Understanding Gemstone Origin

Some gemstone species only have a single point of origin, while some gem types are limited to a specific commercial locality that determines their value and desirability. Others are linked to certain locations to increase their importance or achieve a higher price. Here, Gem-A Gemmology Tutor Pat Daly FGA explores the connections between gemstones and their global locations, including tanzanite, charoite and jadeite, to name a few.

Most minerals and gemstones are named for their properties or after people and places. The mineral kyanite, for example, is named because it is commonly blue (cyan). Liddicoatite (tourmaline), taaffeite and painite, on the other hand, are named after those who were closely connected to their discovery.

Gemstones with Just One Commercial Locality

Many species and varieties are named after the places where they were first discovered. Andalusite, for example, was named because the first samples of the stone which were studied came from Andalusia, Spain. The green grossular garnet variety tsavorite was named after the Tsavo National Park in Kenya, where it was first mined. It has been found elsewhere, but most good quality stones are still found in the mine from which it was first recovered.

Charoite in the Gem-A Gemstone & Minerals Collection. Photographed by Henry Mesa.

Charoite is an opaque, purple rock with a distinctive and beautiful silky texture which is unique among gemstones. It was discovered in Siberia in about 1940 and was named after the Chara River, but it did not appear on the world stage until the 1970s. It is an example of a gemstone with only one commercial locality.

The lovely blue stone benitoite was discovered in 1907 in San Benito County, California. It has been found elsewhere, in small amounts, but gemstones have only been mined from the small area where it was first found. Gem quality Brazilianite, a transparent yellow gem mineral originally described in 1945, is recovered from a few mines in Brazil. Like benitoite, it has been found in other localities, but they rarely produce gem-quality stones.

Brazilianite from the Gem-A Archives. Photographed by Henry Mesa.

Gem Varieties with Limited Sources

Gem varieties with limited sources are more common than species. Blue John, a purple and white to yellowish-banded variety of fluorite, is only found in the Castleton area of Derbyshire in the UK. It has been mined since the 18th century and was popular for a hundred years or so, with fine ornaments from this period displayed in many stately homes.

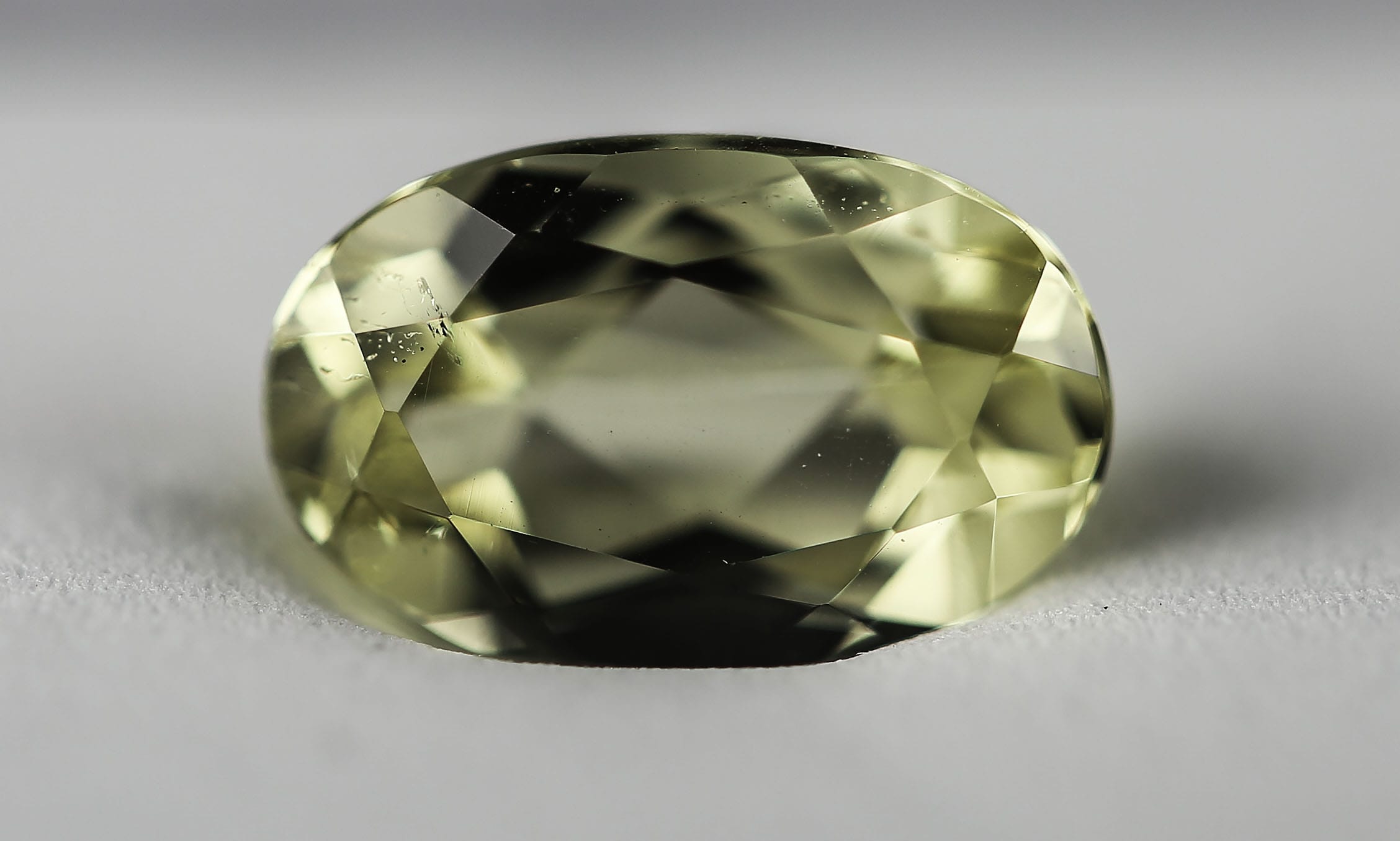

Tanzanite, the blue to purple gem variety of the mineral zoisite, is mined only in Tanzania. Moldavite, the transparent green glass produced by a meteorite impact, is named after the Moldau (Vltava) River in the Czech Republic, and most stones are found in the south of that country.

Tanzanite cabochon. Photographed by Henry Mesa.

The occurrence of many important gem species is limited. Jadeite, for example, may be found in Guatemala, Italy and Russia, but they are outstripped in commercial importance by Myanmar, from which almost all valuable jade is exported.

The Influence of Gemstone Localities on Value

Locality names may be important selling points for some gemstones because, in the minds of traders and consumers, they have become associated with stones of high quality. Colombian emeralds and Burmese (Myanmar) rubies acquired this reputation, and Kashmir is the almost legendary source of some of the finest blue sapphires the jewellery trade has seen. Such associations may be misleading, however, because not all stones from these localities are of the best qualities; stones of equally good quality are available from other localities, and, in the case of Kashmir, the deposits yield few stones today.

Colombia is still a major source of emeralds and high-quality stones are available in gem markets, but Zambia, another major producer, also supplies fine specimens. Gemmologists and jewellers have said many times that what matters is the quality of a stone rather than its geographical source.

Close-up view of a ruby crystal. Photograph from the Gem-A Archives.

The East African country of Mozambique is now the main producer of fine rubies in the gem trade, and the best examples are comparable to those of Myanmar. They are similar in origin, and there are many resemblances between stones from the two sources, so laboratory tests may be needed to distinguish them.

Top quality blue sapphires from Kashmir contain fine, milky-looking inclusions which give the stones what has been called a velvety appearance. These stones, which were mined only during the 1880s, are rare and valuable. Later finds from the same locality have not matched those which were first mined, but similar-looking stones have been found more recently in Madagascar. Their appearance may rival the Kashmir stones and some of them have been claimed to come from that source. This circumstance illustrates a common tactic employed by some traders of claiming a well-known traditional source for stones from a more recent locality.

The Historic Ties Between Gemstones and Their Point of Origin

Until about 1725, diamonds were imported to Europe from India and Borneo, the only known sources up to then. Stories were circulated that diamonds from Brazil, which entered the market at that time, were of poor quality and, it is said, traders would export the stones to India before sending them on to Europe to obtain higher prices. Stones of several types and localities have been traded in a similar way by disguising their sources and claiming that they came from elsewhere.

Gemmological laboratories now take great care to analyse the properties and chemistries of important gemstones so that they are able in most, but not all cases, to offer a professional opinion on the sources of emeralds, rubies, sapphires and alexandrites.

In principle, it should be possible to do the same for many gem varieties, but the costs of establishing reliable databases are high, and so is the cost of buying and using the scientific instruments used to obtain the information which is needed.

The Provenance of Paraiba Tourmaline

Another stone whose value may justify the costs of establishing its provenance is Paraiba tourmaline. In the 1980s, vivid blue to green stones were found in the Brazilian state of Paraiba. Their unusual and highly desirable colour has been attributed to traces of copper and manganese, and it raised the value of this variety far above the general prices paid for good quality tourmalines.

Bulgari Colour Journeys Paraiba Tourmaline High Jewellery necklace in pink gold with seven cushion-cut Paraiba tourmalines of 36.81 carats. Photo courtesy of KaterinaPerez.com.

Stones of similar colour were discovered in another state in Brazil, Nigeria and in Mozambique. Although the colours of all these stones may be similar, those from Paraiba have tended to fetch higher prices, and buyers may pay a premium for them.

Conclusion

Locality names associated with gemstones should be approached with care. The term Paraiba tourmaline may refer to a stone from Paraiba or another mining location for that variety. Hence, it should be named Paraiba-like tourmaline! The terms Kashmir sapphire and Australian opal may be accurate statements, but some terms are misleading. The name Cairngorm has been used for smoky quartz, regardless of its source, and Siberian amethyst is likely to refer to its perceived quality rather than the locality of a stone.

Other names may be wholly misleading. A geographical name preceding diamond usually means quartz or some other white stone. There are dozens of such names, including “Bristol diamonds”, “Cornish diamonds”, “Irish diamonds” and the well-known “Herkimer diamonds”, from New York state in the USA. The names of many other gemstones have been similarly abused.

When purchasing gemstones that claim to be from coveted international sources, be prepared to ask questions and be sceptical until reputable laboratory reports are provided.

Source: The Gemmological Association of Great Britain, www.gem-a.com