Diamond Empowerment in Angola

The Republic of Angola is a study in contrasts. Home to the eighth largest economy on the African continent and the third largest in Sub-Saharan Africa, the country is a natural resource powerhouse, ranked as the world’s 16th largest oil producer in 2023 and its fourth largest rough diamond producer by value in 2022.

But the potential provided by Angola’s vast mineral wealth has yet to be met by its level of economic development, and that disparity can largely be traced to the country’s devastating civil war, which began when it gained independence from Portugal in 1975, and raged on all the way through to 2002. It was a conflict that led to the death of an estimated 500,000 to 800,000 Angolans, with hundreds of thousands maimed and more than 4 million people losing their homes and livelihoods.

The war eventually ended with the killing in 2002 of rebel leader Jonas Savimbi, after which the Angolan government declared a ceasefire. But, critically, the peace thereafter was largely maintained by the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme, which was launched soon after, at the start of 2003.

The KPCS prevented the military wing of UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola), the rebel movement that had been led by Savimbi, to continue financing its armed struggle against the government. According to Global Witness, between 1992 and 1998 as the war raged on, UNITA had earned at least $3.72 billion from illicitly obtained rough diamonds mined in the country. That constituted about 93 percent of all Angolan diamond sales during the period.

Indeed, when the Kimberley Process was established in 2000, Angola was considered one of the three primary sources of conflict diamonds on the world market, alongside Sierra Leone and the DRC. But it also became one of the KP’s most notable success stories.

In November 2013, barely 11 years after the end of the bloody civil war, the KP Plenary confirmed by consensus that Angola would serve as the organization’s 2014 Vice Chair. It thus assumed the post of KP Chair in 2015, and so came to head the very body that had been formed to help support its salvation.

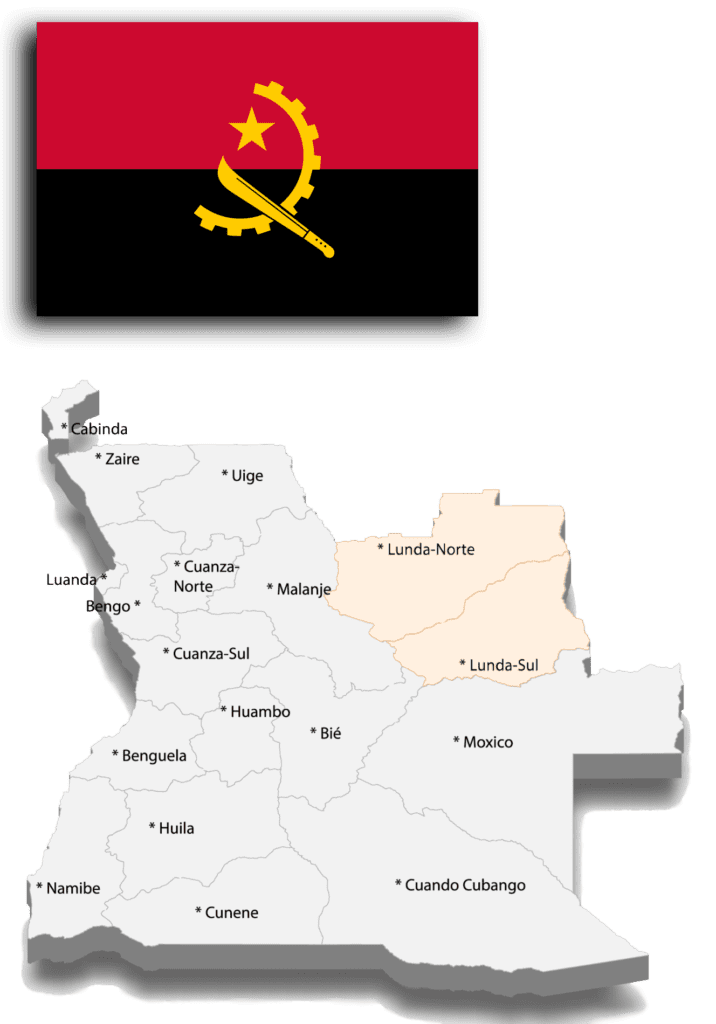

A map illustrating the provinces of current-day Angola. The diamond-rich Lunda-Norte and Lunda Sul provinces in the northeast of the country are highlighted.

The discovery of diamond deposits

The existence of rough diamonds in what eventually would become Angola was first recorded as way back as 1590, only 15 years after the territory was declared a colony of the Portuguese Empire.

But the discovery of viable diamond deposits can be traced to 1912, when an American company prospecting in the Congo decided to expand its search southward into the Lunda area of Angola. In July of that year, the first alluvial diamonds were found in tributaries of the Luembe River.

A company called Companhia de Pesquisa Mineiras em Angola (Pema) was created in Lisbon in 1913 to manage the mining of the diamond deposits, and production started in 1916. In 1917 Pema was reorganized into the new body called Companhia de Diamantes de Angola (Diamang), which within four years managed to acquire all prospecting rights to Angola, with the exception of the strip along the Atlantic coast. To date, almost the entirety of Angola’s known diamond deposits are in the northeast of the country, in what today is Lunda Norte Province, and in Lunda Sul Province to its south. Deposits also have been discovered in Malanje, Cuanza Sul and Bié provinces.

All diamonds extracted in Angola for the first seven decades of production were alluvial, coming from deposits in the Andrada and Lucapa areas of northeastern Lunda Norte and the Cuango River. Alluvial production peaked at 2.4 million carats in 1973.

Kimberlite deposits were first reported in 1952, following the discovery of the three-kilometer long Camafuca-Camazomba pipe. Many other diamondiferous kimberlites were discovered afterwards, particularly in the 1970s. But none were properly analyzed and developed, largely because of increasing guerrilla activities in Lunda Norte and Lunda Sul, eventually escalating into a full-blown civil war.

Civil war follows independence

Angola gained its independence in the wake of the Carnation Revolution in Portugal on April 25, 1974, when a military coup in Lisbon led to the overthrow of the country’s authoritarian regime. The new Portuguese government sought to divest the country of its costly colonies, and the African country became a sovereign state on November 11, 1975.

Portugal ended its 400-year rule over Angola without establishing a new government. However, one of the three main rebel armies, the Marxist-Leninist Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), which already was headquartered in the capital of Luanda, assumed power. It was an act that was internationally recognized, if not universally welcomed, for the ensuing civil war largely became an extension of the larger Cold War.

One of the first acts of the new Angolan government was to nationalize the assets of Diamang, which were transferred to the newly formed National Diamond Mining Company of Angola (Endiama), established on January 15, 1981. Diamang itself was formally disbanded in 1988.

But with the chaos that followed the onset of civil war, official production of diamonds plummeted, reaching a low of 270,000 carats in 1986. Illicit production, however, rose dramatically, and was estimated to be as high 1 million carats in 1992.

Weaponry from the Angolan civil war, which pitted rebel forces against the MPLA-led government, and continued unabated from 1975 to 2002, with brief interludes of relative calm. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The first rough diamond certificate of origin program

The biggest drain on the Angolan state’s diamond resources was UNITA, which through the 1990s operated in more than 70 percent of the country, where it had access to the rough diamonds by which it financed its activities.

An attempt in October 1994 to end the civil war, through a process called the Lusaka Protocol, fell apart when the UNITA rebel movement refused to demobilize and then resumed arms purchases. By then the Cold War had ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union, and so had apartheid rule in South Africa, whose previous government had supported UNITA. The international community was losing patience, and in June 1998 the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1173, which imposed sanctions against UNITA. Among its requirements was the prohibition of the import of diamonds not controlled through a certificate of origin scheme or the recognized Angolan government.

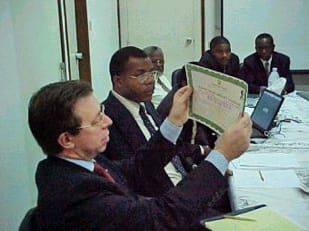

Robert Fowler, the Canadian diplomat who headed the UN committee overseeing sanctions against UNITA, sought industry support, and turned to Mark Van Bockstael, the senior gemologist at Belgium’s Diamond High Council (HRD), the predecessor of today’s AWDC. Van Bockstael would later serve as Chair of the World Diamond Council’s Technical Committee and Chair of the Kimberley Process’ Working Group of Diamond Experts on behalf of the WDC.

By September 1998 Van Bockstael was in Luanda as the newly appointed chair of the HRD Task Force on Angola. There he helped local government officials develop a forge-proof certificate of origin that would enable the country to export rough diamonds in compliance with UN sanctions. It was introduced just three months later in December 1999.

What was created was a bilateral arrangement operated by customs officials in Angola and Belgium. Each certificate issued in Angola generated an import confirmation certificate when the parcel arrived in Antwerp. This was returned to Angola to ensure that the import and export statistics from the two countries matched. Thus, was developed a system that would become a model and precursor of the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme.

Mark Van Bockstael holding up a new Angolan certificate of origin, during a meeting in the country’s capital of Luanda in December 1999. To his right is the then-Angolan Minister of Geology and Mines, Antonio C. Sumbula. Van Bockstael, who headed the HRD Task Force in Angola, later served as Chair of the WDC Technical Committee, and Chair of Kimberley Process Working Group of Diamond Experts. (Photo courtesy Mark Van Bockstael)

The opening of the Angolan mining sector

The peace agreement signed in April 2002 that brought an end to Angola’s 27-year civil war enabled the country to get its diamond industry back on track.

But, already 10 years earlier, in 1992, Angola had held its first multi-party elections for president and a national assembly. It was part of an earlier attempt to bring an end to the war. That failed to stop the fighting, but it did signal the readiness by the MPLA to move away from its doctrinaire Marxist approach to governance, and the beginning of a transition to a market economy.

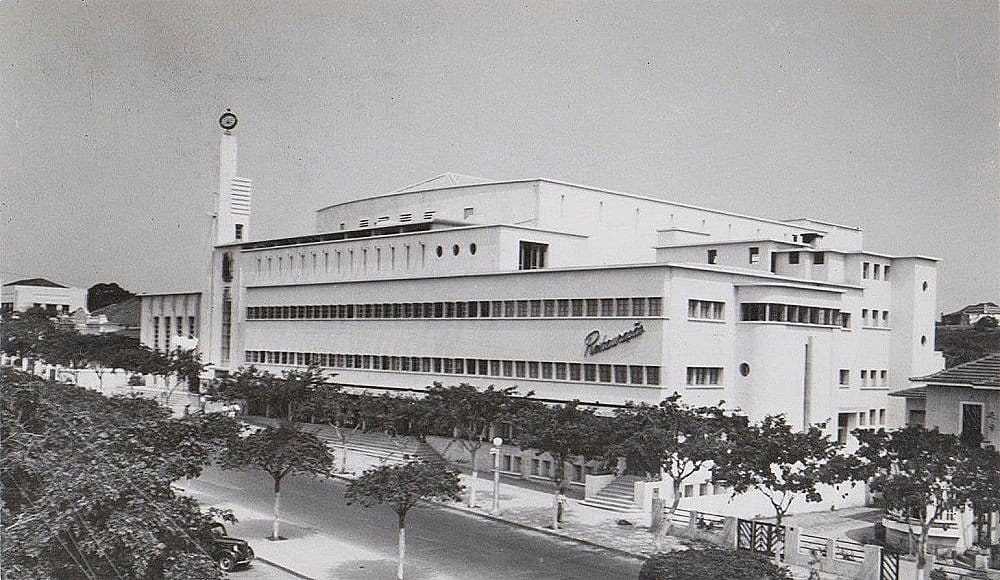

The Estúdio/Restauração Cinema building in the Angolan capital of Luanda, which served as the meeting place of the National Assembly of Angola from 1980 to 2015, where in October 1994 Law no. 16/94 was passed, enabling the state-owned Endiama mining corporation to partner with both foreign and international mining companies. This led to the opening of the Angolan diamond mining sector. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

In October 1994, the Angolan National Assembly passed Law no. 16/94, which aimed to regulate the diamond sector, attracting outside investment while ensuring that the state would receive its appropriate share of revenue. What it essentially did was vest all rights for prospecting, mining, sorting and marketing of rough diamonds in Endiama, while allowing the state-owned mining company to exercise those rights in partnership with third-party companies.

Endiama consequently entered into joint venture arrangements with a variety of international mining corporations, among them ALROSA of Russia, Odebrecht from Brazil, and Daumonty Financing, a UK-headquartered company owned by Israeli diamantaire Lev Leviev.

In 1995, Endiama signed another series of joint venture agreements with international firms, enabling them to buy rough diamonds from local diggers. These included De Beers, as well as rough traders from Belgium, Israel and the United States. Years later, De Beers would close all its buying offices in Africa because of the conflict diamond crisis.

In 1999, Endiama transferred its marketing rights to a newly created subsidiary called Sociedade de Comercialização de Diamantes (SODIAM), which in turn created a rough dealing joint venture called Ascorp, in which it held a 51 percent stake, with two foreign traders holding the remainder. All othe r rough buyers had their licenses revoked., while Ascorp served as the single export channel for Angolan rough diamond production.

r rough buyers had their licenses revoked., while Ascorp served as the single export channel for Angolan rough diamond production.

Ascorp’s contract ended in July 2004, leaving SODIAM responsible for the marketing of all Angolan production.

The development of Angola’s kimberlite mines

The full potential of the Angolan diamond industry lay in the development of its kimberlite or primary resources, which was an undertaking that required massive investments in infrastructure, equipment and training, for which Endiama would reasonably require the support of the international mining community. But before the end of hostilities in 2002, few foreign firms were ready to risk their capital or the security of their employees.

Complicating the task was the fact that, because of the civil war, Angola was most probably the most under-prospected nation in all of southern Africa, certainly when compared to diamond-mining countries like South Africa, Botswana and Namibia, and even Zimbabwe. Its potential as a rough producer was believed to be massive, but the actual extent of its resources was largely conjecture.

The giant open-pit Catoca mine, the world’s fourth largest rough diamond producing facility. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The first kimberlite mine to come on stream was Catoca in Lunda Sul. The war was still ongoing, but it managed to produce 1.2 million carats in 1998, its first full year of production. The deposit had been explored by Russian experts in the 1980s, but UNITA’s occupation of the region in which it was located made work in the area unfeasible until 1996.

When the development of the open-cast Catoca mine finally got underway, it was managed by a joint venture in which Endiama and ALROSA both held 32.8 percent of the shares, and Odebrecht held 16.4 percent.

In April 1997 Leviev also became a partner, providing the additional $25 million that was needed to complete the mine, and for which he received an 18 percent stake. He sold his share to China Sonangol in 2011.

Today, Catoca is recognized as the world’s fourth largest diamond mine, and has contributed to up to 75 percent of Angola’s total diamond output.

The development of other kimberlite mines accelerated after peace was restored to the country. These include the Lunhinga, Luaxe and Lulo projects in Lunda Norte. The country now has 14 producing mines, four of which are kimberlite operations and 10 that are alluvial.

A treatment facility at the recently opened Luele mine, which is likely to be the largest diamond mine to come on stream during the 2020s, with a projected annual production rate of 4 million carats. (Photo: CIPRA/Facebook)

Becoming the world’s third largest rough producer

On September 29, 2023, Angola’s Council of Ministers approved a National Development Plan for the coming five years. It foresaw the country reaching an annual diamond production rate of 17.5 million carats by 2027, up from the 8.76 million carats reported by Kimberley Process Statistics for 2022. This would raise Angola from the sixth largest rough diamond producer in 2022 in terms of carats, and fourth largest by value, to becoming the world’s third largest rough producer.

The 35,000 square-meter Saurimo Diamond Hub, which is located near the Catoca mine and is planned to provide facilities to cutting factories, offices, a convention center, a training school and a diamond exchange. (Photo: CIPRA/Facebook)

A key element in the plan was the coming on stream in November last year of the Luele mine, which was developed from the Luaxe project. According to industry analyst Paul Zimnisky, it will produce 3.5 million to 4 million carats annually, reaching full commercial capacity in 2025. It is likely to be the largest diamond mine to begin operations anywhere in the world this decade, and has an estimated resource of 628 million carats and a projected operational lifespan of 60 years.

Another element of the development plan is the 35,000 square-meter Saurimo Diamond Hub, located near the Catoca mine outside the town of Saurimo in Lunda Norte.

If all goes as planned, the hub will eventually house up to 19 cutting factories, offices, a convention center, a training school and a diamond exchange. Tenants that cut and polish goods locally will be eligible for tax benefits and also run-of-mine diamond supply. Its backers say it will add 5,000 jobs to the local economy, but, since it is located in a remote area about 600 kilometers from Luanda, some have questioned its economic viability.

Whatever the outcome, the past two decades have a seen a remarkable turnaround for the Angolan diamond sector, which is finally beginning to realize the true potential of its natural resources. The country is also testament to the healing capacity of the Kimberley Process.

And nine years after it served as KP Chair, the country remains an important participant in the Kimberley Process. Estanislau Buio, Executive Secretary of the Kimberly Process National Commission of Angola, today serves as Chair of the Ad Hoc Committee overseeing the three-year review of the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme, just as he did during the previous review cycle, from 2017 to 2019.

Estanislau Buio (right), Executive Secretary of the Kimberley Process National Commission of Angola, who currently is serving as Chair of the Ad Hoc Committee overseeing the three-year review of the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme, together with WDC President Feriel Zerouki, during the KP Plenary meeting in Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, in November 2023.

Source: World Diamond Council