Common Ruby & Sapphire Treatments

Rubies and sapphires are often treated to improve their colour and appearance, but what are these treatment methods, and how can gemmologists pinpoint them? Here, Gem-A Tutor Pat Daly FGA DGA talks us through some of the most common methods used for corundum.

Work is carried out on nearly all gemstones before they are offered to consumers. At the least, crystals and crystal groups are trimmed and shaped, and most stones are cut and polished to make them suitable for use in jewellery. Stones in these conditions are regarded as untreated, but a high proportion are modified in other ways to make them more attractive.

Corundum, which includes the gem varieties ruby and sapphire, is very often treated, and this is likely to have been the case for more than 1,000 years. Early treatments included dyeing and heating using charcoal fires and blowpipes. Since the 1970s, increasingly sophisticated treatment methods have been used to bring many otherwise unsaleable stones to the gem market, improving the supply of gem quality stones and making attractive, affordable stones available in commercial quantities.

Rough corundum crystals from the Gem-A Archives

Heating can now be carried out at higher temperatures than is possible with traditional methods, chemical elements may be driven into stones, and their clarity may be improved. Those who handle gemstones must know how rubies and sapphires can be treated and the clues that may inform us that they have been carried out.

Corundum Treatments: Dye

Dyes are used to add colour to low-quality corundum. Pigments suspended in oil or water are deposited in fractures and pits. Treatment is recognised by the concentration of colour in fractures and the staining of solvent-soaked swabs wiped across surfaces. In jewellery incorporating closed-back settings, coloured foil placed behind a stone usually shows some crumpling, which can be seen with a loupe.

Corundum Treatments: Heat

Heat treatment can improve colour and transparency at temperatures ranging from about 800 to 1900°C. Temperatures less than about 1000 to 1100° tend to lighten blue colours. This may be desirable to remove a modifying colour from rubies or to lighten the colours of sapphires which are too dark. There may be few clues to this relatively low-temperature treatment, but iron staining in fractures may change colour from yellowish-brown to reddish-brown.

Ruby with crystal and feather inclusions, photographed by Pat Daly.

Higher temperature treatment affects the appearance of crystal inclusions and feathers and may be easier to recognise. Colours are modified by the intensification or reduction of blue and yellow. Those colours may become more vivid, or they may be used, for example, to turn a pink stone into the more favoured pinkish-orange padparadscha colour.

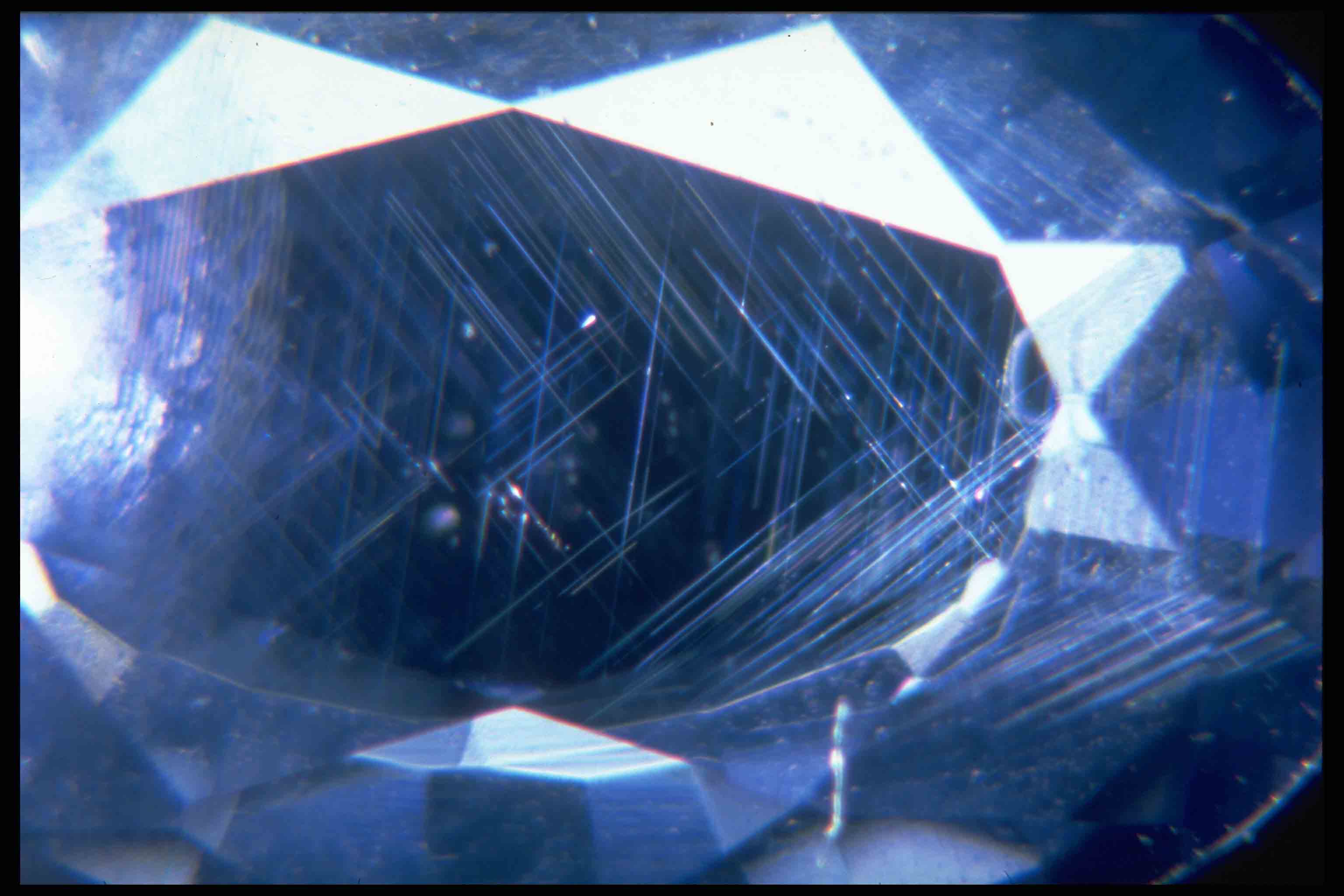

Heat treatment modifies the condition of the elements iron and titanium, which can be present as impurities in corundum. Both may combine with oxygen to crystallize as oriented needle-like inclusions. When there are enough of them, they may cause a star effect, but they can also occur as patches which reduce the clarity of stones. Heating can dissolve them so that the elements are incorporated in the corundum, and clarity is improved. These two metals interact to produce the blue colour of corundum, so this feature may be improved simultaneously.

A synthetic star sapphire, photographed by Pat Daly.

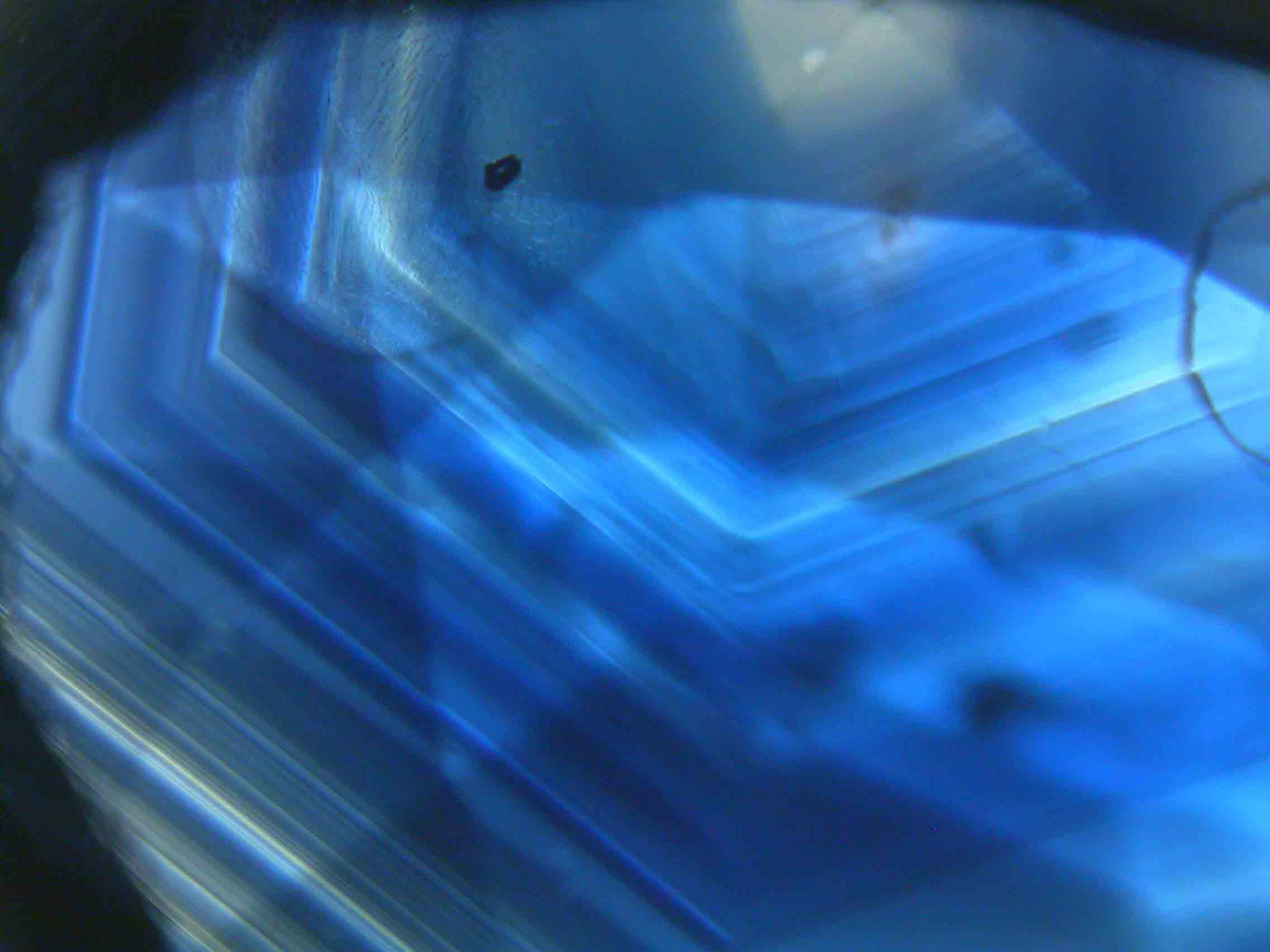

Evidence of the former presence of needles may remain as lines of tiny dot-like inclusions or of small colour patches along the directions of the inclusions. These features have been called dotted silk and cross-hatched colour zoning, respectively. Straight colour zoning, seen in most blue sapphires, becomes foggy looking, the sharp boundaries between blue and white zones becoming blurred as colouring elements diffuse short distances in response to the elevated temperatures.

Angular colour zoning in sapphire, photographed by Pat Daly.

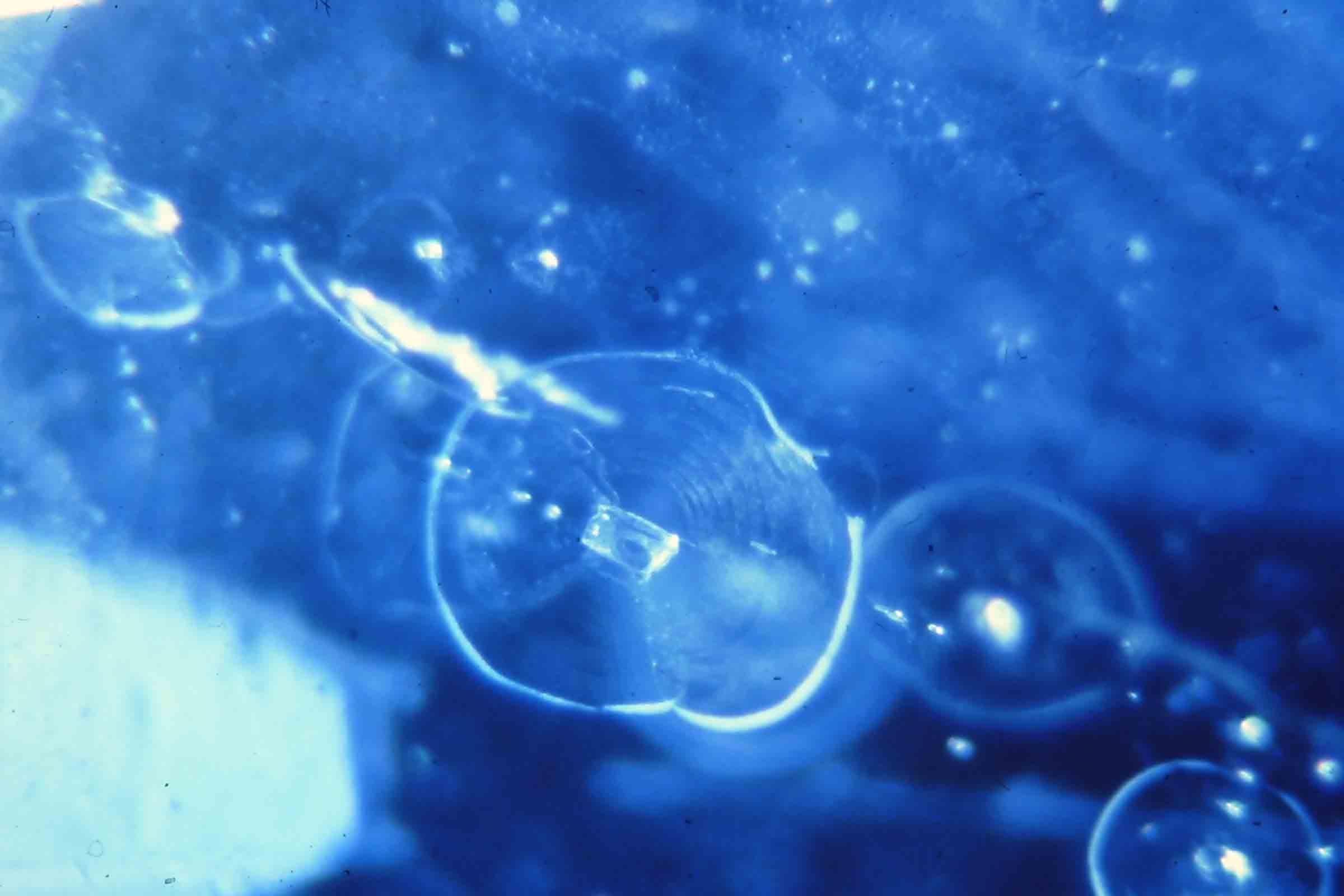

Fractures often develop around other crystals, producing features called heat discs, and when temperatures reach about 1500°, previously transparent crystals may become whitish and translucent, taking on a “frosted” appearance. Feathers, thought to represent fractures partly healed during the growth of gemstones, undergo subtle changes, but experience is needed to interpret them correctly.

Heat treated sapphire with heat disc features, photographed by Pat Daly.

Corundum Treatments: Diffusion

Colouring elements can be diffused into white sapphires, which do not improve after heat treatment. Pre-cut stones are packed in aluminium oxide containing titanium and iron and heated at up to 1850°C for some days. Colouring elements penetrate a short distance beneath the surface. Therefore, the stones must be repolished, removing some colour from the facets. When seen against diffused lighting, ideally when immersed and viewed from the pavilion side, it is usually noticed that some facets are paler than others and that colour is stronger along facet edges. Colour diffusion of chromium produces pink to red, and nickel is used for yellow stones.

Titanium may be diffused into cabochon cut stones to improve a star. Subsequent heating causes needle-like crystals to grow in three directions, and these reflect light to produce the optical effect. In most untreated star stones, needle-like crystals are seen easily with a loupe, or the straight zones in which they are concentrated are prominent features of the stone. Suspicion should be aroused when neither of these features is seen. Suitable heat treatment may improve a star without surface diffusion if there is enough titanium dissolved in a stone.

Needle like rutile inclusions in sapphire from the Gem-A Archives.

The element beryllium may be diffused further into corundum and affect the whole stone, producing a wide range of colours. The features noted above for diffusion-treated stones are not seen, and these stones may be hard to recognize, though evidence of high-temperature treatment is usually visible.

Corundum Treatments: Clarity

Heat-treating stones in contact with a flux, such as borax, may partly repair fractures. This treatment is routine for stones from Mong Hsu in Myanmar, and those from other localities may be improved by it. However, the resulting feathers are similar to natural ones; some experience is needed to separate them.

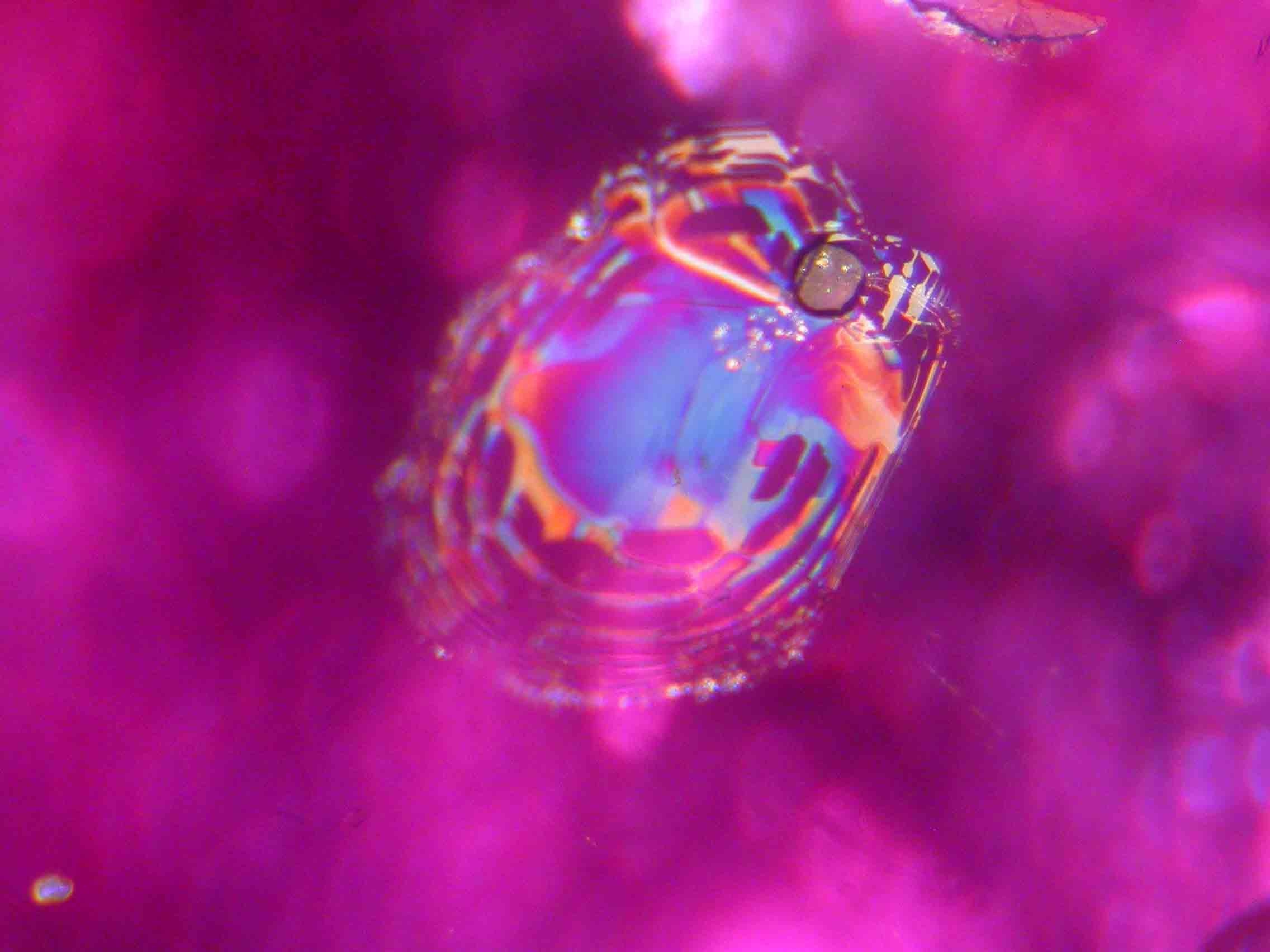

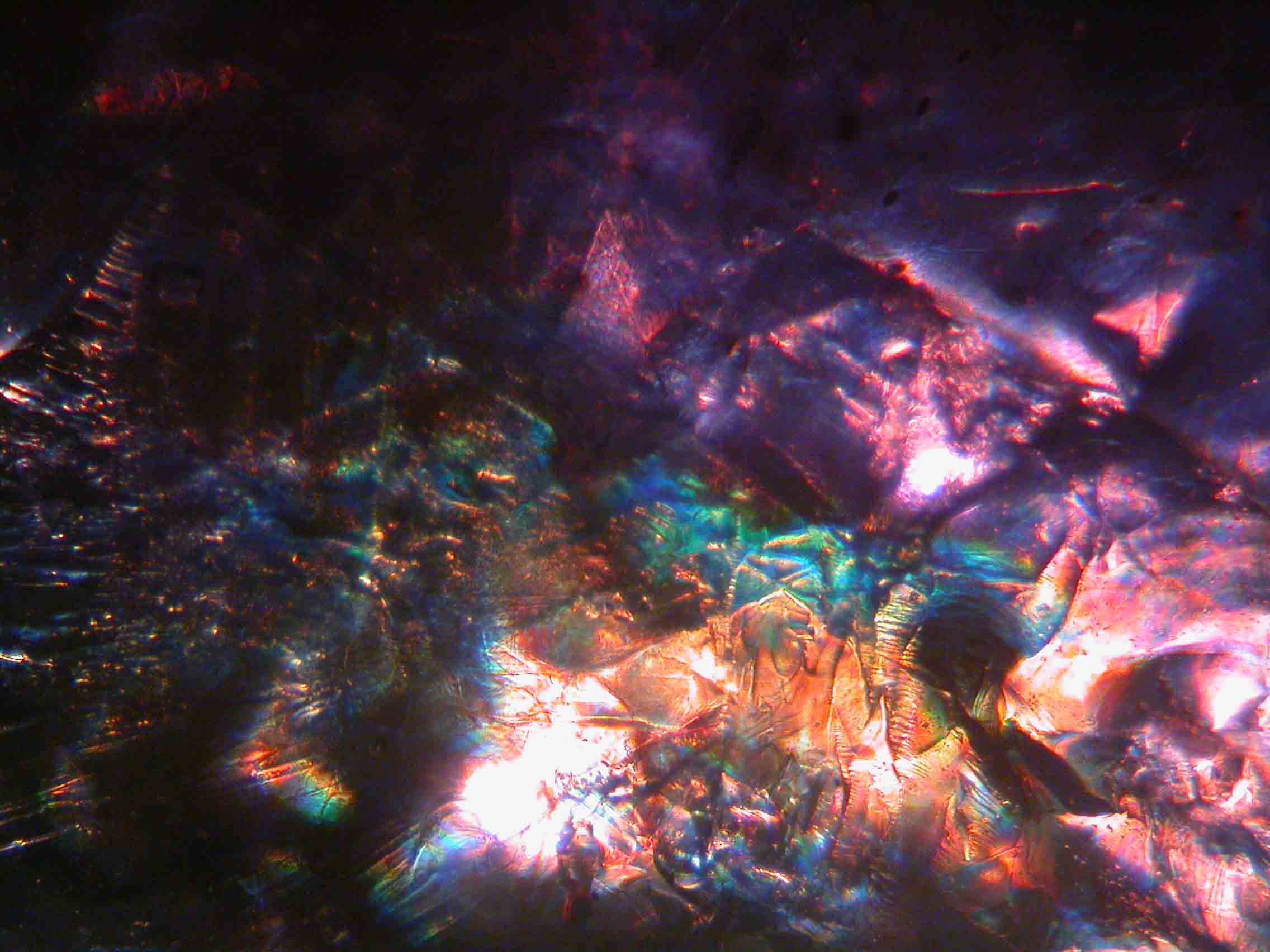

Glass-filled ruby with iridescence in direct light, photographed by Pat Daly.

Fractures in poor-quality corundum may be hidden by filling them with oil or glass. Glass-filled rubies from Mozambique are recognised by iridescence, seen in fractures at low viewing angles, and by a change of lustre when wider cracks intersect the surface. Fracture-filled stones are much less valuable than good-quality rubies, and standard workshop techniques may damage them, so it is important to identify them.

Glass-filled ruby from the Gem-A Archives.

Pale, heavily fractured corundum may be filled with glass, at least some of which is coloured by cobalt. When seen in diffused transmitted light, colour is concentrated in fractures, the stones look red through a Chelsea colour filter, and they may display a cobalt spectrum. They also show the same features as glass-filled rubies.

Corundum Treatments: Irradiation

Irradiation may produce an unstable yellow colour in sapphires. This treatment cannot be detected except by a fade test; some stones from a parcel are exposed to sunlight for some time. Naturally coloured sapphires may fade in intense artificial lighting, but the colour will usually intensify again if the stones are held in sunlight or ultraviolet.

The treatment of corundum to modify colour and/or clarity is widely practised and serves to bring stones to the jewellery trade, which could not be supplied just by using untreated stones. The improvement of gemstones by treatments is acceptable, so long as buyers are told that they have been carried out and of any issues connected with durability, such as colour fading or inability to withstand heat in workshops.

Those in the gem and jewellery trades should keep abreast of developments in this area of gemmology, pay attention to any ways that treated stones may be identified, and consider sending doubtful stones to laboratories to confirm their status.

Source: The Gemmological Association of Great Britain, www.Gem-A.com. Top image: A sapphire with abraded facet edges, photographed by Pat Daly.