Colored Gemstones from Brazil

Guy Lalous ACAM EG presents us with a historical review and an updated overview of the Brazilian colored stone industry. His latest Journal Digest from Gem-A’s Journal of Gemmology (Winter 2017. 35.8) also examines the effects of China’s emergence as a consumer market on Brazil’s gem industry. Recent information on Brazilian gem occurrences is presented from data compiled by the Brazilian National Department of Mineral Production (DNPM) and other resources.

The history of Brazilian gemstones began with the early colonisation period. No gem deposits were found until 1573 when emeralds were discovered in the present-day Governador Valadares area. In the late 17th century, the legendary gold mines of Sabarabussu were discovered, located to the east of the present city of Belo Horizonte.

The ensuing rush then expanded north, unearthing the first diamond deposits a few decades later near the town that would become Diamantina. The exploration for gold and diamonds overshadowed other gem mining activities until the 19th century, apart from the Imperial topaz deposits found nearby in the old Minas Gerais capital of Ouro Preto. During this time, the term ‘garimpeiro,’ which refers to independent miners, emerged.

Figure 1: This suite of morganite (16.69–22.22 ct) was cut from Brazilian rough. The gems were fashioned into various custom cuts, including (from upper left to lower right) Concave, Super Trillion, Deep Concave, and StarBrite. Courtesy of John Dyer; composite photo by Ozzie Campos.

Germans originating from Idar-Oberstein immigrated to the present-day state of Rio Grande do Sul and to the north-eastern part of Minas Gerais after Brazil’s independence from Portugal in 1822. During this period, Idar-Oberstein was experiencing economic troubles as the production from its agate mines dwindled.

The immigrants brought their cutting and polishing techniques with them and initiated the first stage of development for the modern Brazilian colored stone industry.

Among the most notable early finds was the 110.5 kg Papamel aquamarine, discovered in 1910 in the Marambaia Valley, as well as numerous emerald deposits. On the eve of World War II, gem-related activities in Brazil were mainly limited to mining, while the end of the war saw the widespread closure of industrial mineral mines in Minas Gerais. Many of these mines turned exclusively to gem production, and local lapidary and other trade activities grew dramatically. The latter half of the 20th century was also marked by the emergence of the Brazilian jewelry industry.

What about Brazilian Emeralds?

Emerald is the green variety of the mineral beryl, colored by chromium and vanadium. These trace elements are normally concentrated in quite different parts of the Earth’s crust, but complicated geological processes enable these contrasting elements to find each other and crystallise into one of the world’s most beautiful gemstones.

Geological Processes of Brazilian Emeralds

Brazilian emerald mineralization belongs to the classic biotite-schist deposit, formed by the reaction of pegmatitic veins within ultrabasic rocks. The granitic pegmatite injection makes the emerald crystallise at the contact zone between these chemically contrasted rocks. The pegmatite brings beryllium, while the ultrabasic rock contains chromium and vanadium, and the reaction between them is called metasomatism. This reaction is, however, only possible when geological fluids are present enough to ensure the transportation of the elements. Pegmatite-free emerald deposits, linked to ductile shear zones, are also known in Brazil (G. Giuliani).

Figure 2: Weighing 6.11 ct, this emerald is unusually large for clean material from Brazil. Courtesy of Paul Wild; photo by Jordan Wilkins.

Brazilian emerald production occurs in three states: Goiás, Bahia, and Minas Gerais. The first emerald site in modern times was discovered in 1912 in the deep south of Bahia State, near Brumado. Other emerald discoveries followed in the early 20th century at Ferros, in Minas Gerais, at Itaberaí, in Goiás, and Anagé in Bahia.

More recent discoveries include Itabira (1977) and Nova Era (1988) in Minas Gerais, at Santa Terezinha de Goiás (1981) in Goiás, and in the Serra de Carnaíba region (1983) of Bahia. Since the 2000s, Brazil has been ranked third among the world’s leading emerald producers, behind Colombia and Zambia.

Paraiba Tourmaline from Brazil

Paraíba tourmalines represented the first recorded instance of copper occurring as a coloring agent in this mineral. The blue-to-green colors are primarily due to copper (Cu2+).

Figure 3: The bright coloration shown by Paraíba tourmaline (here, 5.73 ct), as well as its rarity, have contributed to its high value. Photo and stone courtesy of Paul Wild.

Figure 3: The bright coloration shown by Paraíba tourmaline (here, 5.73 ct), as well as its rarity, have contributed to its high value. Photo and stone courtesy of Paul Wild.

Paraíba tourmaline—for its singularity and its profitability— became perhaps the most important discovery of the 20th century. Uncovered for the first time in 1987 in the São José da Batalha district of Paraíba, this tourmaline’s unique ‘neon’ blue-to-green coloration made it one of the most valuable colored stones on the global market. Production of Paraíba tourmaline has, unfortunately, dwindled in recent years.

Global Gemstone Trade – The Role of Brazil

In the late 1990s, Brazilian gems were mainly exported to the United States, Europe, and Japan, with gem exports to Hong Kong and India increasing too. Finally, another major player emerged: China. The increase in exports of rough gem material to Asia has become very significant, and, for a time, most of it was cut and polished in India and China.

Chinese brokers began to arrive in the quartz-producing areas at the beginning of the 2000s. These brokers bought most of the cheaper gems, contributing heavily to a rise in mining activities. Over the years, Chinese dealers acquired a greater variety of stones, showing a preference for tourmaline, especially rubellite.

However, one consequence of the increasing trade with China has been the collapse of Brazil’s domestic gemstone cutting and polishing industry for low-value materials. The negative effect on local economies is particularly apparent in north-eastern Minas Gerais. In Teófilo Otoni, of the 2,700 lapidary businesses operating in 1993, only 360 remained in 2005. In 2011, China was the main partner in Brazil’s gem commerce, with 2013 seeing Brazil export 60% by weight, or 25% by value, of its output to China (up to 50% by value if Hong Kong is included).

Brazil, however, still remains significant for cutting higher-value gemstones. Teófilo Otoni and Governador Valadares remain the major gem-cutting and trading centres. Various urban centres host the country’s main gem fairs, which are small venues compared with other international shows.

An important factor to note is the informal trading of gems; several hundred individuals travel around the country and acquire rough material to sell later in the metropolitan areas. The widespread adoption of modern technology, such as the internet and digital cameras, has revolutionised traditional trading methods over the past decade, making middlemen somewhat obsolete.

Other factors have also diminished Brazilian gem production, such as the evolution of the international market. Many African countries now produce a larger variety and quantity of gems than they did a couple of decades ago, and those stones are usually sold at lower prices than those from Brazil. The high cost of mining is another reason for the recent decline in mining and production. According to the DNPM, there were 2,294 gem occurrences in 401 different municipalities as of 2013, with 49.3% of them in Minas Gerais and 19% in Rio Grande do Sul.

What about Santa Maria Aquamarine?

One of the rarest and most expensive varieties of aquamarine, the “Santa Maria,” has a deeply saturated blue color with no hint of green or yellow. Named in honour of Santa Maria de Itabira, where these stones were first discovered, the original deposit is now almost depleted, and today most of the Santa Maria colors are also found in several sub-Saharan countries of Africa, including Mozambique.

The coloring process is due to the Fe2+ – Fe3+ charge transfer. This feature is associated with intense absorption and strong pleochroism, and this process cannot be induced by heat treatment. The stones are nearly colorless in the direction of the optic axis and intense dark blue perpendicular to the optic axis.

Figure 4: This 22.93 ct aquamarine is from Santa Maria in Minas Gerais. Courtesy of Paul Wild; photo by Jordan Wilkins.

Quartz and Topaz from Brazil

Quartzes are abundant in Brazil. Stunning crystal clusters, appreciated by collectors, come from hydrothermal veins found in the Curvelo and Corinto areas of Minas Gerais. Rose quartz is found in pegmatites in the northeastern part of Minas Gerais, while rutilated quartz has been produced mainly in the Novo Horizonte District of Bahia State.

Huge amethyst geodes and most of the agates of the country have been mined in abundance in Rio Grande do Sul. Citrine is also mined there, but most of the citrine produced and exported from Brazil is heat-treated amethyst.

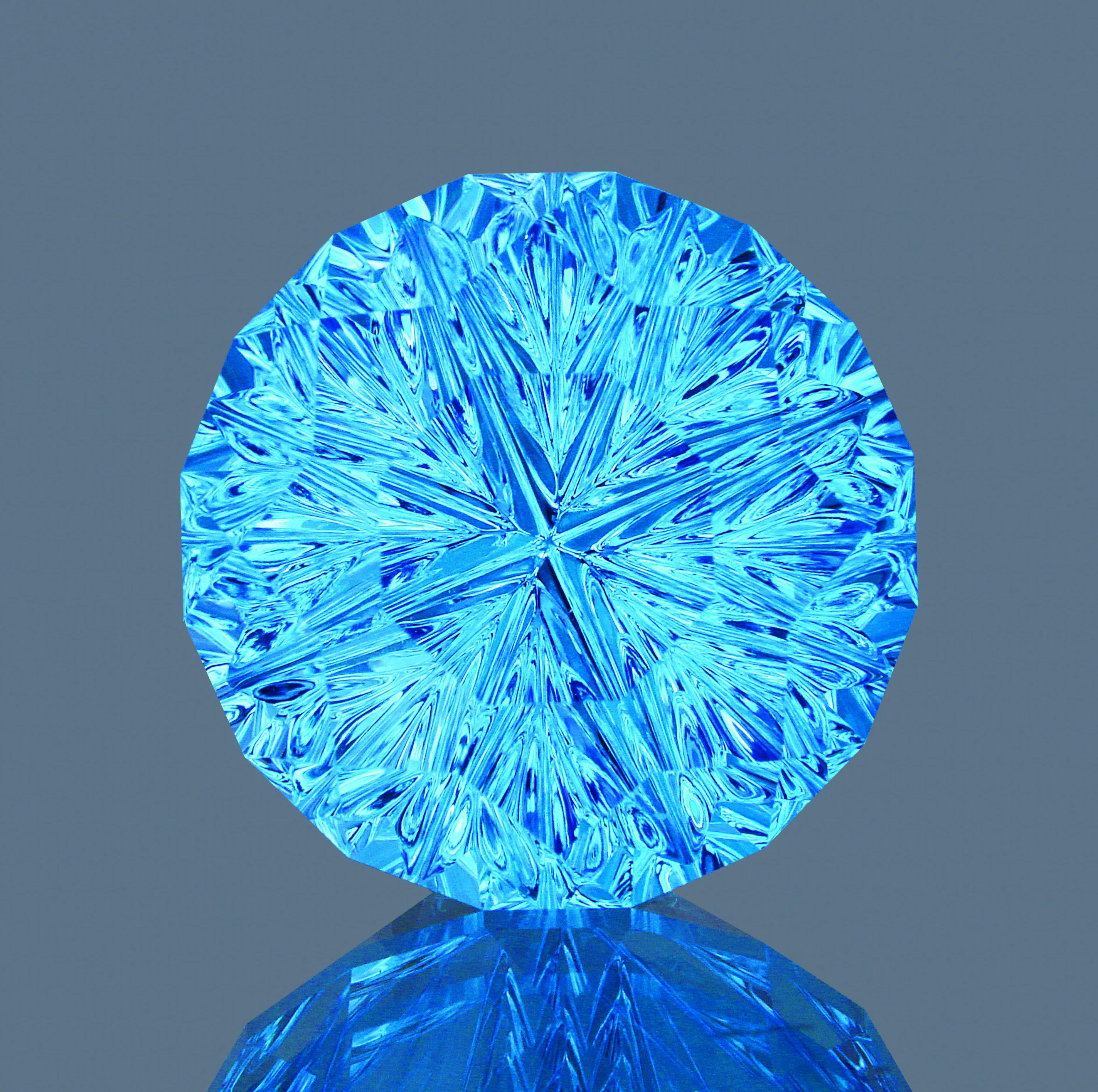

The country accounts for much of the world’s topaz production. Many stones are colorless or tinged very light blue, and laboratory irradiation creates a bright blue color. A post-irradiation annealing is performed by a heat treatment of the topaz for several hours at around 200°C. However, the production of the rare and famous orange-to-orange-pink Imperial topaz has greatly diminished, and good-quality material is particularly scarce on the local market.

Figure 6: The color of this Swiss Blue topaz (13.73 ct, StarBrite cut) was produced by laboratory irradiation using colorless or pale blue starting material from Brazil. Courtesy of John Dyer; photo by Ozzie Campos.

More Gemstones of Brazil

Beryl production is dominated by light to medium-dark blue aquamarine, of which Brazil may be one of the largest exporters, with other beryls including heliodor and morganite. Most chrysoberyl production is still located in Minas Gerais and Bahiam, but good quality Alexandrite is now harder to find locally, and only small quantities are available. Collectively, Emeralds and other beryls, tourmaline, topaz, and all types of quartz are the most widely mined colored stone resources nationwide.

What’s Next for the Brazilian Gemstone Industry?

Improved living conditions in rural areas have led to an evolution of the workforce, which is becoming less interested in and less reliant upon mining via illicit operations. Brazilian gem exports remain robust, and gem mining is shifting toward bigger and more professional companies.

The quantity of mining areas remains substantial and, probably, to a large extent, underexplored. Yet, the future of the Brazilian gem industry may depend more on social issues, global market trends, and the ability to establish efficient trade relationships.

Source: Gemmological Association of Great Britain, www.gem-a.com. This is a summary of an article that originally appeared in The Journal of Gemmology entitled ‘‘Coloured Stone Mining and Trade in Brazil: A Brief History and Current Status’ by Aurélien Reys 2017/Volume 35/ No. 8 pp. 708-726. Featured photo: This large colour-zoned tourmaline from Brazil weighs 144.75 ct. Courtesy of Paul Wild; photo by Jordan Wilkins.