Understanding Spinel

If you are new to gemmology, you may not be wholly familiar with the gem material known as spinel. Historically, these gems were confused with corundum, especially in red hues, which adds to its mystery and intrigue for gemmologists. Today, however, they are an important stone used in fine and high jewellery and deserve their own spotlight. Here, Gem-A tutor Pat Daly explores this important mineral in more detail.

The gem material we know as spinel is one of a group of minerals which share some features of their chemistry and crystal structure. They are oxides of magnesium, aluminium, iron, chromium, zinc and titanium, crystallizing in the cubic system.

What is the Composition of Spinel?

Almost all gem spinel is composed of magnesium, aluminium and oxygen, with most colours depending on trace amounts of the colouring elements chromium, iron and cobalt. Gahnite, zinc aluminium oxide, which is rarely of gem quality, is green to yellow, brown and black, and is rarely seen except as a collectors’ stone.

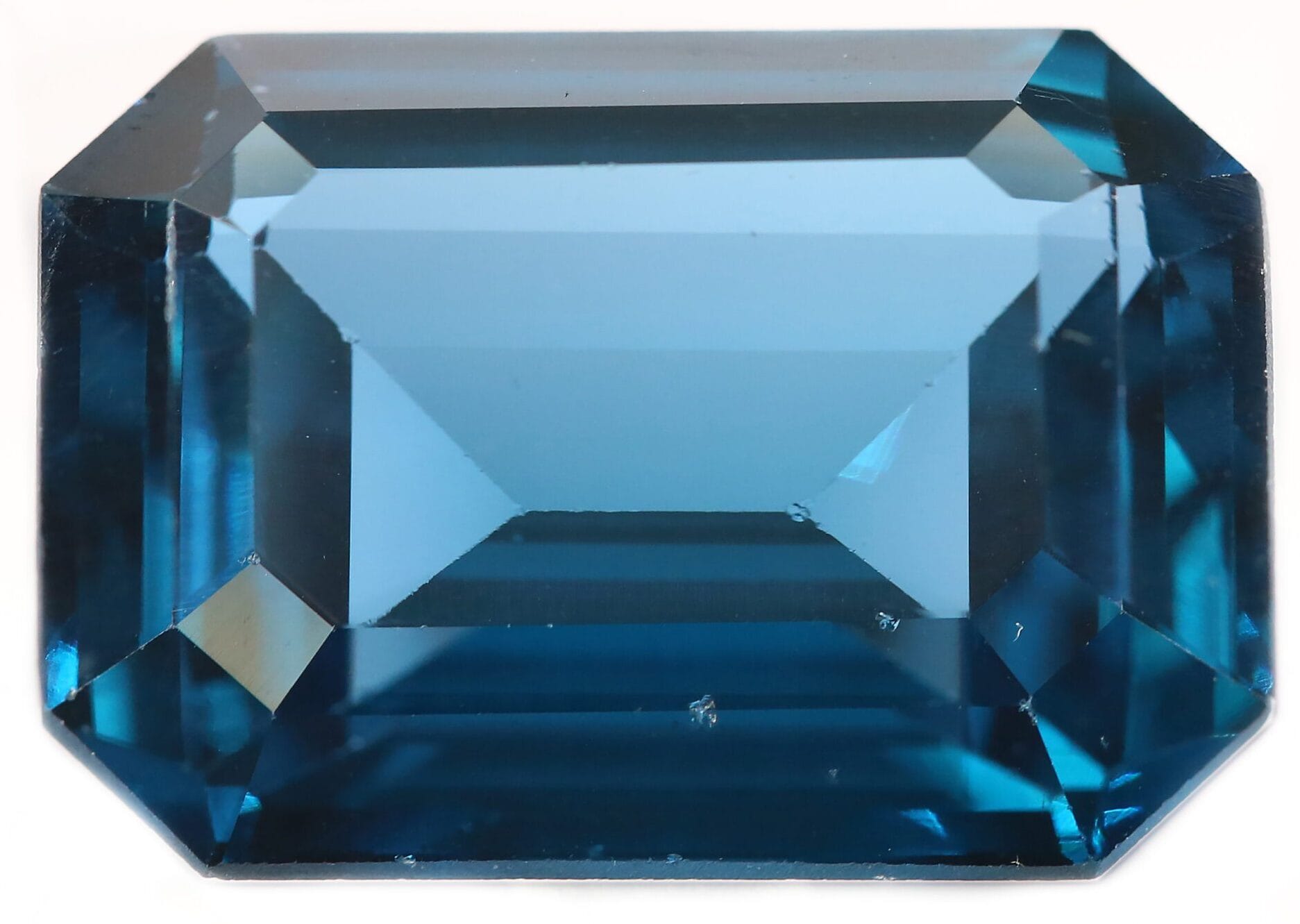

The characteristic lustre of a faceted spinel, photographed by Gabriel Kleinberg.

Crystals are octahedra, sometimes with minor faces replacing octahedral edges. Twinning is common, mostly of the same type which produces diamond macles. Crystals may twin in this way more than once, resulting in six-pointed star shaped twins. Twin planes may be seen within some fashioned spinels.

What Properties Set Spinel Apart?

Spinel is a durable gem material. Its hardness is eight on Mohs’ scale, and the absence of cleavage improves its toughness. It is resistant to strong chemicals, such as acids, and its colours do not fade.

An octahedral spinel crystal, photographed by Gabriel Kleinberg.

Spinel is isotropic, with an RI of about 1.717, but this may rise to about 1.740 in chromium-rich red stones and blue stones containing some zinc (gahnospinels). These optical properties make it easy to tell spinel apart from corundum, the species with which it is most likely to be confused on account of its appearance and occurrence. Red and blue stones have distinctive spectra which help to identify the gem variety and, in most cases, to separate natural from synthetic stones.

Where is Spinel Found?

Most gem spinel is found in marbles metamorphosed at high temperatures during continental collisions, such as in East Africa, Sri Lanka, and the Himalayan region, including Burma and Vietnam. Marble originated as limestone, essentially composed of calcium carbonate. Magnesium often replaces some calcium in limestones, and clay minerals mixed in the sediments supply aluminium; both elements must be present for spinel to grow.

A star spinel photographed by Pat Daly.

It has been suggested that all necessary elements were present in the rocks before they were changed by heat and pressure, and spinels are often accompanied by olivine (peridot, when of gem quality), diopside, corundum and other magnesium and aluminium-rich minerals. Gemstones are mined from the marbles or recovered from alluvial deposits after weathering and erosion of their host rocks.

What are the Common Inclusions in Spinel?

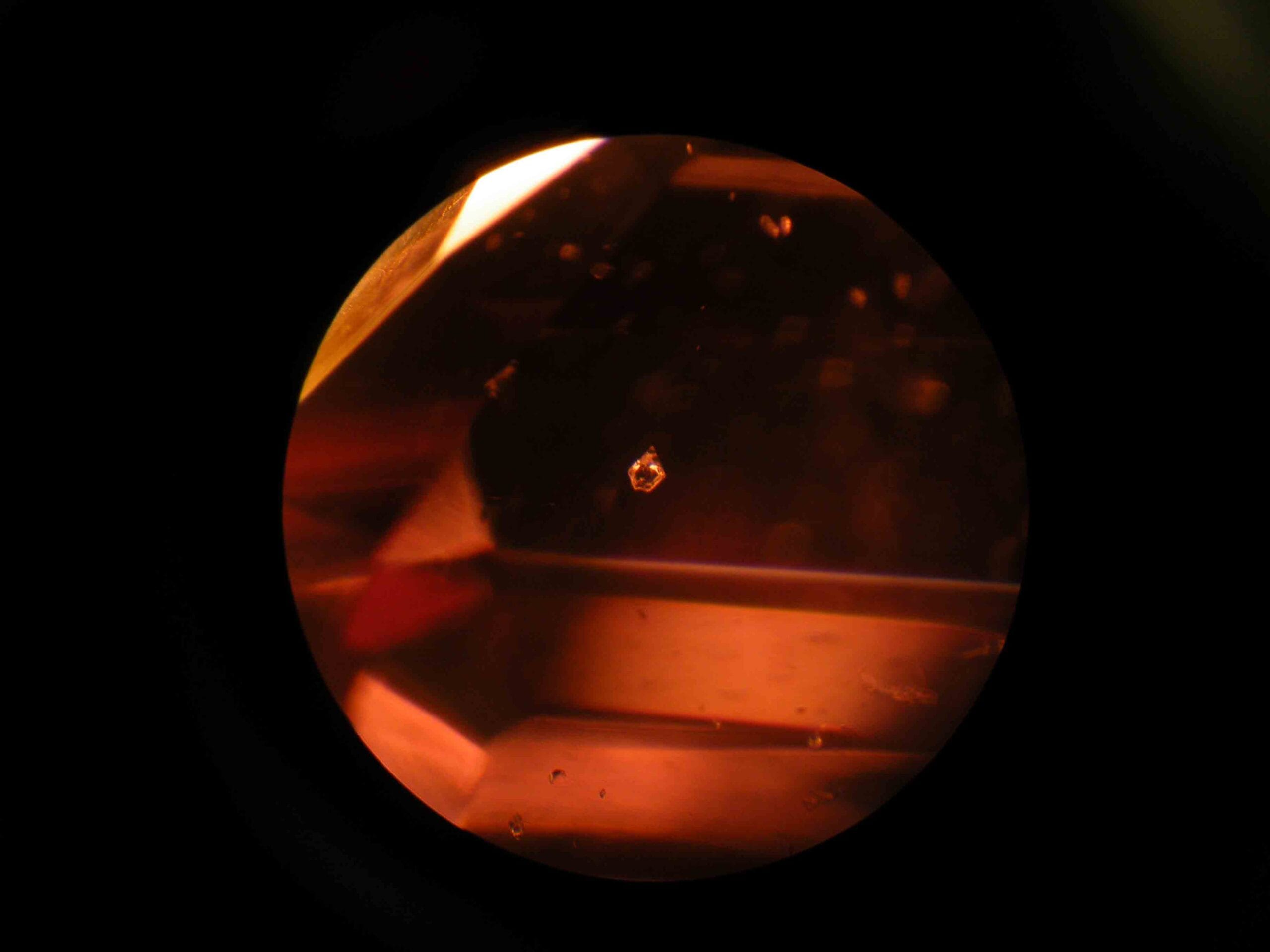

Inclusions in spinel may be minerals that were common in the rocks where they grew, such as olivine, hexagonal to rounded apatite crystals, graphite, and dolomite (calcium magnesium carbonate).

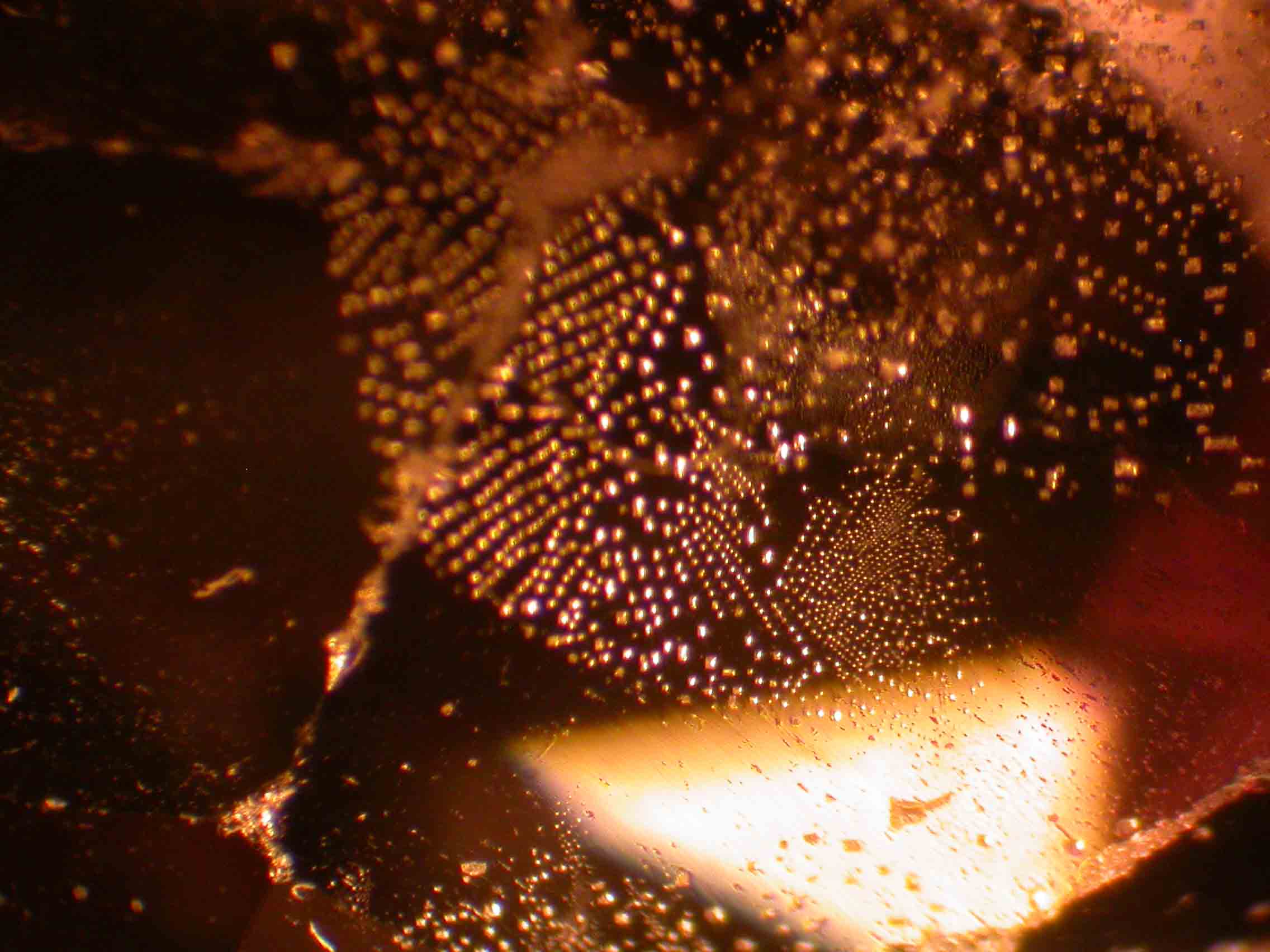

Feather inclusion in spinel, photographed by Pat Daly.

Needle-like or platy crystals, including rutile crystals, may cause four- or six-rayed asterism or, rarely, chatoyancy. Inclusions called zircon halos consist of crystals, which may be zircon, surrounded by radiating short fractures. In spinel, the crystals are usually of uraninite (uranium oxide).

Crystal inclusions may bear a close resemblance to those in corundum, but feathers of the type so often seen in corundum are relatively uncommon in spinel. Feathers in gemstones are thought to originate as fractures, which are partly healed before the stone has finished growing.

Feather inclusion in spinel, photographed by Gabriel Kleinberg.

They tend to look similar but there are some unusual types which help to identify gem species. In spinel, they are composed of lines of dozens of octahedral inclusions which give an overall neat appearance to the inclusion.

What Are the Key Colours of Spinel?

Spinel occurs in many hues and includes some very appealing colours, rivalling the appearance of corundum, which is famed especially for its vivid reds, pinks and blues.

Pink and red spinels owe their colours to chromium, as do pink sapphires and rubies, and, like them, the best colours are seen when they are modified by the least amount of iron. Unusually bright red stones have been called “Jedi spinels” because most others are a little on the dark side. Chromium activates fluorescence, and most red and pink spinels glow a bright red in long-wave ultraviolet. The ultraviolet in daylight may cause fluorescence, supercharging the body colour of the stone by adding emitted red light to its body colour; another phenomenon which it shares with some rubies.

A crystal inclusion in a spinel gemstone, photographed by Pat Daly.

Iron and cobalt are the main agents, colouring blue spinels. Most spinels mined in the past are coloured dominantly by iron and have rather subdued colours compared with sapphires. Because of this, they aroused little interest in the jewellery trade. In recent decades, several sources have produced stones which are coloured mostly by cobalt. They have intense, bright colours and are among the few stones which compare favourably with good-quality sapphires.

Why is Spinel Compared with Corundum?

The high RI and, consequently, the brilliance of well-cut spinels, as well as their colours, have made comparisons with corundum inevitable. In previous centuries, red spinels were often confused with rubies or thought to be a variant of them. Several famous historical “rubies”, such as the Black Prince’s Ruby in the Imperial State Crown, are unusually large red spinels. This comparison has been unfortunate in persuading many people to regard spinel as a substitute for corundum instead of a beautiful gemstone in its own right.

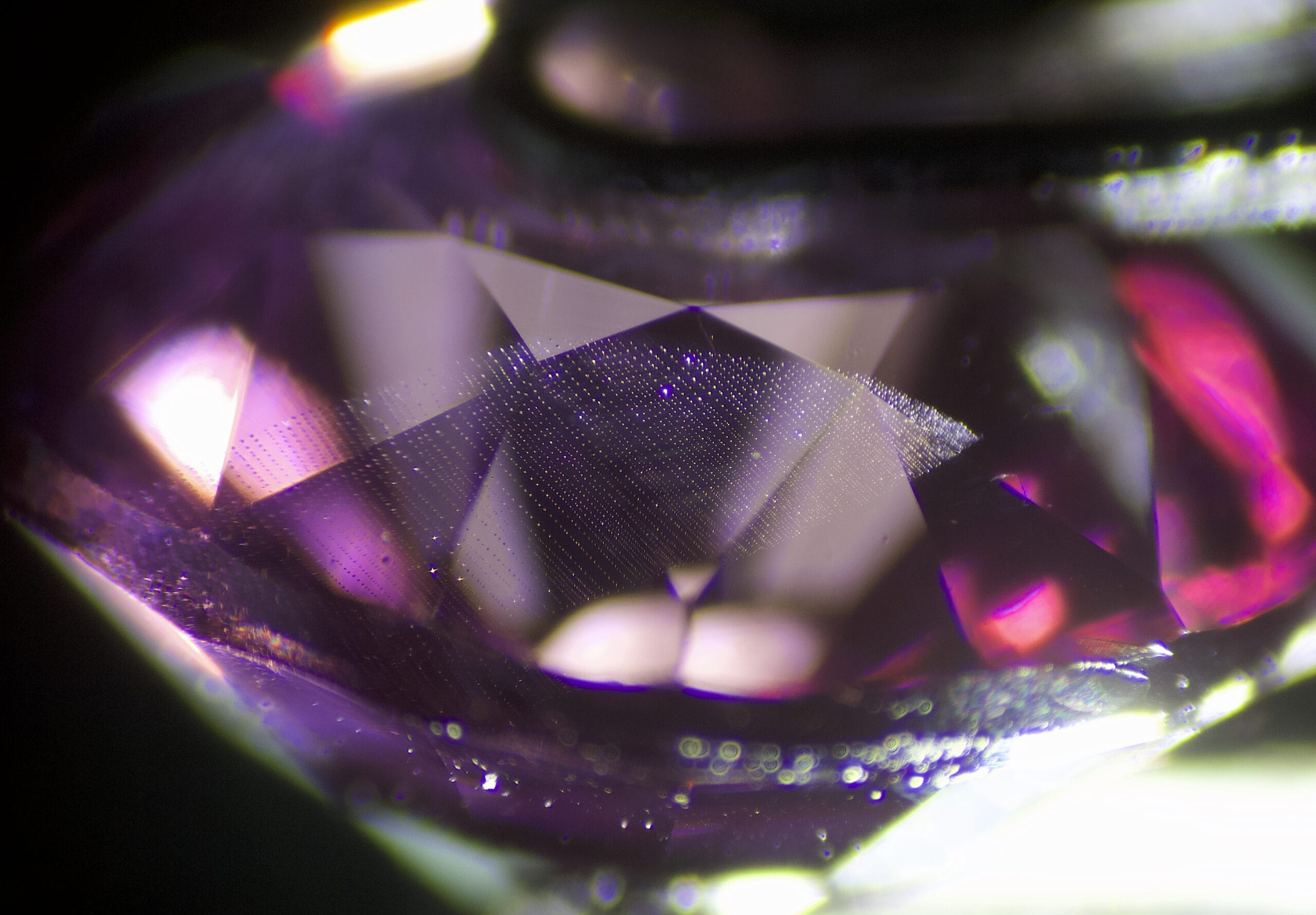

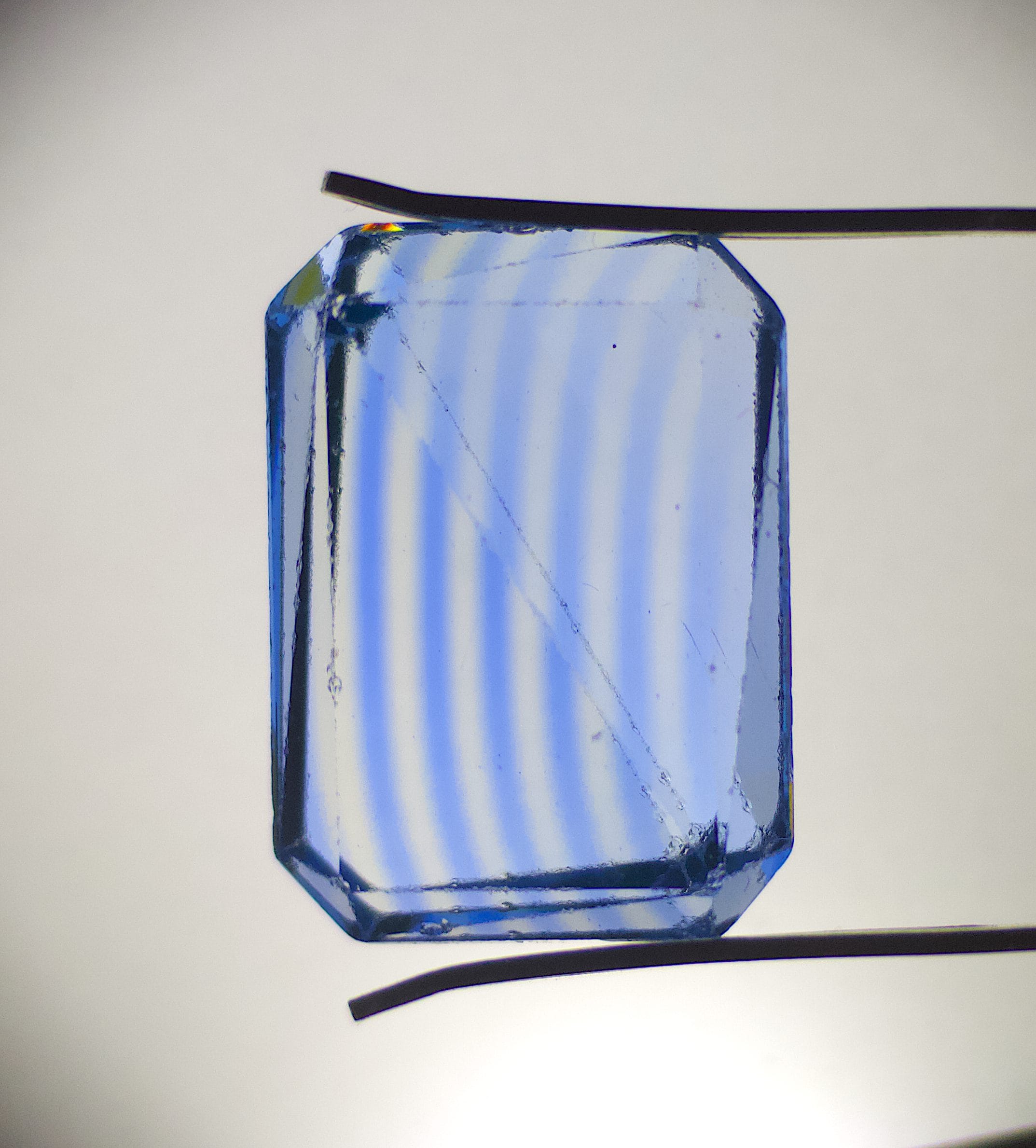

Synthetic spinel with curved colour zoning, photographed by Gabriel Kleinberg.

Combinations of red and blue provide a range of colours described as violet, lavender and purple. Orange and yellow spinels are uncommon, and white stones are rare and collectable, although they are seldom seen in jewellery. Grey stones, usually displaying faint blue or purplish hues, have aroused interest in the gem trade in recent years, and black spinel is easy to obtain.

Are Spinels Commonly Treated?

The colours of spinel are not often modified by heat treatment because the process seems to offer few benefits. Surface diffusion has been used, however, to drive the colouring elements cobalt and nickel a short distance into pre-cut stones. This is done to improve blue colours and, sometimes, to produce a green colour when nickel is used. These treatments are recognised by the concentration of colour related to the fashioning of the stone and evidence of high-temperature treatment.

Synthetic spinel photographed by Henry Mesa.

Synthetic spinel photographed by Henry Mesa.

Most synthetic spinels are made by the Verneuil process, almost always to simulate stones other than spinel, and their identification is straightforward. Flux-grown synthetic spinel is intended to substitute for spinel but may be separated from natural stones by inclusions of transparent brownish flux and, to some extent, by their spectra.

Spinel is a gem material which has been rather neglected, but which is now making a more favourable impression in the jewellery trade, and which is likely to appear more often in its products.

Source: The Gemmological Association of Great Britain or Gem-A. Top image: A blue spinel gemstone photographed by Henry Mesa.