The Geology of Diamonds

From the Spring 2018 issue of Gems&Jewellery magazine, Gem-A assistant tutor Beth West FGA DGA explores the remarkably epic journey of diamonds and how their characteristic strength is rooted in their archaic origins.

“In the deep glens where they lived all things were older than man and they hummed of mystery.”

Cormac McCarthy, The Road

Carbon is the fourth most abundant element in the universe. It is one of life’s most important building blocks. We are made up of around 18% carbon. The diamond, however, is formed of pure carbon and bonded in such a way as to make it the earth’s hardest naturally occurring substance.

But these magnificent gems extend far beyond their beauty and durability; they carry whispers of the beginnings of our world.

How old is a diamond?

It has been proven that the oldest diamonds formed around 3.5 billion years ago in an age known as the Archean Eon. At this point, it is believed that the planet had only existed for around 1 billion years. The surface of the earth was still settling.

How are they formed?

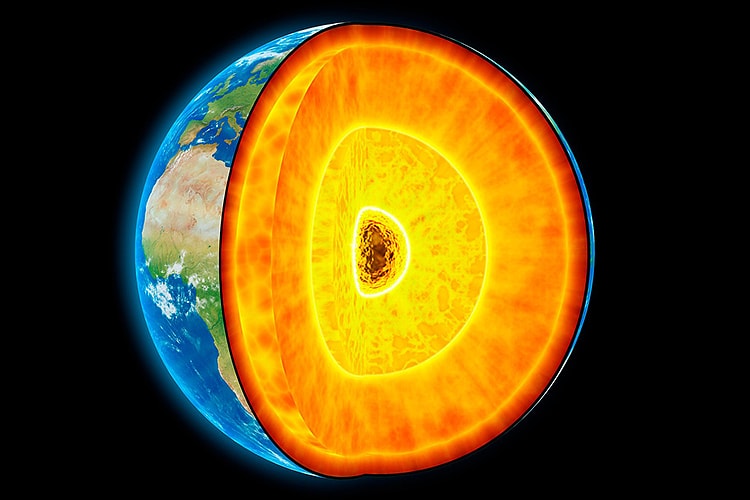

The earth is formed in layers. The outer most layer is known as the crust and ranges between 6km and 40km deep. It is divided into the thicker continental crust, making up the landmass, and oceanic crust – the ocean floors. Beneath the crust is the mantle. It accounts for eight tenths of the earth’s volume and is predominantly composed of an igneous rock known as peridotite.

The upper most portion of the mantle and the crust are known as the lithosphere (‘rocky sphere’ in Greek). This part of the earth is rigid, whereas the deeper parts of the mantle are in a permanent state of convection as the rock melts and cools. At the centre of the earth, the liquid core encases the solid inner core – the 5500° C iron and nickel heart.

In the Archean Eon, as the crust shifted and split, portions of it found their place and settled. These archaic, unmoving pieces of crust are known as ‘cratons’. Under each craton is a root or keel of lithospheric mantle that can descend up to 300 kilometres deep. These keels are cooler than the neighbouring convecting mantle, at around 1200° C at its deeper points.

Diamond will start to form at around that temperature if the corresponding pressure is around 40000 atmospheres. That equates to a depth of around 140km. These deep lithospheric keels beneath the cratons, away from the chaos of the convecting mantle, were perfect safe-houses for a growing diamond.

Petra Diamonds’ South African Mine, Finsch. Showing open put with subsequent block cave extraction, tunnels visible.

Image by Charles Evans FGA DGA.

Where did the carbon come from?

The carbon would have derived from either a primordial source (extant from the birth of the earth) or from material pulled into the mantle when the ocean floor was pushed beneath colliding continental crust.

The carbon would have been locked into compounds such as methane (CH4) or carbonates (CO3) travelling in melts or fluids around the convecting mantle. When these fluids passed through the mantle keel, they would have reacted to the peridotite, freeing the carbon from their compounds and allowing it to crystallise as diamond. It is in these deep portions of the keel that the oldest diamonds formed.

How did they get to us?

They resided in the keel for millions of years until, around the age of the dinosaurs (between an approximate age of 300 and 80 million years old), they were expelled from their plutonic residence via forceful, violent eruptions of magma produced deep in the mantle.

Kimberlite is the most abundant of the three types of known diamond bearing magma. This powerful magma blasted through to the surface producing a cone shaped hole called a ‘pipe’. Those diamonds that were carried up with the blast were left shaken but intact in the magmatic debris that packed the hole or were forced to travel with the weathering surface of the earth – often for great distances, in rivers or in glaciers, and for millions of years.

From the depths of the earth to the ring on our fingers, these stones have certainly proved their strength. So when we are drenched by the sparkle and marketed bling of these gemstones, it is perhaps worth remembering their remarkable journey.

Source: Gemmological Association of Great Britain, www.gem-a.com. Diamond Crystal Image by Pat Daly.