The History of Golconda Diamonds

Renowned jewelry historian and published author, Jack Ogden FGA, traces the history of Indian diamonds and questions the sustained marketing hype around the famous Golconda mines.

Today India is the largest centre for diamond cutting, handling some 90 percent of the world’s diamonds. But most who cut, sell or buy these diamonds, in the cutting centre of Surat or at the vast diamond exchange in Mumbai, are probably unaware that in the past the country was also the world’s major source of diamonds.

Exceptions are the dealers in larger stones, ones they hope a laboratory report might link to the famous Golconda mines in India, a link that allows a price premium.This article will look at India’s remarkable diamond history and ponder whether associating a diamond on the market with ‘Golconda’ is really just marketing hype.

Diamonds from India

Before the discovery of diamonds in Brazil in the 1720s, most came from India, a few from Borneo. The ring in figure 1 was made two thousand years before the Brazilian discoveries by a Greek goldsmith who had travelled as far as what is now Aï Khanoum in the extreme north of Afghanistan, a city founded in the wake of Alexander the Great’s conquests. A pink sapphire, almost certainly from Sri Lanka, is flanked by two small diamond crystals. Found in 1999, it is the earliest surviving diamond ring from an archaeological excavation.

Figure 1: A pink sapphire and diamond ring, crafted by a Greek goldsmith, two thousand years before the discovery of diamonds in Brazil in the 1720s. It is the earliest surviving diamond ring from an archaeological excavation. Photo credit: Osmund Bopearachchi.

This early jewelry use of diamonds had been preceded by diamond chips used to drill and engrave other gemstones. The hardness that made them so useful here also led to their use as gems. Rough diamond crystals are hardly pretty, but they were a perfect symbol for strength.

Indeed, our word ‘diamond’ derives from the Greek for ‘invincible’. Diamond-set jewelry only appeared in the countries around the Mediterranean a few centuries later than they had further east. The ring in figure 2 dates to about 300–350 AD and was found in Syria, then under Roman rule and strategic in the trade in luxury goods from India and the East.

This ring is set with an uncut brown diamond weighing about seven carats and is the largest diamond surviving from the ancient world.

Figure 2: Dating to about 300-350 AD, this ring is set with an uncut brown diamond weighing about seven carats and is the largest diamond surviving from the ancient world. Photo credit: Jack Ogden.

Diamonds in Medieval Jewelry

With the fall of the Roman Empire, trade with India fell off and we find little evidence for diamond-set jewelry in Europe again much before the 1200s when the Eastern trade began to be re-established. A superb example of Medieval diamond-set jewelry from the mid to late 1300s is the Crown of Princess Blanche, also called the Bohemian or Palantine crown, now in the treasury of the Munich Residenz (3).

The crown left England as part of the dowry of Princess Blanche, daughter Henry IV, when she married Ludwig III in 1402. In addition to the wide range of colored gems it is set with, it also has just over thirty diamond crystals of which a quarter are imitation — as described in an original inventory.

These diamonds and the other gems in this crown were discussed in detail by Karl Schmetzer and Albert Gilg in The Journal of Gemmology Vol. 37(1). Whether the ‘invincibility’ of diamond was associated in Europe with a hoped for constancy in love by the time the crown was made is uncertain, but this link had certainly appeared by a few generations later.

It was not an invention of De Beers. A diamond and ruby ring specifically described as a marriage ring is listed in the will of an English woman written in 1505. This was quite probably like that in figure 4, of which several examples are known. This particular one, from the late 1400s, was found near Launde Abbey in Leicestershire, England, in 2013 and later sold at Sotheby’s.

Figure 3: The Crown of Princess Blanche, also called the Bohemian or Palantine crown, from the mid- to late-1300s. Photo credit: Jack Ogden.

Perhaps here the diamond represented the unbreakable nature of marriage, the ruby a wish for fertility (red gems had long had such an association).

Unlike those in Blanche’s crown, the diamond here is polished. Very rudimentary cutting and polishing of diamonds had become possible by the later 1200s and during the 1400s improved machinery provided the rapid, even rotation necessary for the development of more sophisticated cutting.

Figure 4: A diamond and ruby marriage ring from the late 1400s, found near Launde Abbey in Leicestershire, England, in 2013 and later sold at Sotheby’s. Photo credit: Sotheby’s, London.

The Early Days of the Indian Diamond Trade

Seven years before that English woman had written her will, the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama had stepped onto Indian soil following the first direct sea voyage from Europe. Sea trade with India and the spice lands of the East Indies began to blossom. The English and Dutch wrestled this trade from Portuguese hands and the English East India Company became a major player in the Indian diamond trade.

There were rich diamond mines in India and huge treasures of diamonds amassed by the local rulers over the previous centuries. William Hawkins who was with the East India Company in India in the early 1600s, estimated that the treasury of the Mughal emperor Jahangir at Agra included more than 135,000 carats of uncut diamonds, with none under two and a half carats.

Our knowledge of the localities and working of the Indian diamond mines are largely derived from the accounts of traders coming to India from medieval times onwards. Early Indian texts sometimes list diamond sources, but it is seldom possible to identify these with modern places names.

The earliest Indian diamond mines were likely those in the north of India, with two mining areas further south coming later. One of these was Golconda. The name Golconda can refer to a city, the region of which it was capital, or to a particular diamond mining area. This area is shown in the map of 1744 in figure 5.

Golconda Diamonds: Dispelling the Myths

Golconda, essentially modern Hyderabad, was an important centre for trading diamonds from local and other mining areas. The ‘Golconda’ diamond mines are usually accepted to be those from the south-east, between the city and the sea, primarily along the Krishna river. However, these Golconda mines are almost certainly not the ‘legendary’ source of diamonds in early times, nor the oldest source in the world, as is often asserted.

Figure 5: The area of ‘Golconda’ shown in a map from 1744. Photo credit: antiqueprints.com.

Reports from East Indian Company personnel, Dutch diamond merchants and others make it clear that the famous Golconda mine at Kollur (shown as Coulour on the old map in figure 5) was the first mine found in this area and that was not until around 1619.

The area quickly began to produce a large number of diamonds, often of good sizes. William Methwold, an administrator with the East Company noted that “jewelers of all the neighboring nations resorted to the place” and that there were 30,000 working there.

But there was still a huge amount of diamond mining going on elsewhere in India and the 130,000 carats that Jahangir had amassed in his treasury had been found before these Golconda mines had been discovered. An older, and still very productive, diamond mining area further west did technically become part of the Kingdom of Golconda in 1564, but these mines were always clearly distinguished from the famous ‘Golconda mines’ in past descriptions by diamond merchants, geographers or other observers.

The Golconda Reputation

After the 1720s the importance of Indian diamonds was eclipsed by the discovery of diamonds in Brazil, and a century and a half later by those from Africa. The importance of the Golconda mines to the East India Company’s trade in the 1600s had made the name a household one in England and it has continued to resonate since, leading ultimately to the almost mythical status apportioned to ‘Golconda’ for diamond marketing purposes. To save embarrassing modern auction houses, I will show an older example.

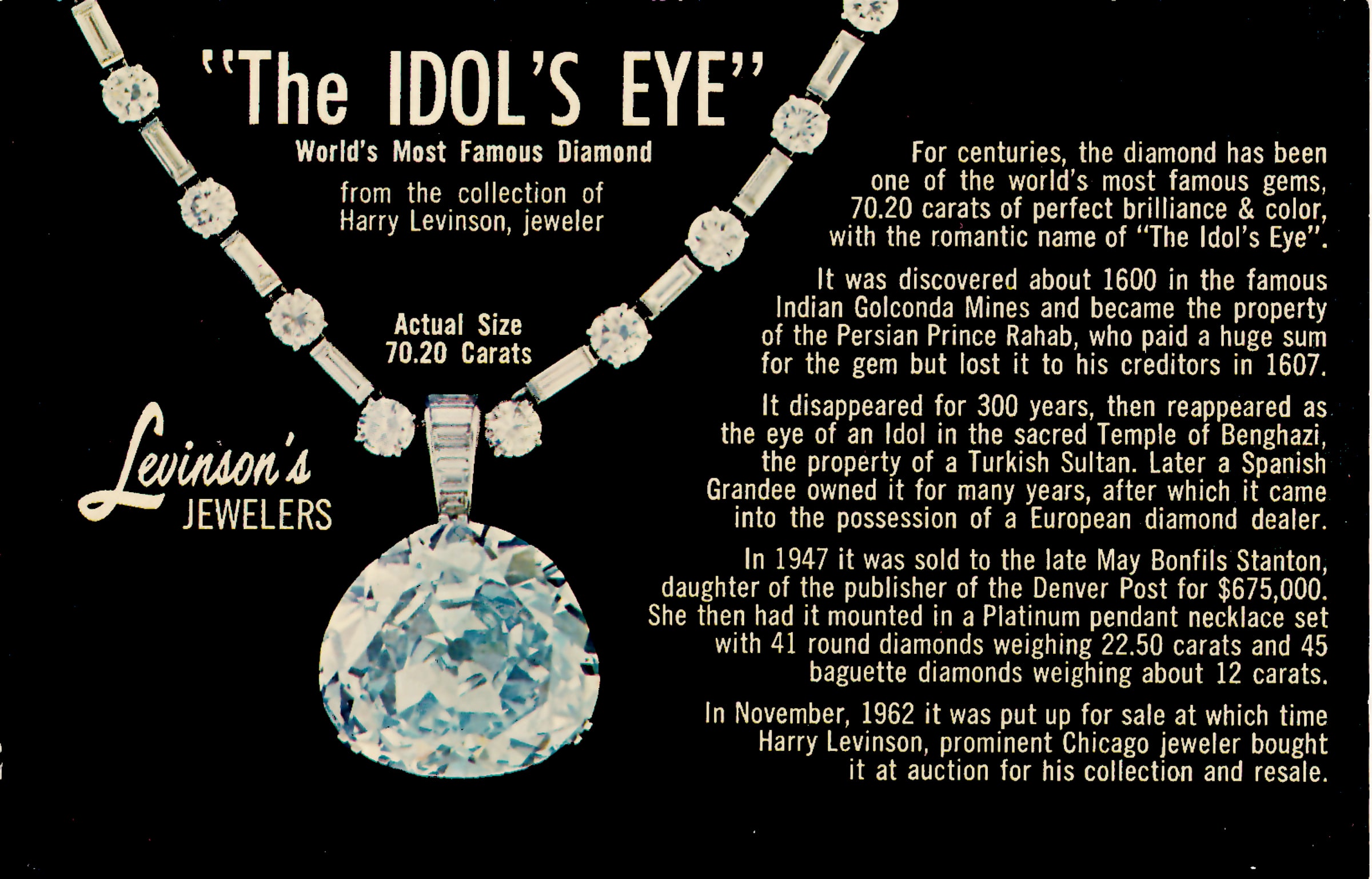

The advertisement in figure 6 is from Harry Levinson of Levinson’s Jewelers Inc in Chicago from the late 1960s or early 1970s. The blue Idol’s Eye diamond is almost certainly from India, but there is no evidence whatsoever to support the assertion that, “It was discovered about 1600 in the famous Indian Golconda Mines” let alone that it had once belonged to an otherwise unknown “Persian Prince Rahab”.

Figure 6: An advert from Harry Levinson of Levinson’s Jewelers Inc in Chicago from the late 1960s or early 1970s, showcasing the blue Idol’s Eye diamond, which is almost certainly from India. Image from a private collection.

These statements had first been made when the stone sold at auction in New York in 1962. Things have become slightly more objective since then and laboratories tend to apply the term ‘Golconda type’, if they use it at all, only to large Type IIa diamonds of exceptional color and clarity. But to my knowledge there is no evidence that top quality Type IIa diamonds were more prevalent in the Golconda mines than at others in India.

Diamonds have a remarkable history in which India plays an important part, including the renowned mines of Golconda. This should be celebrated. But am I alone in thinking that it is unfair to the ultimate buyers to use ‘Golconda’ like a brand name to boost profits with seemingly little concern for historical accuracy or scientific justification?

For more on the early history of diamonds see Jack Ogden’s Diamonds: An early History of the King of Gems (Yale University Press 1918).

Source: The Gemmological Association of Great Britain, www.gem-a.com, The full version of this article was first published in the Autumn 2020 edition of Gems & Jewellery, Vol. 29 (3).