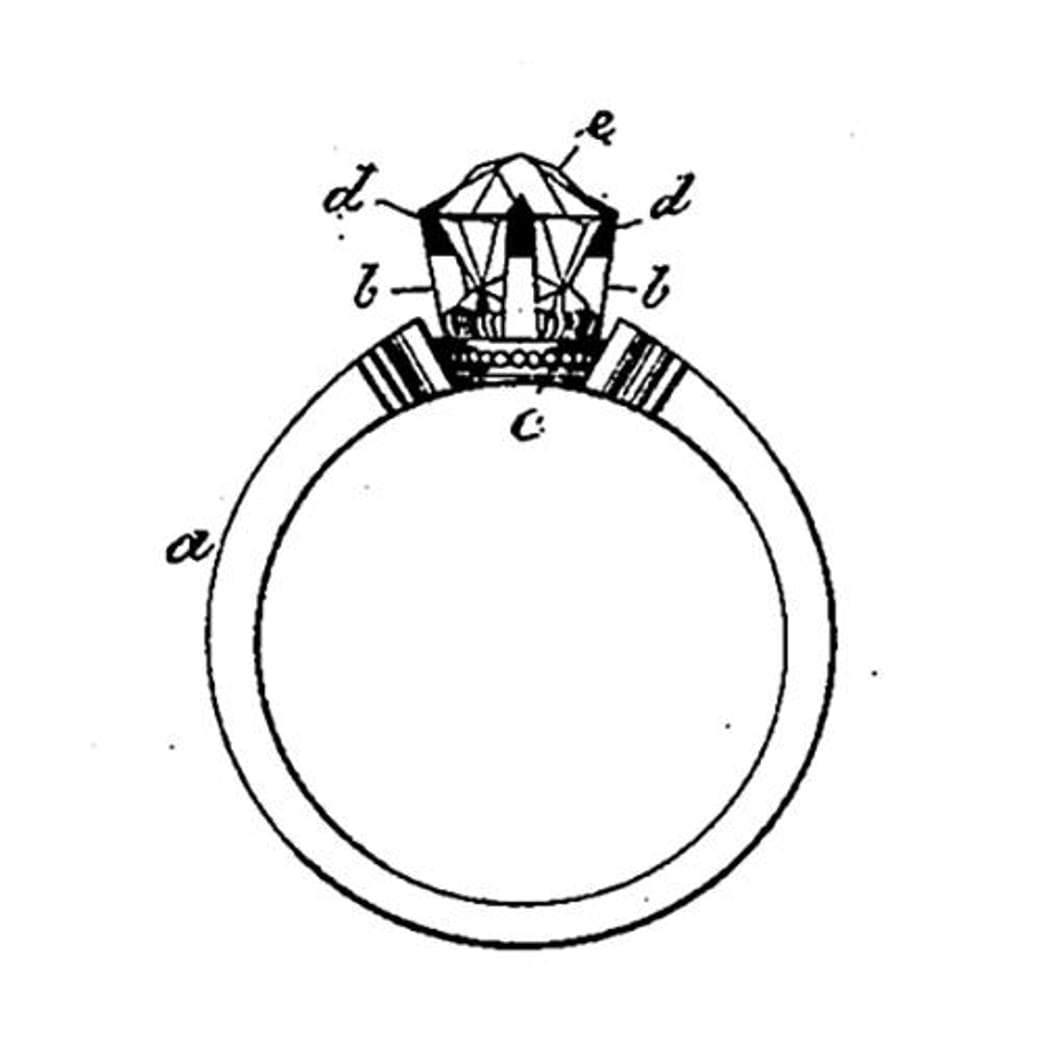

A few years before that book was written we are told that a solitaire was the typical engagement ring in the SA – in Britain a diamond-set gypsy ring was favored. For men too poor to afford a diamond ring, a broad gold band was recommended. Below is a drawing of a diamond solitaire ring from an 1870s US Patent – the new idea in the patent was platinum-tipped prongs.

Drawing of a diamond solitaire ring from an 1870s US patent

How far back we can trace the use of diamond engagement rings really depends on what we mean by ‘engagement ring’. The first use of the term ‘engagement ring’ I have found so far dates from 1812, so to look back before that we need to consider diamond wedding rings and diamond betrothal rings.

As this is a gemological publication we can start by noting that in 1652 an early English writer on gemstones, Thomas Nichols, wrote rather charmingly that the hardness of diamond meant that it could “be used symbolically as a signification of constancy” – that is 300 years before De Beers first said that a diamond was “forever”. The 1600s provide several examples. A diamond ring plays a part in the 1613 short story The Two Damsels by Miguel de Cervantes – best known for Don Quixote.

The ring is described as being engraved with the words ‘Marco Antonio is the husband of Theodosia’. A few years later another well-known author, Molière (real name Jean-Baptiste Poquelin) wrote a play called The Forced Marriage in which a man seeks to buy a diamond ring for his intended spouse. Even Samuel Pepys referred to a wedding ring set with diamonds in 1668. Below is the image of a man presenting his intended with a ring dates from 1514. Unfortunately it is not clear what type of ring it is, but it may well have been intended to be diamond – they were so used back then.

A frequent contender for the first diamond betrothal ring is a ring with the bezel in the form of an ‘M’ now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. This is often said to be Mary of Burgundy’s betrothal ring – she married Maximilian I of Austria in 1477. It is a photogenic ring, but there is no evidence that it was really her betrothal ring, but we do know that a diamond ring played a part in the nuptials.

As a young girl, we are told, Mary was ordered by her father to send a diamond ring to Maximillian’s father as a promise that she would marry him. An engagement ring of sorts I suppose, but it was sent to the father of the groom. Besides, an arranged marriage of a child bride is perhaps not a connotation with which the modern diamond industry would wish to associate.

There are other examples of diamond rings associated with marriage in Italy in the 1400s, for example, at the marriage of Constanzo Sforza and Camilla D’Aragona in 1475. In the British Museum there is an Italian gold ring set with a diamond with the inscription Lorenzo a Lena Lena – presumably meaning that Lorenzo gave it to his love Lena Lena. But we can’t let Italy take all the glory for early diamond set wedding or betrothal rings. In 1417 in England a woman called Johanna Fastolf died. Her Will mentions a diamond-set ring engraved Vous aime de tout moun coer (‘[I] love you with all my heart’). It is tempting to assume that this must have been her wedding ring.

With other medieval diamond rings and those from the Roman period, there is no way to establish whether they were connected with marriage. We know it was the practice for the Roman man to give his intended a ring, and sometimes the other way round too. Many such rings survive, some identifiable by their design, others by inscriptions. The Roman writer Ovid mentioned a man sending a ring to his beloved with some rather unsubtle (and unprintable here) double meaning.

We don’t have a picture of Ovid, but when the Nuremberg Chronicle was printed in 1493 it had a little image of Ovid holding a ring – probably in reference to this. With the coming of Christianity it all got a bit more formalized, but rings still played a part – if you could afford them. In the 300s Augustine of Hippo (a place in what is now Algeria, not the animal), later known as Saint Augustine, explained that a priest shouldn’t hesitate to marry a couple even if they were too poor to give rings to each other.

Ovid holding a ring, from the Nuremberg Chronicle

A millennium and a half after Saint Augustine, a French author similarly noted that it was surprising how many marriages were prevented for want of a diamond ring. Here however, the intention was more cynical – a reminder that it was not unknown for a man’s wealth to be a factor in attraction. History provides us with some useful gem marketing material, but also teaches us is that in some things little has changed.

Source: Gemmological Association of Great Britain, www.gem-a.com